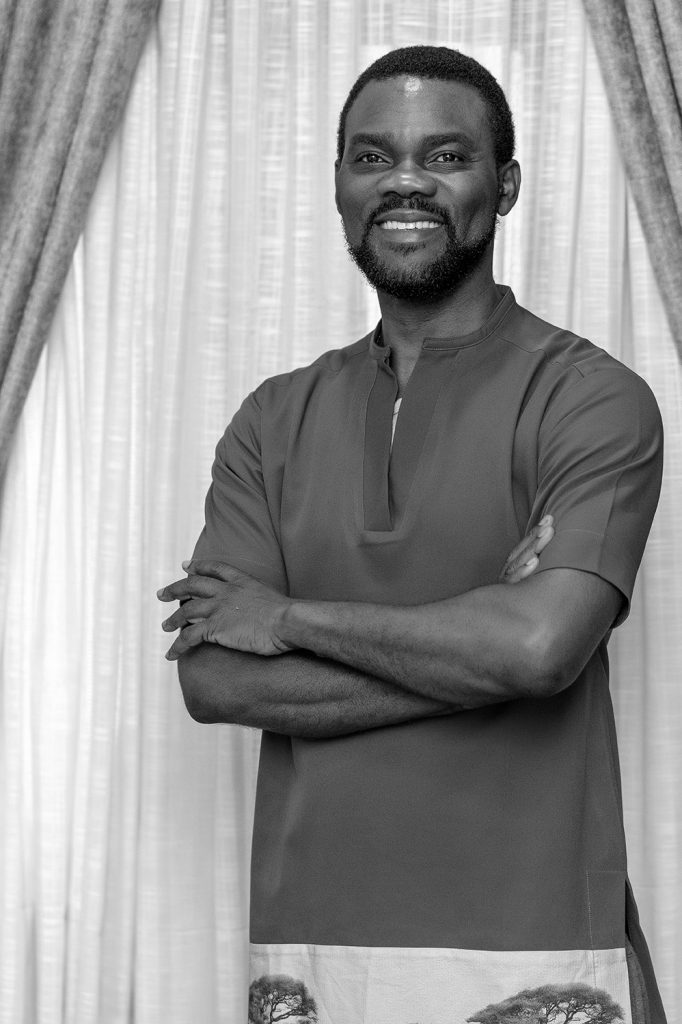

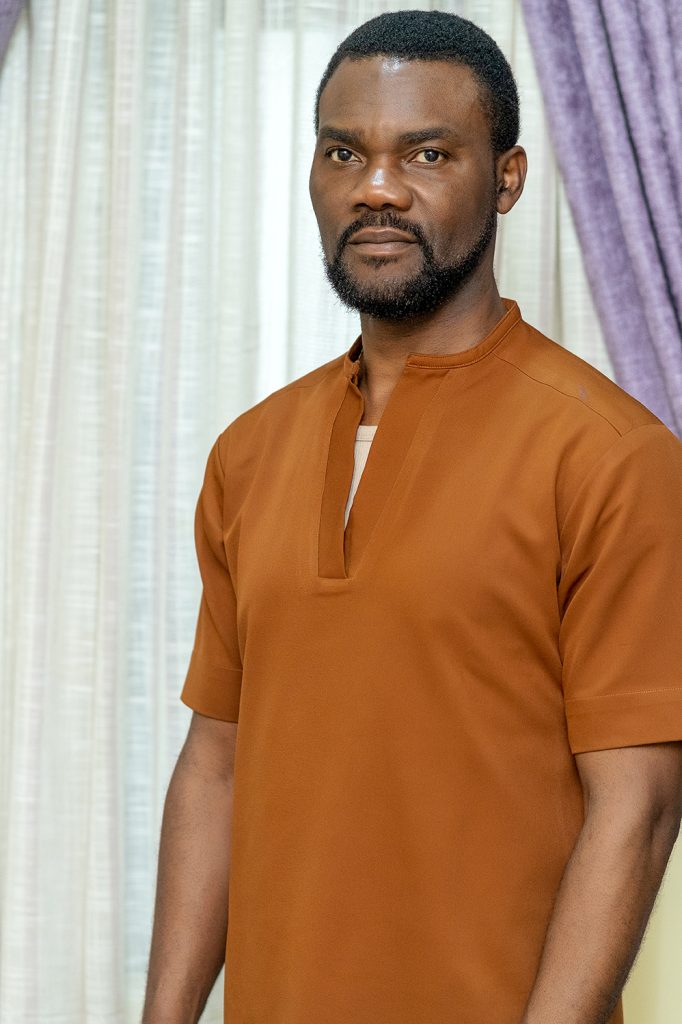

A Conversation With Enotie Ogbebor Art, Culture, And Inspiration

Enotie Ogbebor is a self-taught multidisciplinary artist, a visiting fellow to Cambridge University MAA, an Artist in residence at Cambridge University MAA, a Fellow of the prestigious DAAD, a Fellow, of the Society of Nigeria Artists, and the appointed Art and Cultural Consultant for the Edo State Government in Nigeria. His work revolves around painting, sculpture, music and performance, and so far, his work has proven to be a reflection of his lifelong commitment to creativity, culture, and heritage preservation.

In a candid conversation with TheWill DOWNTOWN’s Executive Editor, Onah Nwachukwu, Enotie Ogbebor explores the complexities of his art, the cultural influences that inspire his creative vision, and his distinct viewpoint on the significance of the returned artefacts.

You studied Economics and Statistics at the University, but your passion was art. Should people get a degree first before pursuing their passion?

No, I don’t think that should be a condition. It can be an advantage in that it broadens your mind. In my own case, because economics and statistics covers micro, macro economies, when it comes to economic activities on the micro or macro level, you learn to visualise things on a personal level, on a national level, on an international level, the volumes of trade, the types of activities required, the level of thinking, the depth of thinking, the search to achieve, the economic policies that govern individuals, companies, nations, and global production of goods and services, production and supply of goods and services. So you learn to look at how these decisions influence trade between individuals, communities, and nations, and how they impact politics, health, all aspects of life, defence, security, and so in starting my art practice, because of this training, I tend to look at my creativity from a point, apart from trying to achieve authentic expression, you also measure the impact of what you’re doing on individuals, on countries, on the world. So it gives you a perspective which is expanded, it’s bigger. So yes, it’s an advantage for me, but I would not say you have to do that. Of course, as an artist, you should be well-learned and broadminded.

However, I think research is a very strong part of my practice, and my art is my voice with which I contribute to various issues around the world. My practice focuses on cultural restitution, the rediscovery of our culture, which was dampened and diluted and, in most cases, cancelled by colonialism and the issues affecting our environment. As an artist, you draw a lot of inspiration from the environment, and for me, the indiscriminate felling of trees, the reduction of the natural habitat, which affects animals, birds, bees, and butterflies, which therefore reduces the beauty in this world, and endangers our lives as human beings generally, because we inhale oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide, and if you cut all the trees and cut all the plants, then how does this cycle continue?

It is like committing mass suicides –the way we are going about destroying our environment. The animals have their place in the cycle of life, facilitating this cycle of life and sustainability. If we get rid of all the animals as well, we are in trouble. So, I try to use my art to focus on these issues and to raise awareness and to also find solutions to be proactive. And then, of course, contemporary issues like human trafficking, illegal migration, all these issues, inequality amongst human beings, amongst races, amongst genders. For me, my art is like my voice, and any training I’ve received, any education I’ve received, contributes to how I carry out my research and how I tackle issues which appeal to me, which I feel are important for us as human beings.

Did you always know that you would end up as an artist?

Not really. I thought I was going to end up as an industrialist because of my family background. My father was an industrialist, and he has all these investments, which I’m sure he hoped I would grow into. But over the years, I’ve learned to combine my other responsibilities with my art practice without it affecting my career. Because the truth is, I never knew people could practice as artists and live in Nigeria.

Until I came across a childhood friend who had studied art, and I was like, ‘oh, okay.’ So, this really ignited my passion because I kept working as a hobby. I’m very passionate about it throughout my working career as a businessman and as an employee.

So what fueled your passion for the arts then?

Well, the thing is, I think I was born this way.

There’s this pressure that grows from inside to want to create, to be creatively expressive, so it’s something that has always pushed me from inside, from childhood. I always wanted to sketch and scribble things which I wanted to say, which I noticed or which appealed to me on my books, on my clothes, on my desk, on the chalkboard. I used to draw cartoons. It was just a continuous passion pushing me from inside.

And being fuelled by things I was experiencing all around me. And, of course, I was fortunate enough also to be exposed at an early age to some of the globally renowned sites like Egypt.

At the age of 10 or 11, my dad took me on a visit to Egypt, where I saw the wonders the Egyptians had wrought centuries ago. On a trip to Greece, where I saw the Parthenon, the Acropolis and all these things the Greeks had done centuries ago, we also visited Ethiopia, Kenya, and museums in Britain. So with all this exposure, I guess the question arose in me: What have we done in Africa? What have we achieved? And so, in that quest, which has now become lifelong, I was able to come to terms with the reality of colonialism and how the destruction and looting of our artefacts and our civilisation was systematically achieved. So, in wanting to learn more about my culture, the artefacts and the artworks we had at home took on new meaning.

The more I learned about the Benin bronzes, the ivory carvings, (samples of which we had grown up with in the house), it took on new meaning and sparked my curiosity. So, I started reading history on my own and reading about the various kings and their reigns in Benin. I started reading about Ife, Yoruba, Igbo, Boku, the Nok culture, among others. My mother is from Igun streets, which is the quarters for the famous Benin bronze casters, and so even growing up, going to visit uncles who used to play with their children, play with others and bronze casters while they were carrying out bronze casting, I mean, for me, I thought that was how everybody grew up.

You know, so all these experiences have been what have been pushing and fuelling this quest for creativity.

You were appointed as advisor on art and culture to the Edo State government. What are your thoughts on the returned artefacts?

Well, not all of them have been returned, but a substantial number held by the German museums have had their ownership signed over to Nigeria, and some have been returned, a small quantity.

The Smithsonian Institute Washington DC also returned all the Benin bronzes in their possession.

Cambridge University, Horniman Museum, etc., are all gearing up to return theirs, and I think this is a fantastic development, a good example of the quest to correct the wrongs of the past, the beginning. Like I always say, the return of objects is one thing, but the return of dignity, the return of knowledge, and the return of everything that has been lost, is something that we can never achieve, but we can strive to mend the gaps so that our people can come to terms with our history, with our heritage, with what we’ve done, with what our ancestors have done in the past. Because in defining development, you cannot define development as wholesome copying of somebody else’s achievements. Development really should be taking what your ancestors have bequest to you and taking it to a higher level, so that becomes development, but to copy somebody else’s work or culture or wholesale is not development. And so, we’re told we have no civilisation, we came from a background devoid of history, of achievements, but this is not true. So when our people see what our ancestors created, which are these, they’re not just mere artworks. A lot of them were created to keep our stories, to keep our history, a lot of them were created to keep our songs, our proverbs, and some were created for utility reasons, and some were created for religious reasons. So, in coming to terms with these objects and their relevance and their importance and what they were created for, we unlock a lot of our history, a lot of our knowledge, which our ancestors have discovered over centuries and which they have stored in these objects, in these concepts. Then, we ourselves will now discover the pedestal which has been created for us so that from there, we can climb upon it and continue to build, instead of trying to continuously dig foundations with the wrong implements which the colonial, unicultural administration or colonial concept had foisted on us. Now we can build, standing on the shoulders of our ancestors, who were giants in their own time, creating these masterpieces at the time when Europe was in the Dark Ages, at the time when Europe was in the Renaissance, at the time when Europe was flourishing. And so, we are also creating masterpieces, we are flourishing, we are our civilisation, we are our body of knowledge, we are our architecture, we are our language, our music, our poetry. And so, when we know all of this, then we can refine what we want, discard what we want, and, you know, contribute to the global cultural heritage and body of knowledge in an authentic manner, the way which bears the legacy of our ancestors and the tenacity and creativity of our people today.

What do you have to say to people who think we cannot preserve the artefacts that have been returned?

Well, first, they should realise that it is not by accident that these items are created from bronze, ivory, and wood, from materials which are unique materials like ivory, come from elephants, and those elephants are native to Africa, their origin is in Africa. Therefore, the weather, and the amount of care and attention we have to give to these artefacts are not at par when you take them to foreign places where the weather is extreme, between cold and hot. And so, we have to struggle to do all of that. But here, these items were already with us for over several hundred years before they were stolen, so they found them in pristine condition when they looted them. We had our traditional methods of preservation, and these artefacts were made to live around us. So, this argument that we cannot look after them does not stand in that sense because they are indigenous to us. Our weather favours them. I understand that yes, organisationally, we may not be at par in terms of our museum systems and all of that. But, in part of the argument that these works have become part of the global heritage. So, all hands must be on deck globally to preserve them. We are building modern institutions and storage facilities designed by world-class architects to also ensure that when these works are returned, they find a good place to stay.

They can be displayed according to best practice. But more importantly, we do not want to replicate the western concept of museums, in Benin city, where we are building MOWAA, the Museum of West African Arts, which was designed by the world-famous Sir David Adjaye, the concept is not to replicate the colonial construct of the museum because according to the colonial people, the museum was a place where items from conquered peoples were displayed. But, our museum is to reflect who we are. In Africa, we had no separate buildings as such called museums.

Our art was part of our lifestyle.

And therefore, our museums are being designed so that it is accessible to every strata of society. To everybody. It should be a centre where people can come and carry out activities and learn about their art, their heritage, and their history. And so, I don’t think that any of that has relevance as a viable argument. We can keep precious things in Nigeria. We keep diamonds, we keep gold, we keep precious stones. So, there’s enough awareness to ensure that they are properly kept and utilised.

In this digital age, how important is it for artists to introduce digital art into their work?

It’s very important to take advantage of the digital platform, because, in the first place, never in the history of mankind has a single market at large or a single platform ever been created.

Just imagine what it took for the Portuguese to sail on the ocean from Portugal to Benin to trade. Or what it took for Marco Polo to build their canals and harbours and ships to China or think about the turn of the century, the 19th century, when the state government discovered how they had to go three months, four months to go from Europe to America to trade and all of that, and today, you have the internet. With the internet, out of 8 billion people on earth, you have about 5 billion connected to the internet. So, it’s the single largest market ever created in the world. So, apart from just using digital tools for creativity, digital tools serve also as a platform for taking your works to the market, showcasing them to the world, for sharing your concepts with the world. So, you can imagine the 5 billion strong market. It would take forever to bring them into such a saturated market. So, we must not shy away from technology, in aiding our creativity, aiding our marketing, in showcasing our works.

Because now, a boy in a village in Nigeria can showcase his works to people in San Francisco, to people in Japan, to people in China, to people in America, to Canada. And we can have simultaneous results by being on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, or any of these platforms. And there are various online resources like galleries, online galleries, lots of galleries who are also art dealers, and all over who are on these platforms. Lots of art collectors and art enthusiasts are also on these platforms. You can sell your art as merchandise, I mean, endless possibilities.

Also, using digital tools to create artwork is becoming a norm. It’s part of the creativity, expanding the language of creativity. So, every artist must embrace research and experimentation so that you are not left behind.

You’re an authority in the Benin court arts. What does this entail?

Well, basically, as a result of the research I carried out, I started in 1995, when I was preparing to organise and showcase my works and the works of other artists in a travelling exhibition to commemorate the invasion of Benin in 1897. So, in 1997, there was a series of commemorative activities of which art exhibitions, which I was permitted to organise, was part of. And so, we carried out research and all of that. I realised that the bronzes, as beautiful and expressive as they are, did not capture the colours that you see when you go to cultural ceremonies, festivals, or functions in the Palace or elsewhere. The bronzes, ivory works, and the traditional Benin works could not capture the vibrancy; they don’t reflect the colours because of the materials. So, I decided to start creating a series of paintings that reflect the vibrancy of the events and to also study and research the underlying principles of the events from which this festival was organised so that this could be shared with everybody. And that is what I did. We got people to start studying history, the development of this festival, the origins of this festival, the meaning behind them, and all of that, to showcase and share. And so, yes, I was able to come up with the paintings which represent the different festivals and their relevance. So, we need to share these with the significance of the development of our culture, be it in music, in costumes, or in the processes. Yeah, this is what we started, and that’s why I began to do a lot of research to get everybody together and showcase them.

As a founder of Nosona Studios, what inspired you to use your studio as a training hub for children and younger artists?

So, as you know, Lagos is the guest hub for art in Nigeria.

Abuja is also developing at a fast pace, and Port Harcourt, but Lagos is the main hub, and all the art students, once they graduate, aspire to come to Lagos to try to get their head in. And, as you know, Lagos is tough, the economy is tough, so people tend to fall through the cracks and go to other things.

And so, I’ve always had the vision of sharing my spaces with artists. My first space was in Lagos in 1995. It was called Curio Studios. It was a huge space. I invited other artists to join to work on the collective. We trained IT students and all of that. I ran that for nine years. So, in 2016, when I came to Benin to get involved in politics and campaign for Government in Edo State, Godwin Obaseki I was able to get involved in those things. I tried to stay back in Benin and contribute to the development of the art and culture scene in Benin cities and other states. So, with this platform, students who are graduating from the University of Benin are going to be able to take a job in the government, and then the universities around could have a place where they could come and refine their practice, interact with older artists, get support to attend exhibitions, residencies, workshops, just to deepen their knowledge. And to help to create the value sector, every sector needs to be developed.

If you do not contribute to the development, you will be backwards, and you will be home-wrecked.

And one person can’t only be the sector; you have to be a collective. And, of course, as you share, you also learn. So, in Benin, it’s about the collective. It’s also a creative platform where younger artists could resign from their practice and they could come back with older artists. And there are also places where older artists can come and stay in the workshops and other residencies. And also create a platform where they can interact with international institutions. We have been partners to speak to Cape Green University, to SOA, to Oxford, to the Global Forum. So, we want this interaction to be an opportunity for local artists to also seek to take their works to an international platform. And so far, in the last seven years, I don’t think we’ve done that. We can see our students, acting to uncover our residents, blossom within that area, and make it a safe place to work and to learn.

And as we continue to participate, we can formalise the sector more and more. It also increases the rewards that are available to artists, collectors, and society in general. Because as you know, art is something that depends on the perception and the exposure of society. So we do beauty and truth, and we try to find a way to show it to a better environment. And I think that’s what we should be working on.

Where is your favourite place of all the places you’ve exhibited your work around the world?

Well, right now, my favourite is the British Museum, where I’m showcasing works to do with the topic of human trafficking and political migration. It’s a place where you have six million visitors every year. I’m showcasing my work in the Special Project Room. It has broken all the records of attendance by the way. By the grace of God.

People used to spend 10 seconds, 20 seconds, and 26 seconds viewing them, and now people are spending minutes; they are repeating. It gladdens me because the topic itself is very important, and so we share this to create a lot of awareness about illegal migration, discrimination against migrants, and the unfair situation that has led to this scourge.

But more importantly, to share possible solutions to stop this human trafficking and illegal migration, we need to engage on the issue of the gate to reality, to see the background of human beings, to classify and apply it, and treat them better and also encourage the authorities to do what they are doing to stop it.

So, today, with IT, you can get more people employed, you can get people to be good translators, by taking over the internet, or by learning IT skills, like coding, and all of this, so that if we train the young people, or we train the most young people on the continent, they do not feel the need to travel, because anywhere they are, we can provide services over the internet, to people in India, China, anywhere, Canada, and get paid in foreign exchange. So, they don’t need to leave their homes, or they don’t need to want to travel or migrate anywhere, and wherever they get to, they become an asset instead of a liability. And so, we are pushing to be different; we are trying to be active. We have to now invent, on the continent, train a lot of young people, to create a fast culture of authentic internet, to obscure people, so that we can have people by bringing in the young people, and becoming assets to go over the continent, and, to look for the solutions, like, we also took on, to do a solution, and, so, I’m excited about that, and, to see what the future holds, as we continue to build upon that.

Oh, there’s a lot. As I said earlier, we have the Edo Global Arts Foundation.

Through my initiative for the Edo Global Arts Foundation, we’ve created a platform where we can support artists for residencies for workshops. We’ve created spaces for them where they can take off and practice until they are strong enough to move on, and various other activities which will help in the development of their careers. We also create opportunities for them to interact with international institutions and opportunities and get featured in all of these.

But more importantly, working with the governor and the governments of Edo state has resulted in the creation of MOWAA, the Museum of West African Arts, which will provide opportunities for over 30,000 citizens and planning for over 30,000 citizens. The Victor Uwaifo creative hub is there built as a sound stage and editing studio for creatives by the Edo State government.

These are projects that also create opportunities and training for the sectors, which we cannot even compromise, because in the building of the project, people are going to supply cement, people are going to supply sand, nails, and wood.

So the economic benefits are humongous. And then, it’s going to create jobs for curators, for those conservators, for students, for lecturers, for a lot of people. It’s going to become a repository research centre. It will also showcase artworks and give opportunities for artists to showcase their work, collect and visit. And then the tourism aspect. A lot of people are going to want to travel, to come visit and see the artworks, the bronzers, the institutions. So the economic benefits in terms of flights, transport, people paying for hotels, food, taxis, buying memorabilia; it’s a huge ecosystem that has resulted out of this. And not to talk of the public relations aspect, the effect it has on the confidence of our people, on the image of our country, of our state. And so, yes, it has been a very rewarding and exciting collaboration or service to the people and the government.

And yeah, I think that is what I will say for now.

Nigeria has a rich and diverse artistic heritage.

How do you see contemporary Nigerian art evolving, and what role does it play in shaping the nation’s cultural identity?

Well, I think it’s just amazing to see what’s happening in the contemporary art scene and to see how contemporary artists are contributing to the global artistic creative pool. I often say that art and creativity are our comparative advantage, and this uniqueness is something that, in sharing with the world, we retain an authenticity that cannot be replicated.

I think that hearing our voices, you know, just the culture is the way of living of the people. And so, to share our culture with the world and to share our creativity is also a way of marketing our people, marketing our culture. And to show that we are part of the global community, we can take our rightful place. When you look at what Afrobeats is doing to the world, a lot of people don’t realise that before Afrobeats, the visual arts was the critical ambassador for our country’s culture and image.

Our country’s image has contributed a lot to our economy. Because tourists come, they purchase stuff and all of that. And so, for me, I think the vibrancy of the creativity of our youths is being unleashed. And this is creating a lot of opportunity also for them and the economy. To harness this properly, it can become a huge foreign exchange earner, creating livelihoods for a lot of young people and a lot of other institutions that support the creative ecosystem.

Beyond your artistic endeavours, what other forms of art and creative expressions inspire you in your daily life?

Music is something that I cherish because I’m also a performer and singer. I compose music, and I find that this is great for inspiration. Music is great for expression, relieving stress, and saying the things you need to say as well as contributing thoughts and ideas and entertainment. Also, I think other things that inspire me are history, the beauty of nature, and human relationships because it’s also a beautiful thing to see people change, to see people grow, to see people blossom. It’s always amazing to experience. Yeah, I think I get my inspiration from human interaction, from nature, from music, creating music, listening to music, travelling, and seeing other cultures. It’s very important to learn about other cultures. Otherwise, you end up thinking that the grass is only green in your compound. But the more you learn about other cultures, the more you develop a healthy respect for the goal of humanity, and you begin to realise that the human story, the human experience, cannot be seen only from one perspective. It has to be seen from this collection of cultures and traditions and human experiences to understand it, to respect it, and to learn that in collaboration with other people, we can become like an orchestra which, when put together properly, can create the most marvelous music, the most marvelous and harmonious sounds. And it’s only with this healthy respect and this sense of respect that you realise that no race is inferior to the other, no race is superior to the other, and that when working together and having a healthy respect for each other, we can create a more beautiful and harmonious world.

You are also a singer-songwriter. How does your work as an artist influence your music and vice versa?

Well, basically like I said, the things that inspire me… are the things which also inspire my songwriting or my singing and performances.

Nature, the environment, what we are doing to the environment and also human interactions, what are we doing to ourselves and our environment, how do we create a more harmonious relationship between ourselves and our environment. All of these things are things that inspire me. Also, the joys of life, beauty in life, and discovering beauty affect my art. Because as you know, in composing music, you use different sounds, tones, instruments, and textures, so it is in art. In creating a painting, you use different colours, hues, different strokes, and different instruments to form the thoughts, to present it to the viewer or the listener in such a way that they can understand or grasp what you are trying to communicate. So, I see them all as similar in how they inspire each other. With music itself, I have experimented with a lot of genres. I have experimented with classical music using my language, the Edo language, to sing on top of classical compositions, and I have experimented with using the Edo language to sing on rock instrumentation, afrobeat, and all this to show that no language is inferior. If you say classical music is the highest form of music, then if my language can harmonise with it, it shows that it is not inferior or not underdeveloped. It’s something that continues to propagate the beauty of humanity.

A lawyer by training, Onah packs over a decade of experience in both editorial and managerial capacities.

Nwachukwu began her career at THISDAY Style before her appointment as Editor of HELLO! NIGERIA, the sole African franchise of the international magazine, HELLO!

Thereafter, she served as Group Editor-in-Chief at TrueTales Publications, publishers of Complete Fashion, HINTS, HELLO! NIGERIA and Beauty Box.

Onah has interviewed among others, Forbes’ richest black woman in the world, Folorunso Alakija, seven-time grand slam tennis champion, Roger Federer, singer Miley Cyrus, Ex Governor of Akwa Ibom State, Godswill Akpabio while coordinating interviews with Nigerian football legend, Jayjay Okocha, and many more.

In the past, she organised a few publicity projects for the Italian Consulate, Lagos, Nigeria under one time Consul General, Stefano De Leo. Some other brands under her portfolio during her time as a Publicity Consultant include international brands in Nigeria such as Grey Goose, Martini, Escudo Rojo, Chivas, Martell Absolut Elix, and Absolut Vodka.

Onah currently works as the Editor of TheWill DOWNTOWN.