Talking Arts, Culture And Heritage With Nike & Reuben Okundaye

After a country’s name, its cultural identity is its most significant descriptive marker. Our culture, in its entirety, can be traced back to the time before westernisation conditioned the entire global population to dance to the colonial tune of yesteryears, ascribing a definition to civilisation that looks nothing like what our forefathers knew. Culture is the way of life that announces our ‘Nigerian-ness’ even before our oppressors christened us. However, for generations, we have steadily drifted from our culture as we know it.

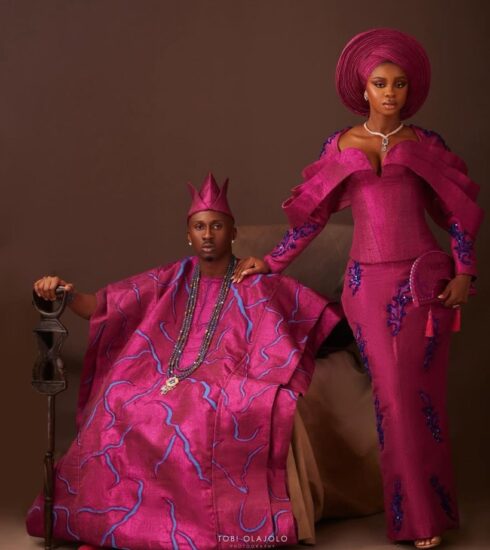

This issue, an ongoing dilemma, was the topic of discussion when DOWNTOWN’s Editor, Onah Nwachukwu, sat with two of the most influential custodians of the Nigerian culture alive today in the Owner and Curator of the Nike Art Galleries in Osogbo, Lagos, Ogidi-Ijumu (Kogi State) and Abuja, Chief Mrs Nike Monica Okundaye, popularly referred to as “Mama Nike,” thanks to her lifelong philanthropy empowering women across the world, and her husband, Ex-Police commissioner, Reuben Osaruyi Okundaye. The couple talked about art as our biggest cultural heritage, its preservation and representation in fashion, and the manipulation of our ancestral religions by our colonial masters who were on a mission to whitewash our land and strip it of its resources and cultural blessings.

As a renowned exhibitor of African cultural art, what is culture to you?

Nike: Culture is our heritage. It is part of life. Growing up, you will follow your parents and their culture, the way they eat, dance, talk, and even proverbs, everything is part of our culture, and we must always adore it. After a country’s name, the next important thing is its culture. We should love and cherish our culture.

Reuben: It is what our forefathers have done in the past to move the country forward. How people acted and behaved in the past, and have been passed over from generation to generation, is our culture. This includes all activities of life, the way you sing, dance, play, do marriages, and celebrate birth and death; they all centre on our culture.

Then if you go further to ask about our heritage, it is carried beyond what we are repeating, even to date, and trying to amplify what our forefathers had done in the past. Heritage and culture are interwoven.

How do you think we can preserve our culture because it looks like we are losing it?

Nike: To preserve our culture, we must continue training people who can take over after us. That is training the generation. Sometimes it may not even be your child, biological or adopted, but if you see someone you can train, then train them. It’s training the trainers because if you train somebody, they can train another person.

The only way is to keep passing the knowledge of our culture to our children so we will not lose everything in the future because, as it is now, we are losing everything. In those days, they would tell you not to sit on the mortar because they didn’t want you to fart inside it. When you’re eating, they would say, “Don’t stay by the door,” because if someone is passing by, they don’t drop sand in your food. If you are eating, don’t talk.

That is because the food could go to your head or nose, and the person can die from it. There are many things that people are doing now that aren’t in our culture. When they go out to eat nowadays, they go there to talk. We don’t talk because we eat pepper; foreigners talk over meals because they don’t eat pepper. The food is different, cold food is different from hot food, and that is also culture, the way we eat.

Let’s talk about culture and fashion. What do you think our designers can do to preserve culture through their design while selling it?

Nike: They can preserve and sell our culture through their design by using symbols—those old symbols that people communicate with. Like when Fela said water has no enemy, there is a design from the textile that is called water. So that design is telling you, ‘I’m like water; I’m not your enemy.’ Then we have a design that is called ‘the presence of God in my life.’ There are a lot of symbols that fashion designers can use and also, and they can go back to the natural colours which are dying off. Look at our hair; now, people are sitting under the dryer. The first time I wanted an afro, I went under the dryer and fainted. I was there for three hours; my brain was cooking. In those days, you will braid your hair naturally, wash and comb it, and receive joy. The comb as a symbol means the road is open, the joy is accepted. Even geckos that people chase to kill help with ridding your house of little flies and spiders which could be poisonous. These are also part of our symbols. There is a design in Lagos called the goddess of the Sea. It consists of twenty-eight symbols; the umbrella, my head is correct, etc. These symbols can be placed on garments and put on the runway.

There are so many things that we are destroying ourselves (that could have been used for fashion designs). Look at cotton, 100 percent cotton.

Northern Nigeria used to export cotton before, but now we import it. The same thing happened with palm oil.

Our molue (long commercial buses) are now going extinct. We have to print them on the adire for our children to see. Our coins, which we no longer spend, we put in the gallery so people can see them. All those are gone, but we can still continue with the model because technology has changed everything. We are happy that we have social media now. In our own time, when we were going to school, we were only using pencils, not even biro. But now, children are using computers. That is why we need the youths; we need them more. But we still have to pass on this knowledge to them and say this is your culture.

You can use it as a designer. Look at this head tie I’m wearing; it’s called auto-gele. I went to do it in Tejuosho to show the women. When you train a group of women, you train the nation. So now, people are not paying five thousand Naira to do the same gele anymore.

Then we have the autogele, which you can just wear on the go. Before now, you had to spend three hours wearing the gele and having headaches because of it. And gele is supposed to be like a hat that brings you joy. Professor Wole Soyinka once wrote a book he titled Gele Gala, and made me the first lady of gele. It makes me happy whenever I see it.

You talked about the goddess of the sea as a god. Some people will argue that we should distance ourselves from such gods. Some argue that they are not bad but a part of our culture. Do you think that it was the white people who came and made us see them as bad? What do you think?

Nike: When the white people came, they said we should throw our religion away so we could embrace Christianity. But this new pope is telling people to embrace their culture. So there is a story with Pope Francis. They saw my work at the Vatican and asked me to return to our source and tell the story of how the Osun goddess gave people babies and whatever they wanted. It’s just like going to church and making a testimony.

In the same way, people make pledges and say, “Osun, if you can do this for me, I will come back and do that for you.” They are not using human beings for worshipping. But our people, because they only go one way, immediately hear idol, and everything you do is an idol, even creativity. If you carve wood, they will say it is an idol. So they have to come back to their senses and see that we used our hands to create all this work. Cowries are frowned upon today as people identify it as an idol element, forgetting that we used to spend it as money back in the day. Or how they look at you differently when you go to Osun when it is the same as going to the beach.

Reuben: A community that has no culture or heritage is not a community. That community does not exist. It is highly regrettable that we have given away our own religion to our conquerors who came here, conquered us, ruled over us and enslaved us. They killed our own way of worship. We had always worshipped our gods before the white men came in. For those gods to be called satanic and fetish is one of the highest forms of wickedness that has been perpetrated on our people. Christianity and Islam are quite alien to us. But our foreign masters came in and told us that we should not serve our god but theirs. Neither Jesus Christ nor Muhammad was Nigerian nor African, but most unfortunately, our foreign masters came and ordered us to dump our own means of worship and started calling it all kinds of bad names. If you want to kill a dog, give the dog a bad name. That is what they did to us, and it is still one of the major problems that we have in this country.

They taught us to hate and see ourselves as different tribes and religions. If you decide to still believe in what our foreign masters asked us to do and not chart a course of our own, it is most unfortunate. I remember when India was granted independence, years before us, Gandhi told all Indians to dump the English language and religion. He told them not to write in English, and they developed their own character, stuck to Hindi, and practised their religion, which they still practice today. India is very well advanced; I think they have the biggest democracy in the world today with a population of one point something billion. In everything in life, they are doing very well. People would leave here for India to seek medical help. It is most unfortunate. When I’m looking back and relating all this, it reminds me of what our forefathers went through. The bitterness in their heart comes back to me, which is most unfortunate.

Regarding training women, do you have a foundation or an organization?

Nike: It is something I do by myself. So I started the training in 196; I was born into poverty. I lost my mother when I was seven before I got to primary six, and I saw how women suffer. Because of five Kobo, they could be beating themselves, and one man would marry maybe 20 of us and use our intelligence to say, “Oh, they have nowhere to go; let’s put them as workers in the house.” So when I came back, I was given the opportunity to travel to the US. But before then, I started the centre because my former husband had 15 wives and every time, we fight because of 1 or 2 Kobo, for what? So I decided to train them. If this handwoven skill can take me to America, it can also carry you. That was how I started the training and decided to share my knowledge with my colleagues. So I went to the garage to reach out to the girls hawking there because, in those days, that was where girls were raped, had early pregnancies and were rejected.

I started the Training The Trainer initiative, and they were using police to arrest me because I was going into the work of men. But now, I thank God there are women directors and filmmakers in our lifetime. I started the training centre with 20 girls in Osogbo, my headquarters. From 20, they became 40, but when I train you after six months, I will say you have to train other people. As I trained you free of charge, fed you and gave you accommodation, you must do the same to others. The artists only give me 10 percent if I sell their work for them. And some of my artists that are close to me, like my children, sometimes gift me a painting once a year. Then I will sell it and use it to run the workshop. After opening the Osogbo branch, I set up another branch in my village.

I trained about 265 women in three months. The women, mostly married, can do textiles in their own villages. Then in 1996, I opened a centre in Abuja. It is for people who go to Abuja and can’t get a job. I moved to Lagos in 1992 when the road wasn’t safe anymore, and people couldn’t risk coming to Osogbo because of insecurity. I now opened a centre in the house in Lekki here. They said they didn’t want any business in Lekki, and I told them it wasn’t a business; it was to train those women living in the Shanty.

What made you interested in arts?

Nike: Because of poverty. I didn’t have money to go to school, but I managed to train myself through Primary 6, and my father, called Asindemade, was also an artist—those people who stitch beads on the crown. My mother was too. If I hadn’t become an artist, the other opportunity for me was to become a nun because I always liked how the Reverend Sisters helped other people, providing them with jobs and skills.

Do you think we have a means of preserving the returned artefacts?

Nike: Right now, we have no means of preserving them unless they send some people for training.

Those people who will be trained will be the ones to guide everyone else on maintenance because sometimes there is no electricity for one or two days, and these things have to be kept at a specific temperature.

In those days, there was no pollution in the air. Nowadays, generator smoke will darken your work. To return them is not the problem; to maintain them is. If they can put the right people to train them on maintenance, I won’t go against it. But for them to bring it and dump it for the same people?

Not all the artefacts were stolen by white people; some were sold to them by our people. They then lied that white people stole it. Some of them are the victims because they are returning what they bought.

Reuben: Why not? We created them, and before the Europeans stole them away, they had been with us for thousands of years. So obviously, we created it, and we know how we had been keeping it, so it will be an over carriage for anyone to suggest that we don’t know how to take care of our belongings. I cannot imagine when someone will just come and say they want to take your house from you and take care of it for you. That is obnoxious, to say the least. We have the brilliant knowhow to keep our things. That is what God has given to us on this land.

How did you start making your headgear look so elaborate?

Nike: In those days, the head-tie symbolised a successful housewife that looked after her husband. Our head-tie and hair are our crowns. As the queen in the UK wears a crown, we also wear our hat as a crown.

When Mandela died, our oga, Professor Wole Soyinka, said we should do something depicting a giant like Mandela. So I decided to enlarge my head tie because Nigeria is a quarter of Africa’s population. Since we are the giant of Africa, let’s make head-tie giants. It represents my country, Nigeria, to show how we bring ourselves together as a family. No matter what happens, we are our brothers and sisters’ keepers. So, I said, ‘Let’s put all the headties together and make it elaborate.’ Let people love it, and give them something to talk about because sometimes, if they don’t talk about you, the person is dead.’

Why are art and culture important to you?

Nike: Art and culture are important because it is a way of life. Art is like therapy. People don’t know what it can do. Art can save lives and take you to a greater point in the future because you can say this is our oil. Art is life; life is art because when I am working, I work with my soul. I put my spirit into my work.

A lawyer by training, Onah packs over a decade of experience in both editorial and managerial capacities.

Nwachukwu began her career at THISDAY Style before her appointment as Editor of HELLO! NIGERIA, the sole African franchise of the international magazine, HELLO!

Thereafter, she served as Group Editor-in-Chief at TrueTales Publications, publishers of Complete Fashion, HINTS, HELLO! NIGERIA and Beauty Box.

Onah has interviewed among others, Forbes’ richest black woman in the world, Folorunso Alakija, seven-time grand slam tennis champion, Roger Federer, singer Miley Cyrus, Ex Governor of Akwa Ibom State, Godswill Akpabio while coordinating interviews with Nigerian football legend, Jayjay Okocha, and many more.

In the past, she organised a few publicity projects for the Italian Consulate, Lagos, Nigeria under one time Consul General, Stefano De Leo. Some other brands under her portfolio during her time as a Publicity Consultant include international brands in Nigeria such as Grey Goose, Martini, Escudo Rojo, Chivas, Martell Absolut Elix, and Absolut Vodka.

Onah currently works as the Editor of TheWill DOWNTOWN.