Inequality In The Kitchen: A Look Into The Male-dominated Culinary Industry

Freepik

As we enter a time when more people are questioning things, and the gospel of feminism is beginning to spread to those who care enough to be at least involved in the conversation of gender equality, one question has been recurring through it all: ‘Who should cook in a family?’ Depending on who you ask, the answer is pretty straightforward.

In the patriarchal world that we live in, gender norms were formed to dictate to people what to do. One of the most prevalent family dynamics is that women are caretakers of their households, so everything that concerns the upkeep of it, especially feeding, is her task. So far, this phenomenon has kept the average woman boxed in as a potentially perpetual house cook. Did I say ‘the average woman?’ Remember in 2016 when our commander in chief, President Muhammadu Buhari, basically relegated his wife, Nigeria’s First Lady, to the kitchen? Definitely not the average woman.

During a press conference with then-German chancellor Angela Merkel, President Muhammadu Buhari was clearly miffed at being asked about criticism of his government’s performance by his wife, Aisha Buhari. He responded by reminding Nigeria’s first lady where her place was: in his kitchen, living room and “the other room”. This sparked a global conversation as most people online think he was wrong for making blanket statements like that. But this is how the majority of the country thinks.

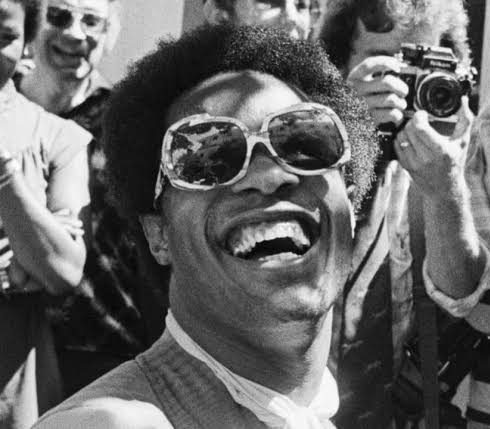

Chef Imoteda Aladekomo

One of the many biases women face is the expectation of being completely domesticated. The notion that women belong in the kitchen has existed since the beginning. When discussing what each marriage party brings to the table, the duties allocated to women are often similar to the KPIs designed for a househelp. One would think the food industry is at least a market that women dominate.

According to a list published by wealthygorilla.com, only three women are ranked among the world’s top 20 best-paid celebrity chefs, enunciating the ridiculously huge wealth gap within the culinary industry.

In the United States, according to the Labor Department, while more than half of culinary graduates are women, fewer than 20 per cent of working chefs are women. The figures are even more staggering when talking about leadership. Women comprise just 7 percent of head chefs and restaurateurs across the country today.

For female chefs in the UK, the specific pressures they have been under for so long — logistical and financial difficulties surrounding maternity leave and childcare and a perceived connection between one’s ability to do the job and physical strength — have been compounded to a new degree by the widespread workplace impact of the pandemic. While it is clear that the problem is systemic, the unforeseen challenges of the last 16 months have brought with them disproportionate burdens on women, which are, for many, entirely and depressingly predictable. “I think it’s almost expected of women that, if you’re going to be in this man’s world, we need to see you be a bully,” says London-based pastry chef Taylor Sessegnon Shakespeare.

In Nigeria, where women have been ordered to find a home in the kitchen, although women heavily populate the food industry on the small-scale spectrum, the country’s most prominent chefs and restaurant owners are men.

Cooking is one of the most essential skills for survival. Regardless of gender, feeding is non-negotiable, and so is sourcing for food. As Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie wrote in Dear Ijeawele, or a Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions, “The knowledge of cooking does not come pre-installed in a v-gina.”

Self-identifies as a middle child between millennials and the gen Z, began writing as a 14 year-old. Born and raised in Lagos where he would go on to obtain a degree in the University of Lagos, he mainly draws inspiration from societal issues and the ills within. His "live and let live" mantra shapes his thought process as he writes about lifestyle from a place of empathy and emotional intelligence. When he is not writing, he is very invested in football and sociopolitical commentary on social media.