Behind Closed Doors: Unravelling The Scourge Of Domestic Violence In Nigeria

Beneath the surface of Nigeria’s cultural heritage, vibrant spirit, colourful tapestry and wedding celebrations, a grim reality persists—domestic violence. Behind closed doors, countless individuals endure unimaginable pain and suffering, trapped in a cycle of abuse that knows no boundaries. We shed light on the disturbing statistics and the stories of resilience as Nigeria grapples with the issue of domestic violence.

A Troubling Reality: The Statistics

According to the National Demographic Health Survey (NDHS) conducted in 2018, domestic violence remains alarmingly prevalent in Nigeria. The survey revealed that:

1. One in Three Women – Yes, you read that correctly. One in every three women in Nigeria has experienced some form of domestic violence, be it physical, emotional, or sexual.

2. Urban vs. Rural Disparities – While domestic violence is pervasive in both urban and rural areas, the NDHS highlights that women in rural areas tend to experience higher rates of domestic violence.

3. Age and Education Factors – Shockingly, young women between the ages of 15 and 24 years are more likely to experience physical violence, and the level of education seems to have little impact on the occurrence of domestic violence.

4. Underreported Cases – Despite these alarming figures, domestic violence cases remain vastly underreported due to the stigma, fear, and lack of awareness surrounding the issue.

Understanding the Cultural Context

To combat domestic violence effectively, it is essential to delve into the cultural context perpetuating this harmful behaviour.

Nigeria’s cultural norms often emphasize male dominance and a patriarchal family structure, creating an environment where women may be seen as subservient and subjected to abuse. Challenging these deeply ingrained beliefs and norms becomes crucial to bring about lasting change.

The Impact on Victims and Society

Domestic violence inflicts profound wounds on its victims, leaving scars that extend far beyond physical injuries. The psychological trauma endured by survivors can result in long-term emotional damage, affecting their self-esteem, mental health, and overall wellbeing.

Moreover, domestic violence also affects children who witness such abuse, perpetuating a cycle of violence through generations.

The societal impact is equally devastating,

1. Awareness and Education – To combat domestic violence, widespread awareness campaigns are essential to challenge prevailing cultural norms and empower individuals to recognise and report abuse.

2. Legal Reforms – Strengthening existing legal frameworks and enforcing laws that protect victims are critical steps in combating domestic violence. It is vital to ensure that perpetrators face the consequences of their actions.

3. Support Services – Establishing comprehensive support services, including shelters, counselling, and hotlines, can provide much-needed assistance to survivors seeking a way out of abusive situations.

4. Community Involvement – Engaging community leaders, religious institutions, and local organisations can foster a collective commitment to ending domestic violence.

Domestic violence. Mother and daughter suffering from home abusement, mom protecting kid from father’s fist.

Domestic Violence: A Family That Cannot Thrive

Domestic violence can be physical or psychological and can affect anyone of any age, gender, ethnicity, or sexual orientation. It may include behaviours meant to scare, physically harm, or control a partner. And while every relationship is different, domestic violence typically involves an unequal power dynamic in which one partner tries to assert control over the other in various ways.

Nigeria has a deep cultural belief that it is socially acceptable to hit a woman to discipline a spouse.

Cases of Domestic violence are on a high and show no signs of reduction in this part of the world, regardless of age, tribe, religion or even social status. According to the CLEEN Foundation reports, one in every three respondents admitted to being a victim of domestic violence. Often backed as a culturally accepted correctional method, Nigerians are not new to the concept of physical violence. The sense of ownership that sees a parent physically abuse their child without repercussions transcends to men hitting their wives only to be met with the question, “What did she do?” When the news of the passing of famous gospel musician, Osinachi Nwachukwu broke on the 8th of April 2022—the one that made it to mainstream media—Nigerians reopened the conversation on domestic violence. For friends and family, recounting her sad experiences in marriage has been a nightmare. Accounts of how her husband, who doubled as her manager, allegedly hit her consistently, spit on her head and face to show his feelings of disgust towards her, hindered her from recording specific songs and working with certain artists, and even locked her up in the house, was brought to light.

Osinachi’s ordeal sparked a nationwide debate with one question reverberating at the end of each digital town hall session that was held online: Why didn’t she leave?

The Divorce Stigma: A Deadly Price

Divorce in Nigeria is not a common practice. If you ask most people about it, they will tell you that divorce is not our culture. So what happens when a marriage is no longer working?

To address the stigma around domestic violence and the eventual solution–divorce, we must discuss society’s fixation on marriage. An abusive marriage often constitutes a perpetrator—who is usually a repeat offender using insults, threats, emotional abuse, and sexual coercion as their tool—and a victim bereft of self-esteem. Some perpetrators may use children or other family members as emotional leverage to get their victims to do what they want.

Victims of domestic violence experience diminished self-worth, anxiety, depression, and a general sense of helplessness that can take time and often professional help to overcome.

The easier way out would be to point fingers at a divorce law system that is almost not helpful or enough help facilities for a teeming population of victims of domestic violence. However, one cannot help those who don’t want to be helped. The stigma around legal divorce or just regular separation is at the core of why women would rather remain in an unloving marriage. The sense of helplessness—and uncertainty of where to go after leaving—that most women are presented with is the singular reason why not many women take the plunge. Since marriage has been marketed to women as a sign of fulfilment, and women who don’t end up getting married are often considered a failure, it is not rocket science to see why they would opt to remain in one regardless. After all, nobody wants to be seen as a failure. The same society that tells a woman to run for her dear life is the same one that asks her why she is unmarried at a certain age. The odds are stacked against victims of domestic violence, but we are not too far gone as a people; we can still retrace our steps back to the very beginning to ask questions about the essence of marriage so it becomes clear that although the institution of marriage is a very beautiful one, it is not a do or die affair.

The Ripple Effect: Parenting

There’s collateral damage that comes with an unhappy home, it’s not the couple that suffers. The Nigerian family unit has for so long been one held in high regard by, well, Nigerians. The phrase “this generation” has probably seen its highest usage in the internet’s history. When used in parenting contexts, it is often to address the inappropriate behaviours of children—which is not peculiar to this generation—that end up in the public domain for life.

It seems like it’s now an annual occurrence—an unfortunate trending topic with children at the centre of it. “How have we gotten here?” Is the question on the majority’s lips as they engage, very much fiercely, in the best way to raise children.

Children are vessels waiting to be filled, and that is any parent’s only job—to fill that vessel.

No, bad behaviours and immoral acts are not new to this generation. However, they—the kids—are the ones bearing the brunt of having a permanent digital footprint with every ignorance they are caught in. A bad child is a product of bad parenting, and if you don’t know anything about raising a child in today’s digital age, you must know how incredibly difficult it is.

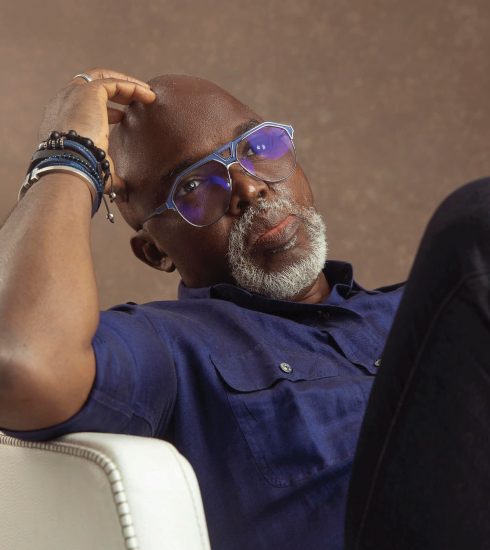

Late Osinachi Nwachukwu

Marriage Culture In Nigeria, a Breeder

In Nigeria, very few things (if anything at all) trump society’s perceived importance of marriage.

Especially for women who are believed to be racing against a biological clock, the gospel of marriage has been preached far and wide in over 525 native languages spoken in the country. And because of that, it doesn’t matter what your personal definition of fulfilment is; if you are not married, you are doing life the wrong way. This ideology is very harmful.

Historically, women are raised to aspire to marriage. In a traditional setting, practically everything that a girl is taught from infancy till early adulthood—or in the case of victims of child marriages up north, their preteen years—is how to make and keep a home through tolerance, service and compromise, with the predicted fulfilment that marriage comes within view. As this takes the place of actual women empowerment, most women are not armed with the necessary skill sets to navigate life independently. So marriage is not only socially beneficial, it also has a ridiculously impressive economic value. For most women, this is a no-brainer.

For men, the conversation around marriage is a tad different. Throughout history, men have been raised to see themselves as providers and shot callers. Unlike girls, boys grow up in an environment that doesn’t prepare them for what dealing with a woman is like. When a girl does something questionable, the question is often along the lines of “Is that what you will do in your husband’s house?” Whereas when a boy acts inappropriately, questions of how he intends to treat his future wife are rarely raised. In a society heavy on financial well-being, no economic value is attached to marriages for men. And due to their inflated sense of ego as the perceived providers and the leaders of the pack according to religion and culture, many men run their household as a dictatorship instead of a partnership.

Make no mistake; marriage is beautiful. The older we live, the clearer the need for companionship becomes. “Do you want to die alone?” Is often asked to invoke fear in people who have chosen to remain single. There is no denying that having your own personal person with whom you share similar goals and aspirations can be a useful life hack—navigating life alone could prove to be challenging. An example of some of the perks that come with a loving and lasting relationship is in Joke Silva’s commitment to her 34-year-old marriage to Olu Jacob through his ill-fated dementia ailment. When two people wed, they typically exchange vows that say something to the effect of promising to be together for better and for worse, for richer or for poorer, in good times and bad, and so on, culminating in the phrase “till death do us part.” These words sound so blissful and reassuring that people yearn for that level of love and commitment. But it can also easily go south.

The complexities of each human life make cohabitation somewhat difficult.

And because of the power dynamic in a typical heterosexual relationship, faulty communication, and lack of mutual understanding, some marital unions fail the test of time. In Nigeria especially, cases of actual violence in marriages are prevalent, with many undocumented because of the stigma around it.

“For better or worse.” When used in a context other than marriage, these words often imply deep commitment, intentional service and the promise of a lifetime warranty that can only be annulled by the demise of one or both parties involved. “Till death do us part” affirms that inevitable annulment because every living being must die at some point. Of course, we don’t hear of cases outside marriage when these phrases are used, neither in business partnerships, family relationships or friendships. But how did marriage get this immense level of PR that, although different from culture to culture, dictates that each variation of it comes with the swearing of oath—legally or not—to permanence?

Conclusion

As Nigeria marches towards progress and development, it must confront the dark reality of domestic violence head-on. By acknowledging the statistics and stories behind closed doors, we can collectively create a society that cherishes respect, empathy, and compassion. It is time for Nigeria to unite against domestic violence and break the silence, offering hope and healing to those trapped in the shadows. Together, let us empower survivors and build a future free from the shackles of domestic violence in Nigeria.

Self-identifies as a middle child between millennials and the gen Z, began writing as a 14 year-old. Born and raised in Lagos where he would go on to obtain a degree in the University of Lagos, he mainly draws inspiration from societal issues and the ills within. His "live and let live" mantra shapes his thought process as he writes about lifestyle from a place of empathy and emotional intelligence. When he is not writing, he is very invested in football and sociopolitical commentary on social media.