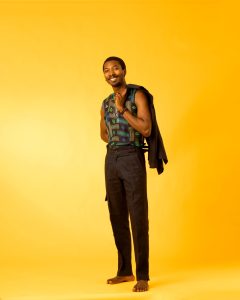

Say Hello to Grammy Award Nominee, Made Kuti

You cannot tell the Nigerian story without mentioning a particular name—Anikulapo-Kuti. Holding the reputation as one of the strongest households in the country, the Kutis have been known for their immense contribution to nation-building in the form of activism and pioneering a whole music genre that has put Nigeria on the map for three different generations to date.

Last year, a new Kuti generation was introduced into the music industry. After the release of his debut album, For(e)ward, on which he flexed his musical dexterity as he played every single instrument, Omorinmade Kuti known professionally as Mádé Kuti couldn’t have asked for a bigger entrance. His joint album titled Legacy+, which he made together with his dad, an afrobeat icon, Femi Kuti, bagged a Grammy nomination, making him the first-ever Nigerian with a Recording Academy recognition for their debut musical project.

Mádé, who shares the same alma mater as his grandfather and afrobeat pioneer, Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, sat down with DOWNTOWN’s Kehindé Fagbule. In their conversations, they discussed his musical journey that subconsciously started when he joined his dad’s band at age six, and what it meant growing up in the New Afrika Shrine. He also makes mention of what the future holds concerning his career trajectory and owning his craft, not as Fela’s grandson or Femi’s son, but as the multi-talented Grammy award nominee, Mádé Kuti.

Many people recognise the New Afrika Shrine as a recreational place to blow off steam and whatnot, but you grew up there. What was growing up like?

It was enlightening because my dad made the shrine with a very clear purpose. It was supposed to be a space for liberal thoughts, so anybody that came in would feel like they have the freedom to express themselves and to think. All I understood as a child was that a lot of people misunderstood what the place represented. I never really understood why because I did not have a greater understanding of journalism and media, and the kind of misconceptions that they have about the family. All I knew was that I watched my dad play four times a week every week, and three of those shows were free. The shrine was always full at the time—for each show, there was nothing less than 3,000 people in the shrine and across the street. Also, the area that we were in wasn’t as eventful then as it is now, so everyone that came there was coming to the shrine.

As a child, all I understood was that it was a lot of music and politics. People come from all over Nigeria, there are a lot of white people, and a lot of pictures of people that I didn’t recognize at the time. People like Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Marcus Garvey, and so on. Because I didn’t recognize them, somewhere along the line, I started questioning the images that I was seeing, which is really what the shrine is. If you come there in search of enlightenment, you will find it; it is that kind of space. And because I researched to figure out who those people are, that then puts my person and identity on the kind of path that I now eventually choose to be on. If I didn’t know those people, what they did and represented, I probably wouldn’t be who I am today.

I would have guessed that was from your granddad.

Yeah, but you see, something about family is if I allow myself to be boxed up in the legacy and not see the efforts of like-minded people as us, I wouldn’t understand what the legacy represents and who influenced who we are as Kutis. If I didn’t look back to respect a man like Marcus Garvey, to make one of those first bold moves towards the Pan-African experience and not understand what black star represents, for instance, I’ll be part of a legacy but I wouldn’t understand what it represents.

We are people who are conscious of our past and we know that we need that information to be able to build any kind of hopeful future that we are fighting for.

You started playing the trumpet at the age of 3…

I made sounds [laughs]. I probably started playing and taking it seriously when I was 6 years old.

But then you were still going to school. How were you able to joggle that?

Just private lessons. I was somewhat close to my dad’s band and I always used to tour with him. So anytime I showed interest in any particular instrument, he’d ask one of his band members to teach me. So that is how I picked up the trumpet. He taught me the sax himself, but the drummer at the time taught me how to play the drums. I was also taught the guitar and keyboard. But as soon as I finished [secondary school] and went to London, I did classical piano very seriously for two years and that was the only instrument that I played. I was practising six hours every day while going to school. Just as I was almost done with school and was about to return home, I realised that other than the piano, I hadn’t touched all the other instruments that I used to play as a child, in a really long time, so I decided to relearn everything. In the case of the trumpet, I had to start from beginner-level books. I also learnt from YouTube, I taught myself all the instruments again. Because I had just come back to Lagos and I was practicing so much and also composing. It was then I decided that if I’m writing all this music and playing all these instruments, maybe I can write an entire album for myself.

You talked about not wanting to be put in a box as a Kuti, so at what point did you realise that you were going to do music? Because you could have been anything else.

Music was probably the easiest decision for me because I was touched by it in the purest way and that is experience. By watching my dad play at the shrine, I got to see the interaction between him and the crowd. I also saw the compositional process when he wrote the songs and the rehearsal process when he gave out the parts very impatiently to all the musicians. In addition to this, I saw the performance and still followed him to the studio to record, and also on tours. So the experience was with the entire process of music. With all of that, it was never a question if music was the thing. It was always a question of ‘if I do music, what will I do on the side?’

You went to the same school your granddad finished from…

That was a bit unintentional. So Trinity is one of six conservatoires in the UK and I applied to all of them, except one. But at the time, my musical theoretical knowledge wasn’t great—I could read and write, but I didn’t know the history of classical music. I couldn’t identify the eras of classical music.

Based on the compositions that I did to get auditions to those conservatoires, all of them gave me auditions. Royal Scotland was willing to offer me admission but on the condition that I took an English test which I then declined. The other place I auditioned, Birmingham conservatoire, asked me about Western music and I just couldn’t answer them, so they turned me down immediately [laughs].

The Royal Academy wanted me to identify pieces and the eras of music by listening to them and I just wasn’t informed about those kinds of things, I didn’t have the knowledge of it at the time, so they turned me down as well.

It was a period of madness for me, it was like four months of chaos. I was so upset by the other two rejections that I missed the date for the Royal College. That was like a moment of next-to-depression because the Royal College was where I wanted to go.

The last place on the list of auditions was Trinity. What happened with Trinity was that I had had enough experience on how to get in from my previous rejections. So I studied all the questions that I couldn’t answer in previous auditions, I was very prepared. I answered their questions and gave them the impression that I had been studying for a long time whereas I just heard about them like two weeks before the audition [laughs]. Because I came in that way, and sort of understood the sort of questions they would ask beforehand, I laid out my intentions for Trinity clearly which was ‘putting afrobeat in the contemporary classical setting using the instrumentation of the orchestra to really push out the ideas of core afrobeat musicality.’ That was how I advertised myself to them. They gave us a written exam which I didn’t do well in, but my audition was good enough for me to get a place. And that year they accepted the largest number of people they had ever accepted, which was 15 people. So by the time we finished, only seven to eight people graduated, most people gave up halfway, it wasn’t easy.

Being at Trinity was not hundred per cent intentional as I didn’t go there because Fela went there. But having then gone to Trinity, I realised that of all the other places, Trinity was the place that I had to be because it was open-minded. The jazz department was so free, the people were so natural. Trinity has now pushed out all these musicians that are now making waves in London. The four years of education I got there were entirely paramount to me being the kind of musician that I want to be.

You have been making music for a long time…

Yes, I think I’ve been writing music—if you consider the creation of music as just making something from where there’s nothing— longer than I’ve been playing music.

Why did it take until 2020 to release your first single?

I was never rushing at first and I really wanted to finish my education at Trinity. But when I got those rejections at those conservatoires, before I did my audition at Trinity, I started writing an album in the event that I didn’t get accepted in the university. So before Legacy+, I had already written an album with about 10 tracks and now it is somewhere in the archives. And when I finished with Trinity I had the space and time to write again.

So you released the debut immediately after graduation?

As soon as I left Trinity, before graduation, I had already joined my dad’s band because he had a couple of tours and his bassist absconded on tour. I had a British passport so he didn’t need to get a visa for me, and I was the easiest candidate to be a part of ‘Positive Force,’ which is his band. I played bass with my dad for a year and a half while recording the album. I had had my last class in school, so in between, I just went back for graduation.

You played every instrument on the album. A lot of people delegate that. Why did you decide to take the arduous route?

I think the main reason why I did it was because I understood that it was the first time I was coming out. And I didn’t want to come out in an average way after waiting for so long. So yeah, if I can play the trumpet, sax, drums, bass, guitar, keys, do the vocals, the background vocals, write all my music, do the mix and arrange it by myself, then it would mean nobody, as far as I know, has done it in that way. That was my intention; you know the Kutis, we are always setting standards on high thresholds, so I was like ‘what’s mine going to be?’ I was 21 or 22 and said, “let me play all the instruments on this album.” I had the time to sit down, work through this thing and execute it. If I can do it, I can do it. I spent three months practising; 10am to 11pm that’s 13 hours every day. I had already written the music and then I was just practising it. We got to the studio and had 16 days to record the entire album. We did it in my uncle’s studio in Paris. It was just me and one other guy.

And it became a beautiful work of art nominated by the Recording Academy for a Grammy award.

Exactly! My dad had already recorded his album by the time I started mine. He had already decided that it would be a joint album and he didn’t hear my side of the album [laughs].

I was expecting that both of you would be on the same tracks…

Kutis are very independent composers. We’re not the type to share ideas or to be influenced in our compositional process. My dad wrote all his music, uncle Seun wrote all his music, Fela wrote all his music as well. So when we were writing this album, I had heard my dad’s songs because he performed them at the Shrine and I played bass and sax. But my dad didn’t hear my music until after the album release [laughs]. His fear was that he invested all this money into this project; but yes, it worked out well. I think one of the things that has always propelled me to work harder and really push myself with those kinds of tasks is the amount of faith that my dad has in me. It influences my intention. It always makes me more purposeful. He trusts me to do this, so I’m going to do it well. My dad is 60 years old this year, everyone in the band is probably 40 or older and they work. They play two times every week, and they tour five shows weekly. I have told every member of my band that our work ethic cannot be less than this. So I make sure that when we practise, we practise till we want to drop. That’s also my way of telling the band my intentions. This is where I plan on going, this is the work ethic that I want the band to have; if you are in line with it, you will have a great time but if you’re not, this band will be a nightmare for you. So everybody has to really decide what they want. My dad influences my decisions more indirectly than anything else just by things that he values.

Walk us through the moment you found out that your debut album was nominated for the Grammys.

I went mad. We were on tour, on break in a tour bus in Belgium, we had two off-days. And I had been checking because I knew that the nominations were being announced that day so I was watching live. I was expecting that my dad would get a nod, but he put out a solo project, Stop The Hate, at the same time we released Legacy+, so I wasn’t sure which of the albums they would nominate. The nominations for Best Global Music Performance was announced first and it featured Pà Pá Pà, a song by my dad and I went mad. I was just happy that he was nominated because it is like they don’t want to recognize the effort and amount of musicianship that he puts in. Then the Global Music Album category came around and I had already thought that because they nominated my dad in the previous category, they wouldn’t nominate him in this one. I actually ran around the bus when Legacy+ was announced. Because the album didn’t get commercial success, it was nice to see that musicians respect it.

You are going up against afrobeats giant, Wizkid at the Grammys; someone your dad shares a hit song with in Jaiye Jaiye. Should we be expecting a crossover from afrobeat to afrobeats with you sometime?

I’ve been featured by mainstream artists. I’ve been featured by Kida Kudz and we have a track together called Cherry Mango. I’ve done one with Runtown, that one is called Mama Told Me. I have another one coming up with a cool mainstream artist between February and March. I also did something with The Cavemen, although I wouldn’t necessarily put them in the mainstream category, however, we have a song together called Biri. I am always open to features, as long as I like the music and feel like I can contribute. As far as me featuring artists goes, that is slightly more difficult because when I write, I don’t write for space for other people, I write for the band and myself. And when it goes into the process of mixing and really designing the track for studio and radio, it is always difficult to find the person that I think can contribute to the sounds of the album. But with this EP that I am releasing soon, I hope that I can find people to jump on it in some way, even if it’s not the common way of getting a 16-bar verse. Something different.

You were named as a voting member of the Recording Academy. How excited are you about keeping the genre your grandfather pioneered alive?

I was just happy that there were as many voting members from Nigeria and Africa as possible, just to show that we can be represented in the Recording Academy—especially in categories like jazz and classical music.

It does feel like we are sidelined and it doesn’t do justice to what we do.

As a musician myself, the categories that I respect the most are usually the categories that don’t get TV time and people think are the lower categories like Best Jazz Performance and Best Jazz Album, those are my favourite categories, but they don’t get the limelight. What is important is that I can put a voice for Nigeria in those categories.

How do you address comparisons between your music, your dad’s, and granddad’s? My dad is not like Fela at all, the music is very different, and just like that, my music is very different from both of their music. I hope that people can listen to us differently and not feel the need to find the best because when you do that, you are putting toxins in a very pure form of art. You are trying to poison it by putting your impression on it, whereas you are a consumer, not the producer.

What would you say is the biggest lesson that music has taught you?

Patience and expression. The tediousness of practicing the same thing over and over again has made me very patient, but also the cathartic feeling of being able to express yourself as loudly or quietly as you want with no words necessarily has made me a very expressive person. So I can be patient but also very expressive.

You come from a very powerful Nigerian household, known for its contribution to the country’s development in the form of art and activism. Would you call yourself an activist as well?

No, I avoid that word as much as I can. My dad for instance wrote a lot of political music under military regimes, which in my opinion was very risky on my life [laughs]. Fela did it, my dad did it, my uncle Seun also did it. I am very concerned about politics and I’m learning from my predecessors. I believe Nigeria is worse off; mentally, culturally, politically, economically and even our climate is worse than it was during the 80s and 70s. I understand that leadership is by far the most powerful form of change if you think about it because to look at somebody and depend on that group of people to bring about change is by far the most reliable force of progress. But when that leadership fails, we can either continue to be expectant of that form of leadership or we can take on the responsibility ourselves.

Let’s talk about your grandfather’s exploits and your trajectory. Fela was one of the most sampled artists of all time. Anyone would be considered hugely successful if they had half the impact he had. Does that sort of put pressure on you to live up to the hefty standards he created?

Absolutely not. I’ve been very lucky. This goes back to my dad as well, he has taken the brunt of the weight. That pressure, that burden, the ‘all eyes on you’ to see if you can do it or not, he did it. What he has done is he has broken the cycle, he shattered what people told him wasn’t possible. And so what people now have for me is positive expectations. It wasn’t the case for my dad, it was mostly “what can you possibly do? Your father has done it all, what is left to do?” for him, whereas for me it is “third generation, let’s see what you can do”. People are giving me shows because of my dad. Nobody was giving my dad any opportunity because he was Fela’s son.

How do you manage to stay grounded?

It’s family for me. It’s the people around me. I think above the music and all of the legacies, I’ve been blessed with a very strong core group of people and those people have made me wise enough to understand what is good and bad. For example, I’ve never been the kind of person to be in need of company, so that means solitude was very easy if I had to do it, companionship was also very easy if I had to do it. But I had a core group of people, I had my dad, aunty Yeni, mum, Rolari, and then I had my brothers Dami, Kwame, and Muhammed. So every time I knew there was any kind of difficulty or challenge, I always knew I had a positive home to return to.

The genre that you do is not mainstream. How do you intend to market it to people from your generation who wouldn’t listen?

If you are a creative and you’re not aware of your times, and you choose to not reflect your times in your music artistically and lyrically, if all you’re going to do is try and recreate what has been done, that is not creativity, that is copy and paste. As a creative, it is important to me that I feel like I do something original that is true to me but to be intentional about the people that I want to listen to my music. Which is what I said about For(e)ward; it was me just doing whatever I wanted to do. It was my first body of work and what you people think is your business [laughs]. I would just write, play, have fun, experiment and not let any track sound like any other track. Whereas now I’m very intentional about people and how they feel about the music. So anytime I write a song now and I play it, I’m always asking how they feel about it, do you like it? Because when I write, I look for common ground as a musician, where I don’t use my knowledge to be egotistical in my sound.

How would you describe your style?

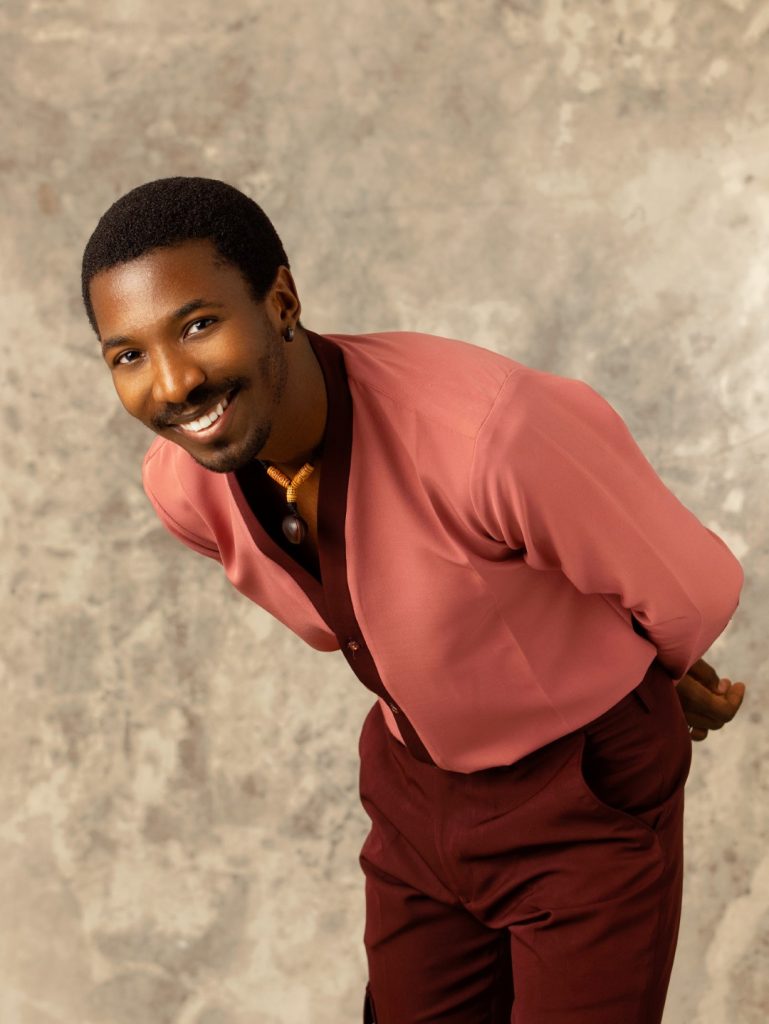

My style is entirely Braimien. It is a clothing brand owned by my friend and stylist, Dolapo Bello. I can’t dress myself, I have zero fashion sense. It’s mostly because I was never a social person, so I never went out to see what people were wearing. I was very happy with inheriting my father’s clothes. So when I came back [to Lagos], it was then a matter of “Mádé, you are about to start standing on your own in public, you better start looking the part.” So my brother, Dami, introduced me to Dolapo. The first 20 minutes of our conversation was ideological and intentional and less fashionoriented, and I just instantly knew that anything that he produces I’m fine with it.

You rehearse a lot and spend most of your time making music. When you’re not doing that, how do you relax?

I play FIFA—I am probably the best in the world [laughs]. I play with my dad actually, he’s very good as well. I spend time with family, my partner and friends. I watch Netflix and play football, that’s it. My life is not that eventful. I don’t go on holidays, at least not yet [laughs].

When is the next project unveil?

Hopefully February or March. It will have five tracks, each track will be different and lovely. It is not me playing all the instruments this time, I made sure that the band is involved totally, but I still compose everything myself. I’m working with my longtime brother, Quddus “GMK” King, who is a producer. We are putting a lot of ideas into the music. It doesn’t have a title yet, we just know that it is going to drop soon. But with COVID-19, you never know.

How often do you play at the New Afrika Shrine?

Every Wednesday from 6pm to 8:30pm. Just like how my dad decided to open his rehearsals to the public for free, I’ve also decided to do that. So I share new music and then meet and greet after. But the performances which are usually once a month, are announced separately. We will start that in February

Photography: Gift Eghator @grapghedbyblue

Luminescent “EM” two-piece in Onion Pink and burgundy mix: Braimien (@braimien)

Stylist: Dolapo Bello of Braimien (@braimien)

Creative Direction Onah Nwachukwu @onahluciaa

Assisted by Tilewa Kazeem @tillyofourtime

Self-identifies as a middle child between millennials and the gen Z, began writing as a 14 year-old. Born and raised in Lagos where he would go on to obtain a degree in the University of Lagos, he mainly draws inspiration from societal issues and the ills within. His "live and let live" mantra shapes his thought process as he writes about lifestyle from a place of empathy and emotional intelligence. When he is not writing, he is very invested in football and sociopolitical commentary on social media.