Our Streaming Culture: Evolution Of Arts And Entertainment Consumption

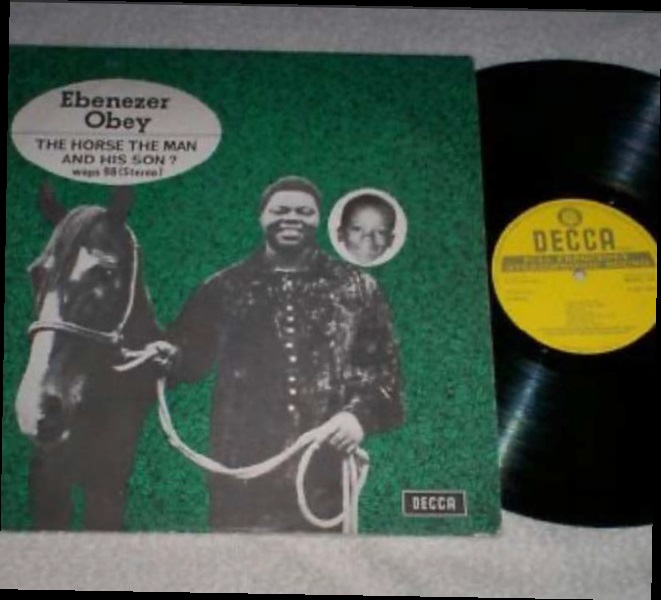

Since we all can remember, the arts and entertainment industry has always been lauded as one that has experienced consistent growth. Technology has changed a lot, and it goes without saying. Once upon a time, before cloud spaces took on a meaning other than ozone layer conversation, before streams were not mistaken for anything apart from a water body, things were done differently. Those were the innocent days of unabashed piracy when most Nigerians consumed films in assorted DVD collections and music from vinyl and mixtape CDs. Our first interaction with digital streaming as a concept was downloading songs from bootleg websites that slap their producer tag haphazardly on the track as though they helped create it. Things are a lot different nowadays. Today, with the internet’s availability and a monthly subscription, anyone can easily access content globally, which has changed the game tremendously. But to what degree? Are there cons to the obvious pros? What does the year hold for the entertainment industry as far as quick exportation of indigenous Nigerian content through streaming goes?

The Double-edged War On Piracy

For so long, the entertainment industry in Nigeria fought a long hard battle against piracy. Copyright infringements became normalised as pirated copies of films (during the home video era) and songs were readily available even on the day of release. With no inkling of how to curb this epidemic that prevented creators from their maximum revenue, streaming services came just in time to phase out VCDs and DVDs. On the movie front, the battle against piracy seemed to have been damned as a lost cause as stakeholders within Nollywood became bereft of lasting solutions. Although it was a similar conundrum for the music industry, the war on piracy was more complex than with films. As digital on-demand song streaming and download became commonplace, directly replacing physical CDs, it quickly became a tool that aided the propagation and reach of the industry. Despite earning nothing from bootleg websites and losing revenue because of them, music artists never really raised the alarm against piracy to play the long game—use it as a quick, free distribution and marketing tool.

Streaming Impact On Nollywood

One of the most significant effects of the movie streaming market was on the DVD market, which saw a sharp decline in popularity and profitability due to the widespread adoption of online content. The rise of media streaming caused the downfall of many DVD rental companies, especially in Lagos, Nigeria. Over in the United States, shortly before its breakup from video streaming, Netflix’s DVD by- mail service boasted more than 16 million subscribers, a number that has now dwindled to an estimated 1.5 million subscribers, all in the U.S., based on calculations drawn from the company’s limited disclosures of the service in its quarterly reports. On the other hand, their streaming services have 223.09 Million Subscribers as of the third quarter of 2022.

The Nigerian film industry is revered globally as one of the most valuable in the world. Regarding the quantity of production, Nollywood has always been in the top 3 conversations alongside India’s Bollywood and America’s Hollywood. Since the 2010s, however, the number of released Nollywood productions has significantly reduced as filmmakers shifted the focus to the production quality required by the two most likely destinations—the cinemas and digital streaming platforms. Today, the film industry as we know it has been able to churn out truly world-class productions because of the streaming culture.

Impact On Music And The Streaming Farm

For the music business, the past half-decade has seen a resurgence. Revenue from recorded music sales has increased each of the last seven years, following the decades-long lows in income in the early 2010s caused by online piracy and shifts away from physical record sales. This sudden and rapid growth has been driven by the popularity of streaming services such as Spotify and Apple Music. During the pandemic year, 2020, streaming services yielded $13.4 billion globally, making up 62.1 percent of total music industry revenue. The music industry’s shift towards an on-demand streaming model has been heralded by many as a positive change. Streaming subscriptions allow music fans to listen to more music than ever before and, in most cases, are more affordable than purchasing full albums (the average paid streaming service subscription costs about $10 per month, and many offer free, ad-supported versions of their service). There is no doubt that the Nigerian music industry has benefited immensely from this.

The rise of Afrobeats is very synonymous with the popularisation of streaming culture. It is no surprise the role of technology as a surefire amplifier. That is not to say the music industry wasn’t doing just fine with exporting its best offerings because it was. However, the speed at which it is happening nowadays is unprecedented. Music promoters, for instance, have since had their work cut out as they no longer have to keep track of how many physical CDs are burnt for the distributor and the usually tedious inventory that follows. Before digital streaming, it was almost impossible to survive in the industry as an independent artist.

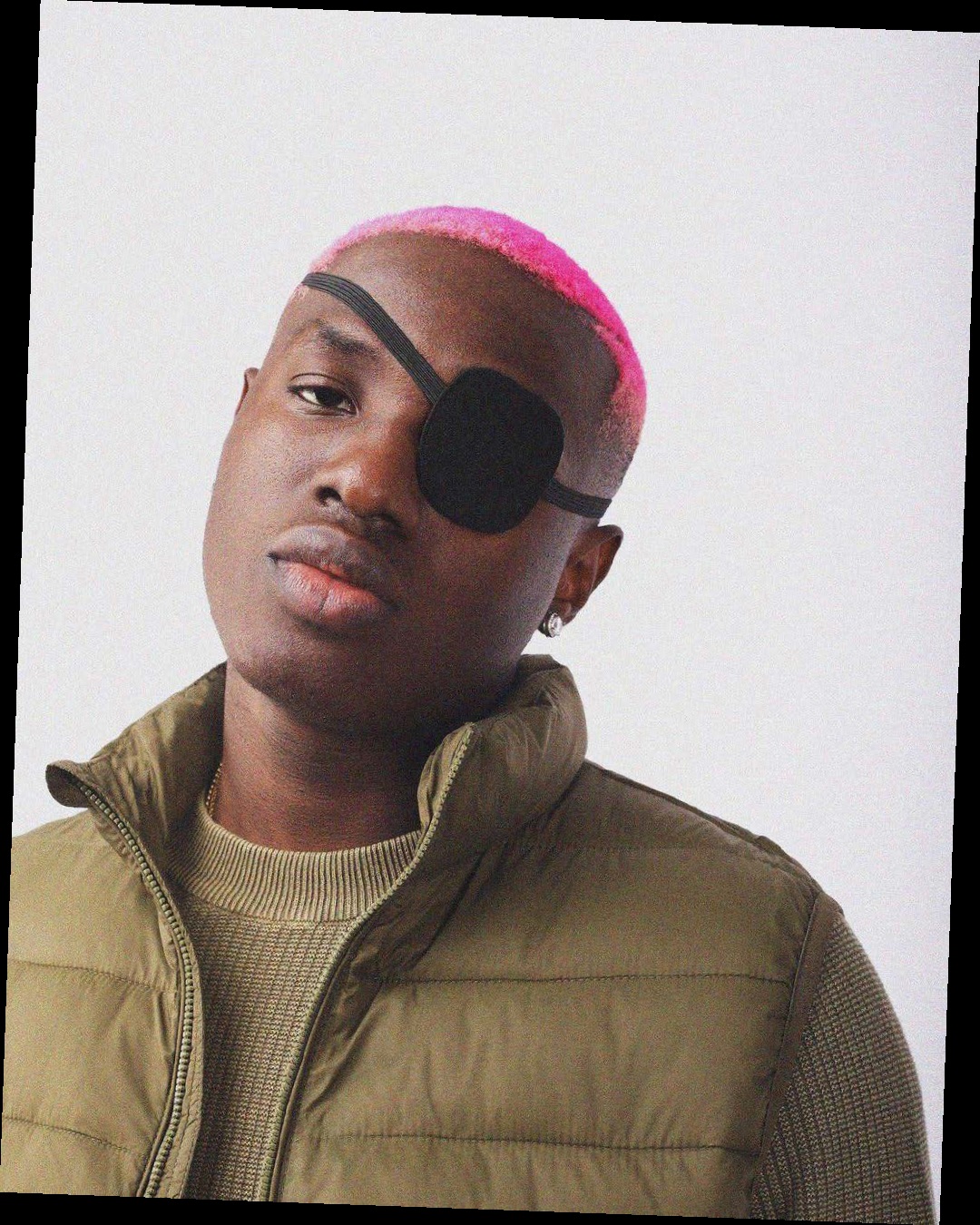

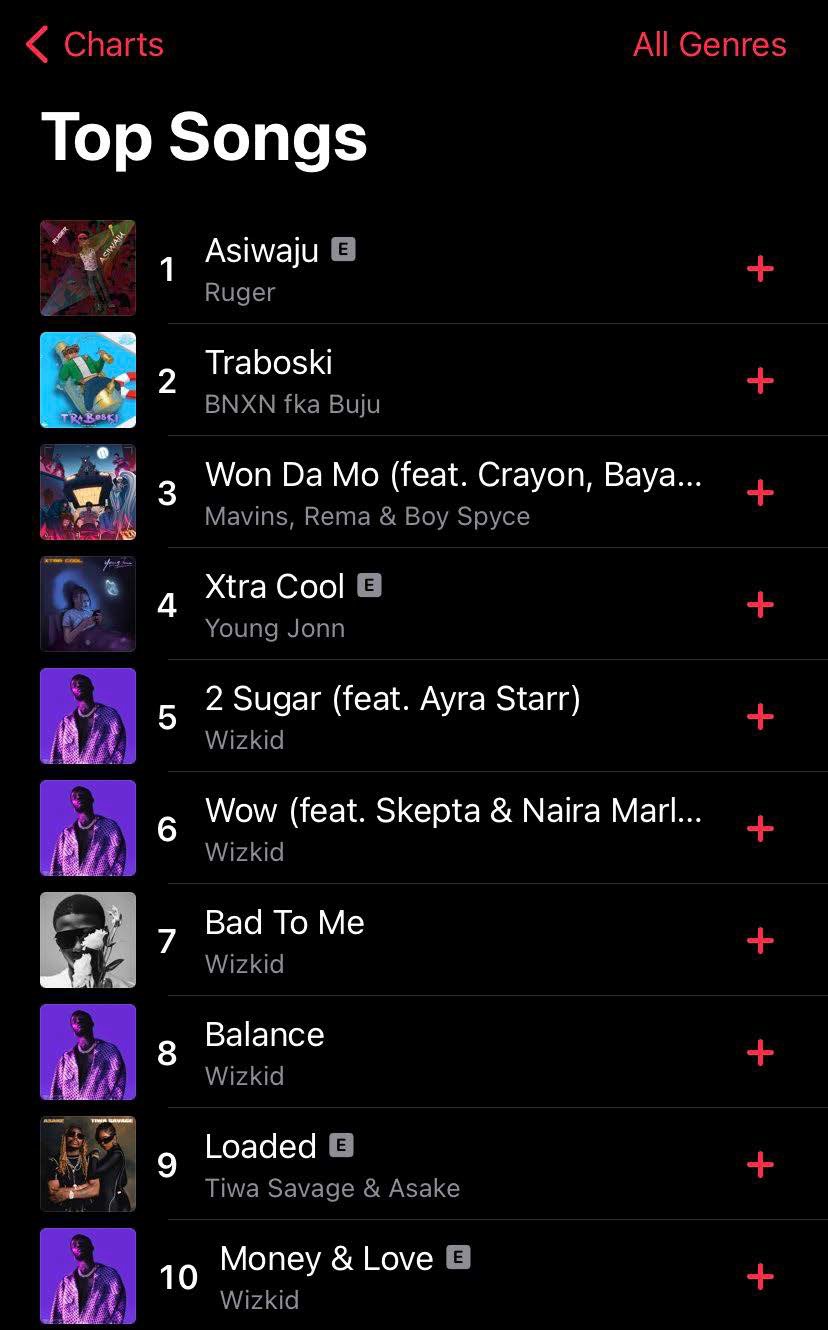

Last year, music artist, BNXN (formerly known as Buju), in a vicious back and forth with his colleague, Ruger, impugned him of doping his digital streams. In one of his social media posts, BNXN accused Ruger of using streaming farms to illegally grow his streaming numbers, which led to more royalties and other benefits. “There are streaming farms in Nigeria now. A room where your label bosses pay money to get your songs up by automation, no real fans, no real people, just a facade. Y’all make the people who really work for this bleed, and your day is coming,” BNXN said.

Streaming farms are services created to illegitimately boost the number of times a song is listened to through the use of software Bots or using many phones. After the brawl and exposure of the streaming farm, top Nigerian music journalist, Joey Akan discusses the blackmarket-esque operation in a series of tweets.

“Apple Music Top 100 has become a marketing tool for Nigerian musicians, not an independent curation of the country’s listening habits. Apart from bragging rights and screenshots, people rig streams to climbing up there for the public attention it brings to the record.”

Speaking on why labels use streaming farms, Akan said: “That marketing firm that offers you a range of streaming numbers for money or guarantees you the number 1 spot. What do you think they do? Move from house to house and ask people to politely click on your music? Or break the bank on ineffective ads? Everyone goes to the farmland.”

We Are Late To The Party

Over the past couple of years, the creative industry has welcomed all sorts of campaigns from digital streaming platforms. It is clear to see why entertainment powerhouses come to pitch their tents here. From Amazon Prime’s launch of a localised version of its streaming service to Spotify’s get-together of creatives, last year especially fanned the flames of the inherent streaming war that has seen them (streaming platforms) in a perpetual digital tussle for our attention since the pandemic hit.

It is a streaming economy globally, not just in Nigeria. In fact, Nigeria is quite late to the party. Last year, Disney+ announced an expansion into 42 countries across Europe, the Middle East and Africa, with South Africa, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Morocco, and Egypt making the list. On paper, it seems logical that an obvious market like Nigeria would be first in line for this kind of development, but the situation is more complicated than that.

Although Nigeria’s economy is arguably bigger, it is unstable, has outdated infrastructure, and has low purchasing power. On a global scale, only South Africa—of all African countries—makes Netflix’s top 50 countries, with over 350,000 subscribers. Nigeria did not make the list, with Malta rounding it up at 30,200 subscribers. The gulf in orderliness between Nigeria and South Africa is not worthy of a whole paragraph; it is visible to the visually impaired. They have the most advanced TV rating system in Africa, allowing companies to track consumer behaviour more accurately, and their economy, although not the largest, is more stable. It also helps that they have a better download speed, according to cable.co.uk, at 28.62 Mbps (Nigeria is at 15.37 Mbps average download speed) which means a faster Internet connection.

Currently, three global streaming services have made their debuts in the African market: Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, and Disney+ joining an already saturated pool of local players such as MultiChoice’s Showmax, Arise TV’s Arise Play, Access Bank’s Accelerate TV, VideoPlay, and Safaricom’s BAZE.

According to projections, Africa is expected to hit 26 million video-on demand subscribers by 2026, which explains why we are seeing an influx of streaming platforms coming into the continent. Alas, it is a classic capitalistic ‘scratch-my-back-I scratch- yours’ bargain.

Self-identifies as a middle child between millennials and the gen Z, began writing as a 14 year-old. Born and raised in Lagos where he would go on to obtain a degree in the University of Lagos, he mainly draws inspiration from societal issues and the ills within. His "live and let live" mantra shapes his thought process as he writes about lifestyle from a place of empathy and emotional intelligence. When he is not writing, he is very invested in football and sociopolitical commentary on social media.