Embracing Equity: Equality Or Equity, What Delivers The Fairest Outcome?

Throughout human history, equality has been central to every social justice fight. Across countries and continents, there is a constant tug of war over equal rights for every individual. On the gender front, equality struggles the most to take a definition of its own and ultimately get a resolution. According to the Oxford dictionary, equality is the state of being equal, especially in status, rights, or opportunities. Make no mistake; this is the morally ideal modus operandi to imbibe by. Maybe not in status as society is firmly rooted on the pedestal of capitalism, but in rights and opportunities, we should all strive for unequivocal equality. But it is not as easy as it sounds.

Common sense deduces that man and woman are not equal at the very core of their existence. The highly different experiences we live through shape our perspective of life and can put us on two very unequal trajectories. For instance, girls must learn about adult cleanliness during their preteen years because menstruation and puberty make them grow faster than boys. This could also explain why women populate the care industry; they have been learning to care for themselves and others since childhood. For boys, especially during puberty, their testosterone growth is rapidly fostered by the glaring physical body changes and a society constantly reminding them that they are responsible for providing and protecting. On this other end of the spectrum is an explanation as to why men dominate the military industry. As we ascribe meaning to gender equality, it is important to do so with the utterly logical resolution that perhaps equal opportunity doesn’t always translate to equal outcomes. And so, society has been caught a few times playing with the thoughts of abandoning the fight for an egalitarian society for equity.

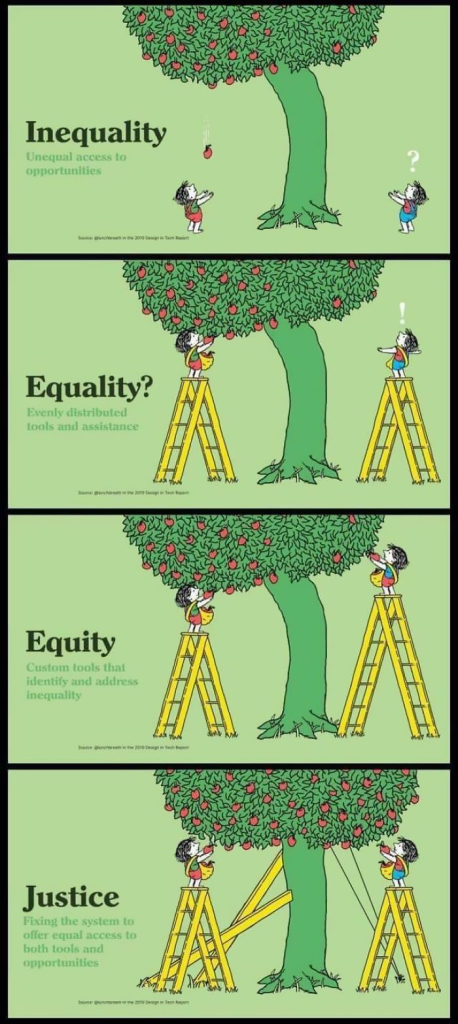

In the context of societal systems, equality and equity refer to similar but slightly different concepts. While equality generally refers to equal opportunity and the same levels of support for all segments of society, equity goes a step further and refers to offering varying levels of support depending upon the need to achieve greater fairness of outcomes. This is an important topic as it provides insight into the gender pay gap. One could argue that it exists because there are more men in STEM fields—an umbrella term used to group the distinct but related technical disciplines of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics—than women. So how do we solve that conundrum? How do we balance out the ratio of men and women in construction engineering?

Data suggests that, on the contrary, gender differences across six key personality traits—altruism, trust, risk, patience, and positive and negative reciprocity—increase in richer and more gender-equal societies. Meanwhile, in societies that are poorer and less egalitarian, these gender differences shrink. The study was largely focused on egalitarian Scandinavian countries where boys and girls are raised on the default consciousness of equality. The result of that? More men in STEM fields and more women in care positions. Speaking on that study, renowned, controversial Canadian psychologist, Jordan Peterson said, “first, men and women are more similar than they are different. This is true, cross-culturally. Even when men and women are most different—in those cultures where they differ most and along those trait dimensions where they differ most—they are more similar than different. However, the differences that exist are large enough to play an important role in determining or at least affecting important life outcomes, such as occupational choice.”

According to Peterson, “where are the largest differences? Men are less agreeable (more competitive, harsher, tough-minded, sceptical, unsympathetic, critically-minded, independent, and stubborn). This is in keeping with their proclivity, also documented cross-culturally, to manifest higher rates of violence and antisocial or criminal behaviour, such that incarceration rates for men vs women approximate 15:1. Women are higher in negative emotion or neuroticism. They experience more anxiety, emotional pain, frustration, grief, self-conscious doubt and disappointment (something in keeping with their proclivity to experience depression at twice the rate of men). These differences appear to emerge at puberty. Perhaps it’s a consequence of women’s smaller size and the danger that poses in conflict. Perhaps it’s a consequence of their sexual vulnerability. Perhaps (and this is the explanation I favour) it’s because women have always taken primary care of infants, who are exceptionally vulnerable, and must therefore suffer from hyper-vigilance to threat.”

As always, research and scientific findings are largely based on averages and percentages, at the risk of generalising. If we put aside the “not all men” rhetoric and “every woman is different” obvious tropes, we might get to the bottom of this fight for equality, which has stared right at us for so long—equal opportunity doesn’t always mean equal outcome, so maybe it is time to embrace equity.

Self-identifies as a middle child between millennials and the gen Z, began writing as a 14 year-old. Born and raised in Lagos where he would go on to obtain a degree in the University of Lagos, he mainly draws inspiration from societal issues and the ills within. His "live and let live" mantra shapes his thought process as he writes about lifestyle from a place of empathy and emotional intelligence. When he is not writing, he is very invested in football and sociopolitical commentary on social media.