Equal Pay: The deafening silence lingers

Humans have had several problems since the first person was created. As time passed, we have fixed one issue or the other; this defines the human experience. One subject matter however looks unsolvable: equality. For religious people, the disparity can be traced back to the beginning of creation. One doesn’t have to look too critically to see that we have never been equal, hence we would have solved the majority of our problems. Topics such as racism and gender-based violence, for instance, wouldn’t afflict us today if we see the next person as equal to us, with the right to enjoy the same basic opportunities as we do. As we strive to achieve a middle ground in all of our negotiations for parity, one dilemma remains unresolved, and it happens at the workplace where we essentially make our livelihood.

Workers around the world look forward to payday. A paycheck may bring a sense of relief, satisfaction, or joy, but it can also represent an injustice — an expression of persistent inequalities between men and women in the workplace.

Globally, the gender pay gap stands at 16 per cent, meaning women workers earn an average of 84 per cent of what men earn. In racially diverse countries, black women, immigrant women, and women with children are further down the remuneration pecking order.

Global Impact

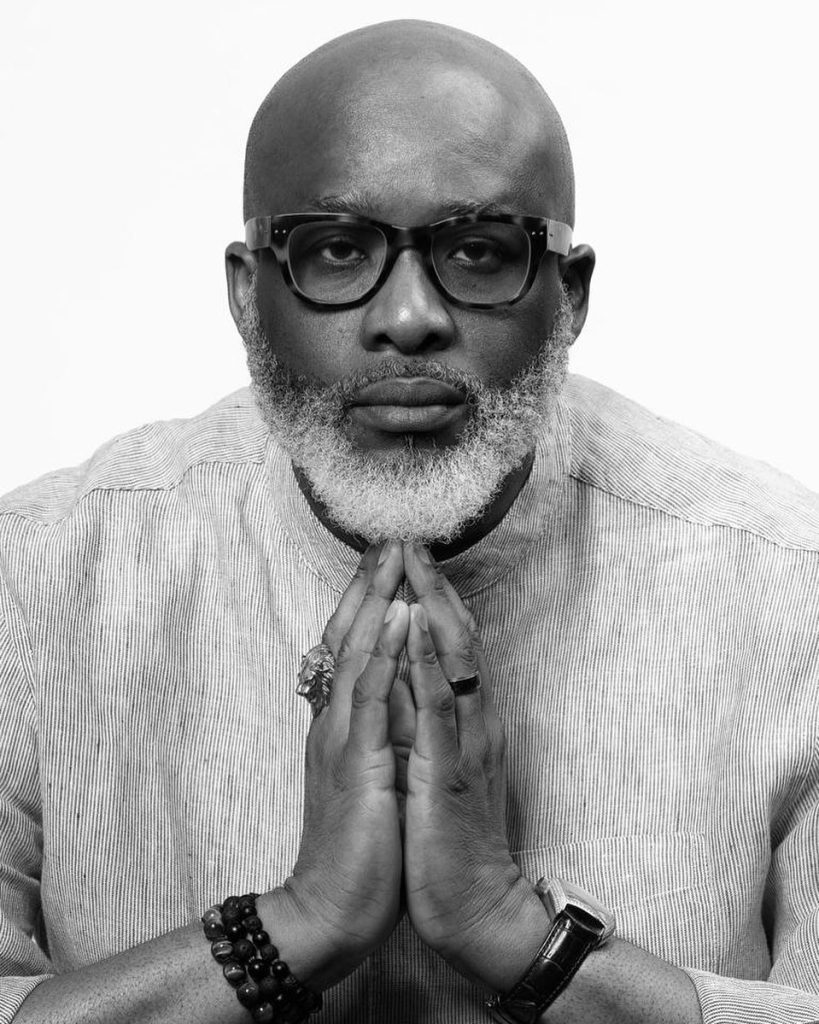

Speaking about the gender pay disparity, Chidi King, Director of the Equality Department of the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), dives deep into the ideologies which helped form the quagmire.

“The global gender pay gap is an expression of persistent inequalities between men and women in our societies and our places of work. The social and cultural norms that broadly cast men’s roles as decision-makers and women’s roles as carers, play a significant part—not only in terms of the type of paid work into which women are channelled—but in terms of how that work is valued and remunerated.

Chidi King, Director of Equality Intenational Trade Union Confederation – kevin cooper photo

When women enter the formal labour market, their paid work and their role as workers are often seen as subsidiary or supplementary to their principal role of “homemakers”. This in turn impacts how women are paid. Even where women have equivalent or better qualifications than men, their skills are not valued the same as men’s and their career progression is slower,” she explained.

“The world of work as we know it is still generally structured around the male “breadwinner” model, with long and rigid working hour arrangements. As women become mothers, they bear the “motherhood penalty”—to balance family responsibilities and paid work, women accept part-time, casual or underpaid jobs, or work in the informal economy. In pregnancy, they may also face discrimination, which can lead to them being dismissed, harassed out of the workforce, or demoted on their return. Taking time out to care for children also slows women’s career progression,” she concluded.

The Corporate World

In the corporate world, a wage structure is maintained. This is the hierarchy within a company that sets the amount each level of employment is paid and what benefits each level is due. Over the years, there has been a gender wage disparity in the workforce. In some instances, the basic salaries of a man and woman are the same, but the other components such as allowances and prerequisites vary to favour the man. This is still ongoing to date.

To get a sense of the impact of that in today’s corporate world, we spoke to Lanre Olusola, Africa’s foremost Life Coach and Cognitive Behavioral Psychologist who is the Chief Catalyst at the Olusola Lanre Coaching Academy (OLCA) and also an Executive Director of Ebony Life TV.

Lanre Olusola

When asked about his views on the social injustice, he responded; “I think we need to, first of all, understand the world of work and in doing that, we realise that there’s an objective, vision and goal which are time-bound. Now, to be able to achieve those goals within the stipulated timeline, you need a combination of competence and skill and this is what employers should pay for; it should have nothing to do with gender. If we begin to look at competencies, you will realise that men and women went to school through the same admission process, there were no special cut-off marks for women. They studied the same course for the same duration in class, got tested on the same exams, graduated with the same grades, and went through the same rigorous interview process to get the job. Now when they were employed, there was a job description that was set for the role they applied to and they both qualified for. So why should a man think that he should be earning more than a woman?”

A popular argument has been made over time to support the pay inequality, referencing man-hours and the proposition that men can work more hours than women, buttressing it with women’s unavailability when they have to yield nature’s call in the form of pregnancy and what comes after it. Olusola thinks otherwise. When asked how big of an impact this ideology is on the pay disparity, he responded, “Women can multitask more than men, so it’s not about the amount of time spent on tasks, it’s the efficiency in meeting deliverables. Also, the world of work has changed. Nowadays, people work virtually, so how do you measure the actual time they put in? Performance appraisal should always be deliverable-based, as opposed to man-hours, this is measurable and time-bound. One person could deliver a task in five hours whereas it took their colleague ten hours on the same task. So who has done more work? The argument of time to belittle a woman’s input is nonsensical. Efficiency is all that matters.”

We then shifted the conversation on men’s involvement to discuss what roles they play in ensuring that the gap closes up.

“My educated guess is that there are more women in Human Resources than men. In my opinion, because of that, they have the power to change the policy. I think they need to establish equality through a performance management system. Set up this equitable system and get management to sign off on it. Every management wants productivity that reflects in the revenue, it doesn’t have to be about gender,” he said.

When asked how it was possible to convince a male Managing Director, who doesn’t subscribe to equal pay, to sign off on the performance management system, he responded, “Don’t present it as a gender policy because quite frankly, that shouldn’t even be brought up in the conversation. It should be presented as an organisational policy. Don’t play the gender card. Propose a performance management system that’s based on quality delivery within a timeframe. It affects and benefits both men and women, that’s how you create equality. Court sentences for felonies, drivers licence applications and restaurant prices are not given to people based on their gender, so why must work remunerations be? We must create neutral workplace policies.”

Oftentimes, men who champion women’s causes are seen as effeminate. This goes beyond equal pay and to the broader scope of feminism; men who are female allies are considered weak. We discussed this stigma to get Olusola’s view of it. “When you think about it, I’m making a case for men just as much as I’m making for women; I’m not biased, I’m making a reasonably intelligent performance case that will benefit men and women. The only people it won’t benefit are those who can’t perform because the system will root them out and put them on probation. However, if a man considers putting an equitable system in place as weak, it is he who needs to change his perception because it will benefit him if he was a performer. People like that are myopic and need to change their perception of life.”

The Entertainment Industry

Another industry that has seen claims of a wage disparity stem from gender bias is the entertainment scene. Globally, female actors complain about earning significantly less than their male counterparts. To get a perspective of this, we spoke to experienced Nollywood actress, Yvonne Jegede.

Yvonne Jegede

We asked if she had ever been in the same position as a man and earned less. She replied, “Right now, I’d say no. In the past, yes but it has to do with your status. As I progress in my career, I’m earning my respect. My business (the entertainment industry) is different when compared to the typical nine-to-five; it has to do with your brand. So if someone is earning more than me, it’s only because the person has more power and clout to push themselves farther than I would be able to. The wage structure is heavily dependent on your fanbase and the level of respect you can command amongst your colleagues.

In Sports

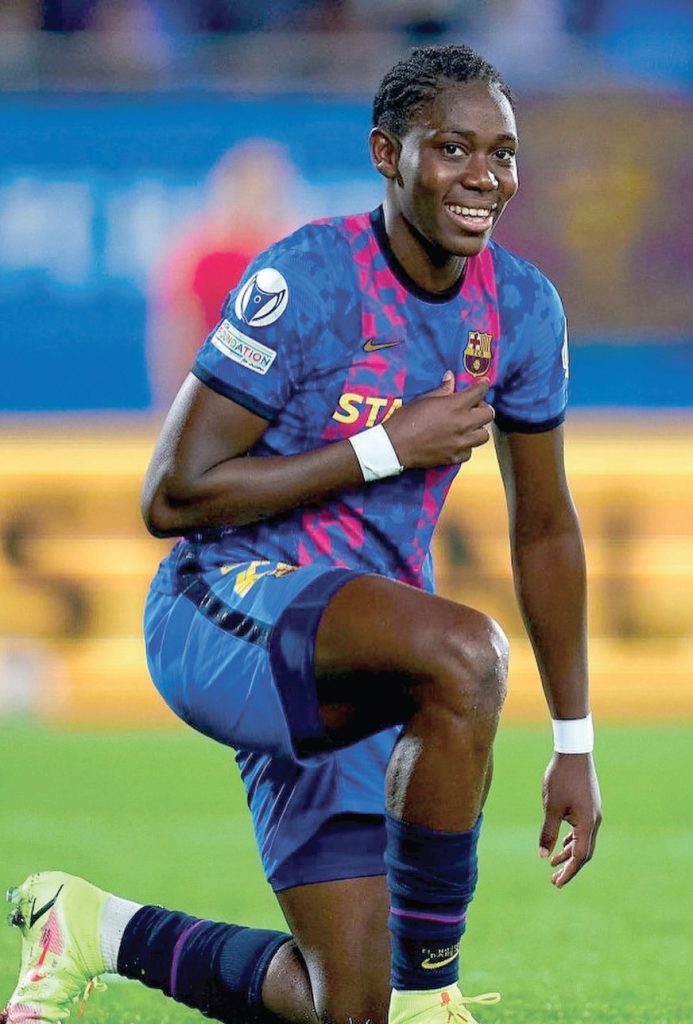

In football, women have been protesting pay inequality in recent times, most especially the United States Women’s National Team. Having won a staggering number of international tournaments, much more than the men’s team, they get paid a fraction of what their male counterparts earn.

In our International Women’s Day edition, we spoke to one of Africa’s top footballers, Asisat Oshoala, about inequality in football.

When asked how she has been able to navigate obstacles of race and gender as a female athlete? She replied, “Equality in professional football is a difficult conversation to have because it really is a situation where the guys get more TV rights and publicity, resulting in more endorsements and everything else. For now, I am happy to be here in the club I love (Barcelona), repping Nigeria and hopefully inspiring young female hopefuls back home.”

Asisat Oshoala

Our Constitution

According to the constitution, the state must ensure there is equal pay for equal work without discrimination on account of sex, or on any other grounds. However, no implementing legislation has been enacted so far. A Labour Standards Bill, submitted in the National Assembly in 2008, had provision on equal pay for equal work, however, it has not been passed.

This conversation has been reduced to murmurs and going by antecedents, it wouldn’t be far-fetched to assume that it has been thrown out. In a country like ours where every social justice issue takes a backseat to every other talking point, perhaps this could be a golden opportunity to make a global statement as not too many nations have passed the equal pay for equal work bill in the world.

The History

Before the Industrial Revolution in Europe and the United States which was the transition from hand production to new manufacturing processes involving chemical and iron productions, the development of machine tools and the rise of the mechanized factory system, gender roles have been defined.

This was at a time pre-technology, so most of the labour required physical power which gives men a biological edge over women. Society quickly shaped up around the arrangement that is the patriarchy. Men were going out to work construction jobs, women stayed back at home with the children for domestic roles.

The Industrial Revolution led to an unprecedented rise in the rate of population growth and this only meant that there are more children to take care of, further relegating the number of women in the workforce, conversely increasing the men’s wages because they then had more mouths to cater to.

Eventually, as wage labour became increasingly formalized, women joined men in the factories. They were often paid less than their male counterparts for the same labour, whether for the explicit reason that they were women or under another pretext.

The concept of equal pay for equal work was first put forward as a part of first-wave feminism, with early efforts being a product of nineteenth-century Trade Union activism in industrialized countries: for example, a series of strikes by unionized women in the UK in the 1830s.

As a consequence, after the Second World War, trade unions and governmental leaders in industrialized countries gradually came to embrace equal pay for equal work. Well, not entirely but that was the beginning of an ongoing conversation to date.

The Definitions

Equal pay means that all workers have the right to receive equal remuneration for work of equal value. While the concept is straightforward, what equal pay actually entails and how it’s applied in practice has proven to be difficult. Often labelled wrongly, equal pay and equal work mean different things in several contexts.

Equal Pay

Equal pay applies to all contractual terms, not just pay. This includes:

- basic pay

- non-discretionary bonuses

- overtime rates and allowances

- performance-related benefits

- severance and redundancy pay

- access to pension schemes

- benefits under pension schemes

- hours of work

- company cars

- sick pay

- fringe benefits such as travel allowances

- benefits in kind

Equal Work

On the other hand, there are three kinds of equal work: Like work, work rated as equivalent and Work of equal value.

Like Work

’Like work’ is work that is the same or broadly similar. It involves similar tasks requiring similar knowledge and skills, where any differences are not of practical importance.

A difference in workload doesn’t itself prevent a ‘like work’ comparison unless the increased workload represents a difference in responsibility or other difference of practical importance.

These examples have been judged to be ‘like work’ by the courts:

- A woman preparing lunches for directors and a man preparing breakfast, lunch and tea for employees.

- Male and female supermarket employees who perform similar tasks requiring similar skill levels, although the men may lift heavier objects from time to time.

Work Rated as Equivalent

‘Work rated as equivalent’ has been rated under a valid job evaluation scheme as being of equal value in terms of how demanding it is, including effort, skill and decision making. Jobs involving dissimilar tasks may be rated as equivalent.

For example, the work of an occupational health nurse might be rated as equivalent to that of a production supervisor when components of the job such as skill, responsibility and effort are assessed.

Work of Equal Value

‘Work of equal value’ is not like work and has not been rated as equivalent, but is of equal value in terms of demands such as the effort involved, skills necessary to do the job and decision-making that is part of the role.

In some cases, the two jobs may appear broadly comparable, such as a female head of personnel and a male head of finance. More commonly, entirely different types of jobs, such as manual and administrative, can turn out to be of equal value when analysed.

Examples of different jobs which have been ruled to be of equal value by the courts include:

- Clerical assistant equal to warehouse operative

- Canteen workers and cleaners equal to surface mineworkers and clerical workers

- School nursery nurse equal to local government architectural technician

- Head of speech and language therapy service equal to the head of hospital pharmacy service

This does not necessarily mean that jobs with these job titles or similar will always be of equal value to each other in every organisation that uses the same titles.

Self-identifies as a middle child between millennials and the gen Z, began writing as a 14 year-old. Born and raised in Lagos where he would go on to obtain a degree in the University of Lagos, he mainly draws inspiration from societal issues and the ills within. His "live and let live" mantra shapes his thought process as he writes about lifestyle from a place of empathy and emotional intelligence. When he is not writing, he is very invested in football and sociopolitical commentary on social media.