Ali Baba – Being Funny Is Serious Business

Humour is one of the prevalent elements of our social interactions. No matter the mood or emotions, good humour has been prescribed as not just a psychological band-aid that helps ease human interactions but also a tool for social change.

But before the commercialisation of the funny business here in Nigeria, before you could go on the internet and spend practically a lifetime consuming comedy in pint-sized clips, there was a time when standup comedy as an art form was not a mainstream segment of the entertainment industry. At the time when traditional musicians were invited alongside their band members to play their well-composed choruses at functions, when stage actors thrilled thespians acting out well-written plays, Atunyota Alleluya Akpobome, widely known as Ali Baba, a professional heckler, began to map out the professional pathway for comedy, laying the foundation of the art of telling jokes to crowds as a service worthy of building a career on.

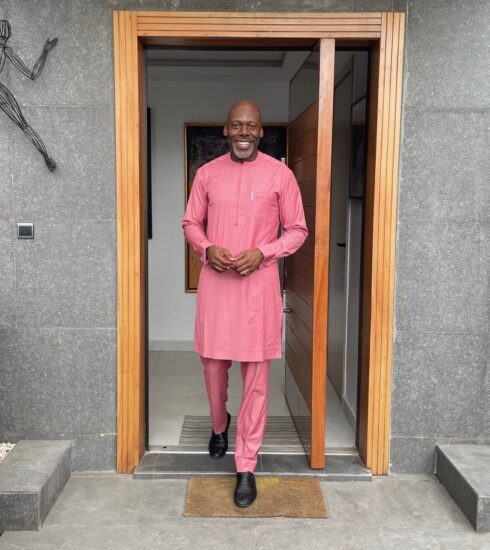

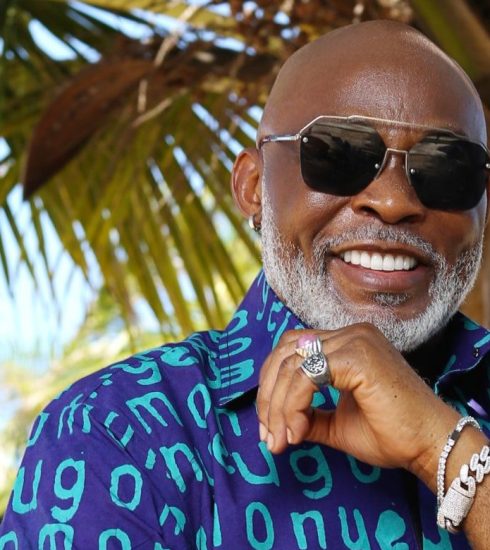

Thirty-eight years later, the veteran, regarded nationwide as the godfather of Nigerian standup comedy, spoke to DOWNTOWN’s Kehindé Fagbule in the comfort of his office, sharing his experiences creating a food chain and climbing right to the top of it. His unrivalled sense of humour was evident throughout the lengthy conversation as the recently-turned 58-year-old veteran discussed everything from touring campuses in the late ’80s to maintaining his status quo as one of the biggest voices in Nigerian entertainment’s history.

Some people may say you pioneered standup comedy in Nigeria. Can you share the story of how you got started in comedy? What inspired you to pursue a career in making people laugh?

It will look like I pioneered, but I think it would be appropriate if you said I give it some leverage because you could count people who were comedians, maybe not standup comedians. At the time between 1983 and 1985, Bendel Radio had people like Jude Ewewe, Patrick Doyle, Bisi Olatilo, and John Chukwu. Although they practised comedy, they were not full-fledged standup comedians. With time, when I came on the scene, I discovered that I needed to map out the real standup dynamics to practice just like Eddie Murphy and the likes. So I would say it was the application of what I was doing that then became different from what they were doing before I came on the scene.

What was your first-ever performance?

My first performance was in 1987, and it was by accident, actually. I was a professional heckler, so when events were going on, you know how you’ll have the noisemakers section where students would make noise during events; that was where I was. There was a striptease in school, a lady from the Congo. Don’t forget; at the time, makossa movie was in vogue. This lady came on stage to do the striptease, and it was the first time many of us saw a striptease. She came on, took off her clothes, and by the time she got to the underwear, students ran on stage. She got scared and ran off. So they turned to me and said, “Okay, we know you’ve been doing some heckling. Can you come and pacify everyone and make them sit still so that we can continue the show?” That was how I got on stage and managed to get the show back on. By the end of that semester, hardly would a show be held in school that I wasn’t a part of. So I started doing research into standup comedy, looking for jokes everywhere. I would look for jokes in Ikebe Super, in cartoons, Pa Johnson, Dauda, and then I stumbled on Readers Digest, and it became my go-to for jokes. So I would go to Readers Digest, get some jokes, localise the jokes, and start building on my sense of humour; it was raw, so I needed to develop it. By 1988 and ’89, I was touring campuses.

At the same time, you were studying law…

I was supposed to change to law. I was doing Religious Studies and Philosophy. All the time that I was touring campuses, I was making so much money, more than I was earning in monthly allowance from my dad, so there was no need to collect that anymore. My allowance was 100 Naira monthly, and I could make 200 to 300 Naira per event.

And if I do three to four events in a month, I could make seven times whatever my dad was giving me.

My dad eventually wanted me to get my transfer to law, but I was already comfortable doing comedy. And if you became a lawyer, you were not allowed to practise comedy, so I decided that there was no need to change to law. I stuck with standup comedy with a plan to do law after I finished my first degree, but the money (I was making) was too much.

This is why my autobiography is titled From Wigs to Wits.

You did comedy at a time when there weren’t clear examples to follow. How did you map out a career in standup comedy for yourself?

Occupational dynamics change. There was a time when everyone wanted to be a lawyer, accountant, doctor, engineer, or banker. Those were the five professions that were the signposts for many parents. When I told my dad I wanted to become a comedian, he had a good laugh and said, “Truly, you are really a comedian.” In hindsight, I understood where my parents were coming from because many parents at the time wanted to quickly set their children up in a way that when they retired, the children won’t become their responsibility. I didn’t see that at the time; I just saw it as they wanting me to be who they wanted me to be. Déjà vu, my son, many years later, came to tell me he wanted to become a DJ, and I was like, “DJ what? No, you can’t be a DJ; you have to finish your course.”

Comedy, over the years, has been at the forefront of social commentary, a powerful tool for addressing social issues. When you first started, at what point did it resonate with you that you could use your platform to speak to real-life issues?

Every University community is a small Nigeria in that you have a collection of everybody from different aspects, backgrounds, ethnic groups, languages, orientations, upbringings, educational statuses and religions, and everybody comes together in the university community. Within that space, I discovered the social-political boxes you need to tick. Remember that they organise elections too in school, there are also commercial activities, buying and trading of hostel accommodation; there’s religion as well with churches and mosques. By the way, Chris Oyakhilome started from my school; he was my next-door neighbour in school when he started Believers Love World. When I started standup comedy back then, chances were that because of how the small Nigerian communities in universities accepted it, it would be accepted outside as well. When we were in school, I would talk about the student union officers, bus drivers, girls and relationships, how guys are behaving, even nocturnal guys, how people run out of cash, the well-to-do children and ones that weren’t well-to-do. Comedy as a tool for social commentary hit me as a student, and I took it on.

Gradually you will notice that in many years to come, in most of my performances, I would reflect something about society, something relatable. So the relatability of the things said in my jokes is just to have them mirror society. There’s a formal saying that if you want to tell people the truth, you make them laugh; while they are laughing, you stick it down their throats. That’s what I did.

You’ve been around for 38 years, been a part of the industry since inception, and have seen comedians come and go. What do you think was the one thing you did that has kept your dominance of the industry to date?

I think it’s the fact that I still see myself as an underdog. The fact that I don’t think that I’ve arrived. When it’s time for the cheetah to run, he will still run. He won’t say because he’s the fastest animal, meat should be brought to him; he still goes hunting. I took that on. Standup comedy is dynamic; you are as funny as your last joke. If you want to remain relevant in society, you have to continuously hone your skills, exhibit your abilities and promote your creativity in any way that you can. So I became dynamic. Wherever the platforms are, where the conversations are had, or where people migrated to get their doses of information and laughter, I was there. When it was Facebook, I was there, MySpace, I was there.

When Instagram and Twitter came, I was there as well. You’d have to agree that standup comedy is not like being a lawyer or doctor that after a particular age, you’ll have to retire. As long as you can still tell a funny joke, you can still be a standup comedian. People tell me, “Oh, you’ve been in the game for so long.” I think you can be in the game for 10 years and make more impact than someone who’s been there for 35 years. But I must say that the time that it took us to grow and become recognised has reduced compared to today. If people consider the fact that times have moved on, we will then begin to see that the number of comedians you’re seeing now is growing because the hard work has been done.

Technology, new awareness and initiatives have also helped the growth to push the art. There are people who have become even more popular than I am because social media platforms and every other media that could help their career grow were there for them, something we didn’t have at the time.

How did the framework to make comedy professional begin?

The first step I took towards making comedy seen as a professional service was the fact that in 1993/94, I took billboards across Victoria Island. What did I write on the billboards? “Being funny is serious business,” and I put my pager number on it. Those billboards cost me 200,000 to 300,000 naira at the time. It was a lot of money, but in 1995, I made my first million as a standup comedian when I worked for Satzenbrau Guinness. They got me to tour the whole of Nigeria, and when that was done, my cheque came up to about 1.7 million naira, and my fees increased. Many changes at the time helped trigger the growth of standup comedy generally.

One such was that I had portrayed and pushed standup comedy as a service, not an art form. As a service meant that it was something that you needed to add value to whatever you were doing.

As an art form is something you just appreciate from a distance. For instance, if you know how to sing, you can sing in the church, in the bathroom or amongst your friends, it’s a hobby, and you’re just enjoying yourself.

But when you make it something that somebody wants to pay to watch, buy, download, and use as a soundtrack for a movie, it becomes a service. Until you make anything you have as a skill a service that somebody requires to complete a business process, it’s unprofessional. So I managed to push it through and get standup comedy to be accepted. There were a lot of sacrifices; I was going to events to perform for free. I would go to corporate events and tell them, “I understand you are having an annual dinner event. Can I have five minutes please?” And they would ask what I did, I’d tell them standup comedy, and I would perform for five minutes and leave. I was performing in boardrooms and on planes. When I started doing standup, we had people who were already in entertainment and started doing standup comedy. We had a name like Muhammed Danjuma, Alarm Blow, OAU, Omar Omar, Basorge Tariah Jr., Okey Bakassi. With time, we had the likes of Gandoki, who came and joined us, seeing that the business was booming. It caught on like wildfire because, after about a year of pushing the envelope, people saw that this business could be lucrative. But there were many naysayers who did not think that there was money in the business. We just needed people to first of all, understand the value proposition that standup comedy brought to their events and engagements.

So we went on radio and TV, and our popularity grew. The corporate side was the one that actually offered the biggest payouts.

Corporate billing brought a lot more money, and a lot more serious minds, and the people with deep pockets are in that space as well. For individuals, a lot of them weren’t still sure if they would pay. While they were still fighting to pay 10,000 naira, there was a corporate body that was already paying between 50,000 and 60,000 “When I told my dad I wanted to become a comedian, he had a good laugh and said, ‘Truly, you are really a comedian.’” naira. And many people did not know that we are making that kind of money.

The comedy industry has taken a different form. We talked about how comedy is a powerful tool for social commentary, and in today’s world, we have political correctness standing in the way of how stories are told.

Was it something you had to navigate through your career?

Political correctness is something that you cannot dance around. You either hit it head-on, it consumes you, or you float over it. What was happening most times is I learnt early enough to be discerning early enough to know how to walk the thin line between being funny and being offensive, and the golden rule is to not offend someone you’re going to be performing to. If you know that the performance is not a one-off and expect to perform there over and again, you need to walk that thin line then. Over the years, I’ve walked that line well. Having worked that line well, I now know how to navigate it. Audience reading is a very vital part of a comic’s performance. You can’t just climb on stage and grab the mic; you have to read the audience and gauge what constitutes them; are they lawyers, bankers, elitists, or a bunch of critics? All of that goes into your head as you’re providing the entertainment. So you are multitasking, as it were, knowing who and who not to tell jokes about, knowing what not to say to offend anybody, and just making sure that all you’re there for is laughter without being offensive. So as you do that over the years, many other younger comedians are watching and seeing how you do it and learning from you. The bottom line of all of these is that you still want to remain in business.

You also want to make sure that every time you perform, the performance you make at that show recommends you for another one. This is why I don’t do dirty jokes. Every dirty joke steals about 30 to 40 percent of your audience because there’s someone in that audience who will be like, “I don’t want this guy telling these jokes at my event.” I learnt not to speak vulgarly even though I am one of the people that know more dirty jokes than most, but you will not find me telling them.

How difficult is that?

It’s not difficult because most times the people who run into dirty jokes are people who don’t have original clean jokes to tell, so dirty jokes are low-hanging fruits. They are funny, but every time you tell them, the people who laugh at them are people who don’t mind being vulgar in public. It’s just like swear words; if they are so good, why don’t you use them in prayers?

Talking about the consumption of comedy today, more people now consume comedy from the comfort of their homes and that has shaped the new generation of comedians who now identify as skit makers, putting us in an age where we have more skit makers than standup comedians. Do you think it’s an easy way out?

It’s a difficult art form as well.

Making skits is like an e-monologue, like stage acting.

Acting on stage has its place in entertainment, just like acting on TV and radio. There are different ways that you can interpret an art form. Anybody that draws can paint anything, but a cartoonist adds humour to his paintings. A standup comedian is a funny person, but when you act it out, you are actor-comic. Many skit makers are actors with a great sense of humour. Some of them are standup comedians. It’s like when you find somebody who is an MC, and the person has a great sense of humour; he becomes a better MC. But you see, there are times that humour is not needed to be an MC, especially in a strictly formal corporate event. A skit maker is someone who uses his sense of humour to create something that you can watch on a device. It doesn’t stop you from being a comedian; it’s just a platform for executing the art form.

Don’t you believe they are running standup comedians out of the market?

Many of the guys that do standup are still doing their standup and have started doing skits. A lot of people who are doing skits have become so popular they are coming to do standups and even MCs as well.

So there’s a fluidity of creativity, and it is based on how well you can blend either as a skit maker or as an actor. Macaroni is an actor that started making skits; he chose a way to express himself better. The same thing goes for MC Lively, Mr Funny (Sabinus) and so on. It is a different platform and ways they use to push their sense of humour that differs, but it’s still the same.

You have to be dynamic; standup comedy is dynamic. When I came on the scene, some people were okay with slapstick. When I came on, I felt there was a way to do it differently, and I did mine differently. So skit makers are also doing it differently, and it doesn’t stop them from being comedians.

What would you say your comedy style is?

It’s fluid because today, I could do comedy of comparisons; tomorrow, I could do comedy of insults; another time, I could do tribal comedy. I could also do slapstick, depending on what I want to talk about. I could do mimicry and impressions, depending on who I want to talk about. The time and situation will determine what I apply.

Outside of comedy, we’ve seen you in a handful of movies, heard you on the radio, MC national events, and so on. What are some other things that you’ve been up to from comedy?

From comedy, I have gone into show promotion; I organise the January 1st concerts. I have gone into empowerment, scriptwriting, songwriting, writing copies for adverts, and writing scripts and speeches. I have also gone into ideas generation. Comedy has opened a lot of doors for me. I have a TV licence, Excusé Moi TV. I have also fulfilled a lot of things on my bucket list, and my bucket list is really long. I’ve written a book, helped to groom a lot of young standup comedians, toured, and done a standup performance for six hours. Standup comedy has opened a lot of doors for me. And like I tell people, if my career is to be weighed in percentages, I think I have done about 40 percent and still have another 60 to go.

How do you source materials? How do you find inspiration?

First, newspapers are a very lucrative source to get stories. People-watching and observations are also another way. Having conversations with like minds, and watching movies, our politicians are also good sources of materials. I source from personal experiences as well. I also believe that anytime you watch a movie, you should be able to make about three jokes out of it.

Are there some trends that you find exciting or concerning?

The fact that we are even on Netflix, I’m happy. You know the saying, ‘If you want to know more about a people, listen to their standup.’ There are some people who may not know anything about America, but when they watch some movies, it gives them an insight into what America is like. Same thing with standup comedy. The things that people laugh about speak volumes about them. I believe that comedy has a way of fulfilling several roles, and we just apply that.

You mentioned that you had achieved 40 percent and still have another 60 to go. Share with us what is left to accomplish.

We still need a purpose-built comedy club. Our guys are doing very well in this circumstance, but the cost of building a comedy club will not be equal to how much return on investment we will get. But we are getting there, which is why I believe that our presence on Netflix and Prime all point to the fact that there is a need for us to have spaces purposely built for comedy. You go overseas and see Laugh Factory and other comedy clubs; we need to have something like that in Nigeria. When I said there is a lot that still needs to be accomplished, there’s no reason why we shouldn’t have a comedy channel on TV that curates all comedy content and put it out. Many people are using YouTube to propagate their content, but why should there be a TV channel dedicated to news, music, music, sports, fashion and everything else but comedy? So there is a lot more work that we need to do. Beyond that, I started a spontaneity contest, the holy grail of standup comedy, and in the last seven years, I’ve given out eight cars. Once you can be on the fly as a spontaneous comedian, there is no end to your comedic abilities. I have a lot of things that I’m working on; I have two or three books that I have to write that will help anyone coming into the comedy space find their way around.

I also believe I need to do a lot more for female comedians. The number is dwindling; not many people are stepping into that space, so we want to see how we can trigger a search process so that we can encourage them to come and fill that vacuum.

Women are funny; the question is, do you accept their creativity?

A lot of people are concerned that women should not talk so freely. It is important for us to weigh those pros and cons, and the pros are that younger female comedians are needed in the space.

In conclusion, I would say that the reason many female comedians have not been up to it is that it’s a very brutal space. Standup comedy is one of the most difficult art forms in the sense that a musician can perform three to five songs, and two weeks later, somebody will be like, “I really did enjoy that band.” But with a standup comedian, it is instant, and somebody will be like, “he’s not funny.” A musician can repeat a particular song multiple times at the same event, and people will still enjoy it each time. As a comedian, however, you cannot repeat a joke at the same event. Even if you tell a joke you’ve told before at another event, some people who have heard it before will not be impressed. And this is why you hear comedians take offence at people who take their jokes and don’t give credit.

How have you dealt with that in the past, people who steal your jokes? Do you ever copyright your jokes?

No, but soon I will begin to, which is one of the reasons I did the six hours performance at the time. Many people were saying he’s not performing anymore; he’s not funny anymore. My argument is always that if I were a zero-ranked police officer on the Lagos-Ibadan expressway and I checked your particulars every time, and you then know me by my tribal marks, assuming I have some. If two or three years go by and I’m still on that road, it means I’ve not grown. But if you pass the road and don’t see me, ask about me, and they tell you I am no longer on the road and now a commissioner of police, that’s growth. It would be the same if I were a banker, upgraded from the entry-level position working in the bulk room, counting all the dirty, smelly notes, to the teller position in the banking hall, and then ultimately to an executive director in the headquarter. That’s how people grow. But people still expect you to remain where you were. Many people have told me, ‘Oh, I don’t see your performance anymore; you’re not a comedian anymore.’ And I’m like, “Where did you not see me?” Did Aliko or Femi (Dangote and Otedola) have a party and invite you? No. But they’ve invited me, and I’ve been to those spaces and performed there. Everybody thinks that you should still be on stage. John Momoh owns Channels TV, and he doesn’t read the news. You have people who grew up the ranks and got to a particular stage, and they begin to enjoy the hard work that they’ve put in. We are working on some really major things that will change the comedy space.

Self-identifies as a middle child between millennials and the gen Z, began writing as a 14 year-old. Born and raised in Lagos where he would go on to obtain a degree in the University of Lagos, he mainly draws inspiration from societal issues and the ills within. His "live and let live" mantra shapes his thought process as he writes about lifestyle from a place of empathy and emotional intelligence. When he is not writing, he is very invested in football and sociopolitical commentary on social media.