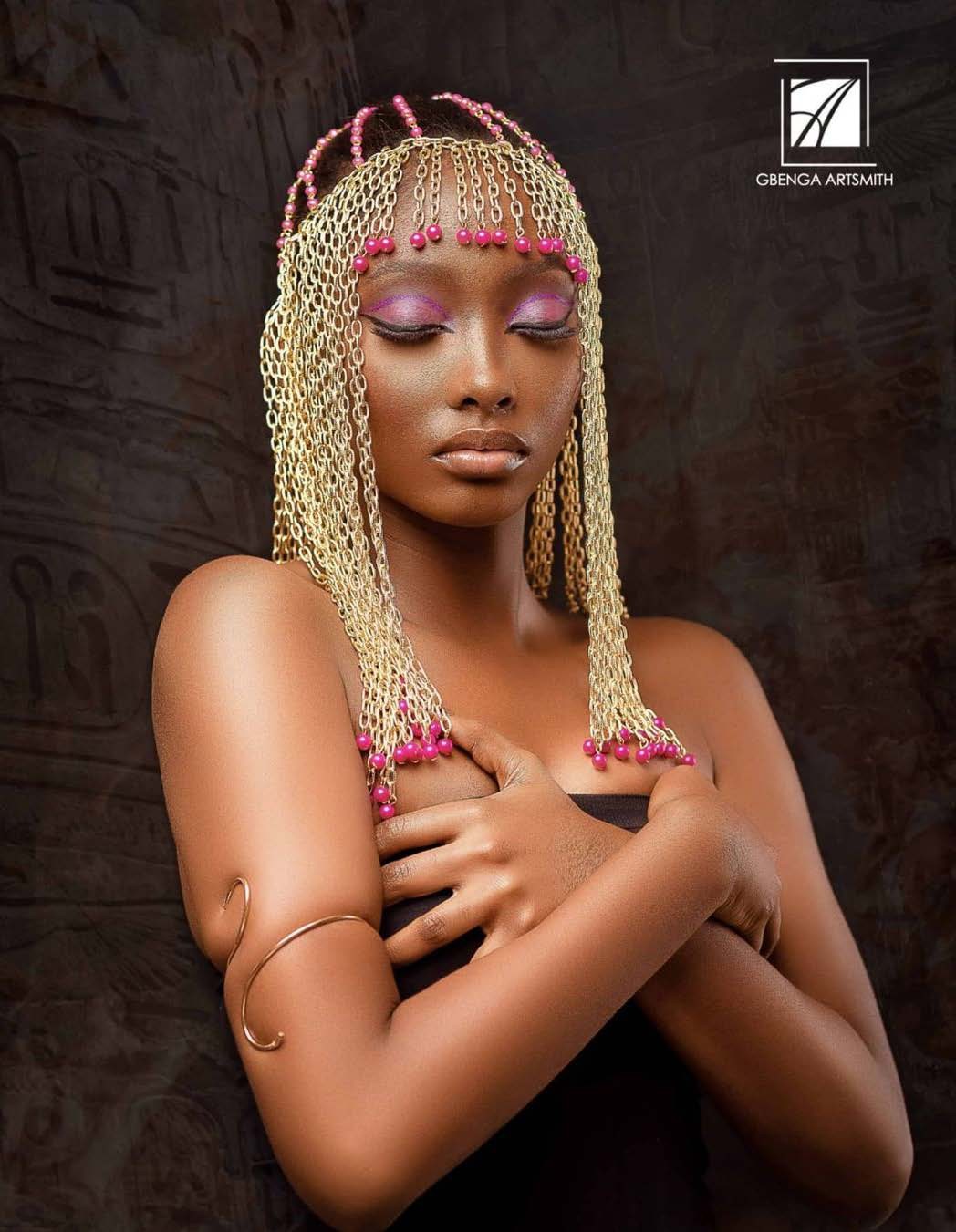

The Breast Cancer Conversation

From ages ago, man has had to combat several ailments. Think about a thousand years ago, before western medicine came to the fore, people found a way to stay alive. There’s no questioning how clever we humans are, so we turned to herbs to solve some of these infirmities at every turn—they kept our forefathers alive. Western medicine then came along and made living much easier. Well-researched scientists and medical practitioners over the years have not only found the reasons why our body malfunctions sometimes in the form of a diagnosis but also discovered different ways to rectify them. A particular ailment has managed to go unresolved, however—cancer.

Cancer Cells

Cancer is a disease in which some of the body’s cells grow uncontrollably and spread to other parts of the body. It can start almost anywhere in the human body, consisting of multiple cells. Typically, human cells grow and multiply

(through a process called cell division) to form new cells as the body needs them.

When cells grow old or become damaged, they die, and new cells take their place. Sometimes this orderly process breaks down, and abnormal or damaged cells grow and multiply when they shouldn’t. These cells may form tumours,

which are lumps of tissue.

Tumours can be cancerous or not cancerous (benign). Cancerous tumours spread into or invade nearby tissues and can travel to distant places in the body to form new tumours (a process called metastasis). Cancerous tumours may

also be called malignant tumours. Many cancers form solid tumours, but cancers of the blood, such as leukaemias, generally do not.

Benign tumours, on the other hand, do not spread into or invade nearby tissues. When removed, benign tumours usually don’t grow back, whereas cancerous tumours sometimes do. Benign tumours can sometimes be quite

large, however. Some can cause severe or life-threatening symptoms, such as benign tumours in the brain.

Cancerous tumours are much like the weed growing in our garden—plants that are not valued where they are growing and are usually of vigorous growth, especially ones that tend to overgrow or choke out more desirable plants.

Unlike normal cells, cancer cells have the ability to grow in the absence of signals telling them to grow, ignore

signals that usually tell cells to stop dividing or to die, hide from or trick the immune system—whose primary job is to eliminate damage or abnormal cells—into helping cancer cells stay alive and grow, and take energy from nutrients in a different way than most normal cells, aiding their rapid growth and movement.

On paper, cancer cells are very aggressive and, as a result, responsible for high fatality and the disenfranchisement of families who spend a fortune in money and time fighting this disease.

Breast Cancer

As the name implies, breast cancer is cancer that forms in the cells of the breasts. It has gained notoriety as one of the most diagnosed cancers, and although it can occur in both men and women, it is far more

common in women.

In Nigeria, where documentation was not the order of the day, breast cancer cases were historically low but are now increasing due to urbanisation and lifestyle changes. It is currently the leading cause of cancer deaths, representing about 23 per cent of all cancer cases, with approximately 18 per cent of deaths attributed to it in the country.

In the case of Nigerian women, breast cancer tends to be diagnosed at an advanced stage, and the chances of survival are low. Nigerian women are also more frequently diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer than women of European ancestry, with cases occurring at a much younger age.

As a result of the late presentation of the disease, the only options available are expensive treatment procedures, which may be unaffordable for the average Nigerian woman. Though there is a high incidence of breast cancer in Nigeria, studies have shown that the majority of Nigerian women, both in rural and urban areas, possess little or no knowledge about the risk factors and symptoms of the disease.

In cases where women are aware of these, there is hesitation in seeking healthcare, resulting in untimely death. Religious, economic and sociocultural factors have been shown to play a part in women’s attitudes towards the disease. There is also a lack of knowledge on breast self-examinations (BSE) and who should conduct them, especially in rural areas.

Clinical breast examinations and mammography have been recommended by the American Cancer Society

(ACS) for the early detection of breast cancer. However, there is a lack of organised breast cancer screening programmes in Nigeria, with only one state having a structured mammography screening program (Lagos State

Government Ministry of Health, 2010).

Visiting healthcare facilities to get screened is also low, which might result from cost restraints as many Nigerians

have to pay for healthcare out of pocket. Socio-cultural factors might also play a role in women’s readiness to

attend regular screenings in areas where it is available.

Not Just The Lumps

The thought of finding a lump in your breast is terrifying, but it’s important to be aware of your

breast health so you can alert your doctor to any changes. Beyond lumps, though, other changes could be signs of breast cancer. While lumps are the first thing many people think of when they think of breast cancer, breast cancer can actually present many other symptoms, too.

Here are the lesser-known signs of breast cancer that span beyond a lump in the breast.

• A lump in the armpit

• Nipple or skin changes

• Nipple discharge

• Something that appears to be a breast infection

• A change in breast size

• Other physical changes can also be signs.

If a well-structured mammography screening program is non-existent, these symptoms will easily slip through the cracks and go unchecked. This is the fate of most Nigerians.

A Glimmer of Hope

A small clinical trial discovered that every rectal cancer patient who got an experimental treatment saw their disease

vanish in what looks to be a miracle and a “first in history.” According to the New York Times, 18 patients took a medicine named Dostarlimab for six months in a limited clinical trial done by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and all of them saw their tumours shrink at the end.

Experts stated that the malignancy is undetectable by physical examination, endoscopy, positron emission tomography, PET scans, or MRI scans. This shows that Dostarlimab has the potential to be a ‘possible’ cancer cure for one of the most lethal tumours.

This is “the first time this has happened in the history of cancer,” according to Dr. Luis A. Diaz J. of Memorial Sloan

Kettering Cancer Center in New York. Dostarlimab is a medicine made in a lab that functions as a surrogate for antibodies in the human body, according to specialists.

Individuals in the clinical experiment previously received treatments such as chemotherapy, radiation, and invasive surgery, all of which could cause bowel, urinary, and sexual dysfunction. The 18 patients expected to have to go through these surgeries as the next step in the research.

However, they were surprised to learn that no more therapy was required. Experts were astounded by the trial’s outcomes, stating that total remission in every single patient is “unheard-of.” Experts praised the study because not all participants experienced serious side effects from the medication trial.

Dr Alan P. Venook, a colorectal cancer specialist at the University of California, said that complete remission

in every single patient is “unheard-of.” He hailed the research as “world-first.” “At the time of this report, no patients had received chemoradiotherapy or undergone surgery, and no cases of progression or recurrence had been reported during follow-up,” researchers wrote in the study published in the media outlet. Cancer researchers who studied the medicine confirm that it appears promising, but a larger scale trial is required.

In Finality

At every point in history, we have been plagued with several diseases. Whenever these pestilences come

knocking at our door, a cure has been discovered to mitigate their risk. We don’t have to look too far for case studies. In 2020, after the COVID-19 virus brought the entire world to a halt in a global pandemic, it didn’t take too long for scientists to come forth with a cure in the form of vaccines.

Of course, a vaccine was concocted—the world economy was affected. Think about the fortune that American

pharmaceuticals make from chemotherapy and every other form of cancer treatment. Playing the devil’s advocate, it is not so far-fetched to tie the lack of a concrete solution to cancer to economic greed.

Cancer continues to be one of the most common causes of death worldwide. A total of 1.9 million new cancer cases and 609,360 deaths from cancer were projected to occur in the United States at the beginning of the year, which is about 1,670 deaths a day.

With such ridiculous numbers, one would expect it to be treated as an epidemic. Every year, we have the cancer conversation, give prominence to the colour pink, and spread awareness as much as possible, but at what point do

we start discussing a permanent and mainstream cure? When will the apocalyptic nature of cancer become a thing of the past?

As Nigerians, we are not privy to these answers, even though we are sitting ducks for this deadly force that has directly affected us and our society. Hopefully, a cure will become mainstream in the nearest future, but until then,

watch out for the lumps.

Self-identifies as a middle child between millennials and the gen Z, began writing as a 14 year-old. Born and raised in Lagos where he would go on to obtain a degree in the University of Lagos, he mainly draws inspiration from societal issues and the ills within. His "live and let live" mantra shapes his thought process as he writes about lifestyle from a place of empathy and emotional intelligence. When he is not writing, he is very invested in football and sociopolitical commentary on social media.