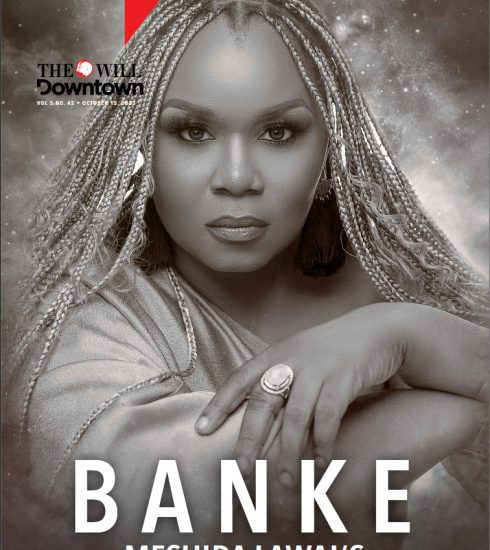

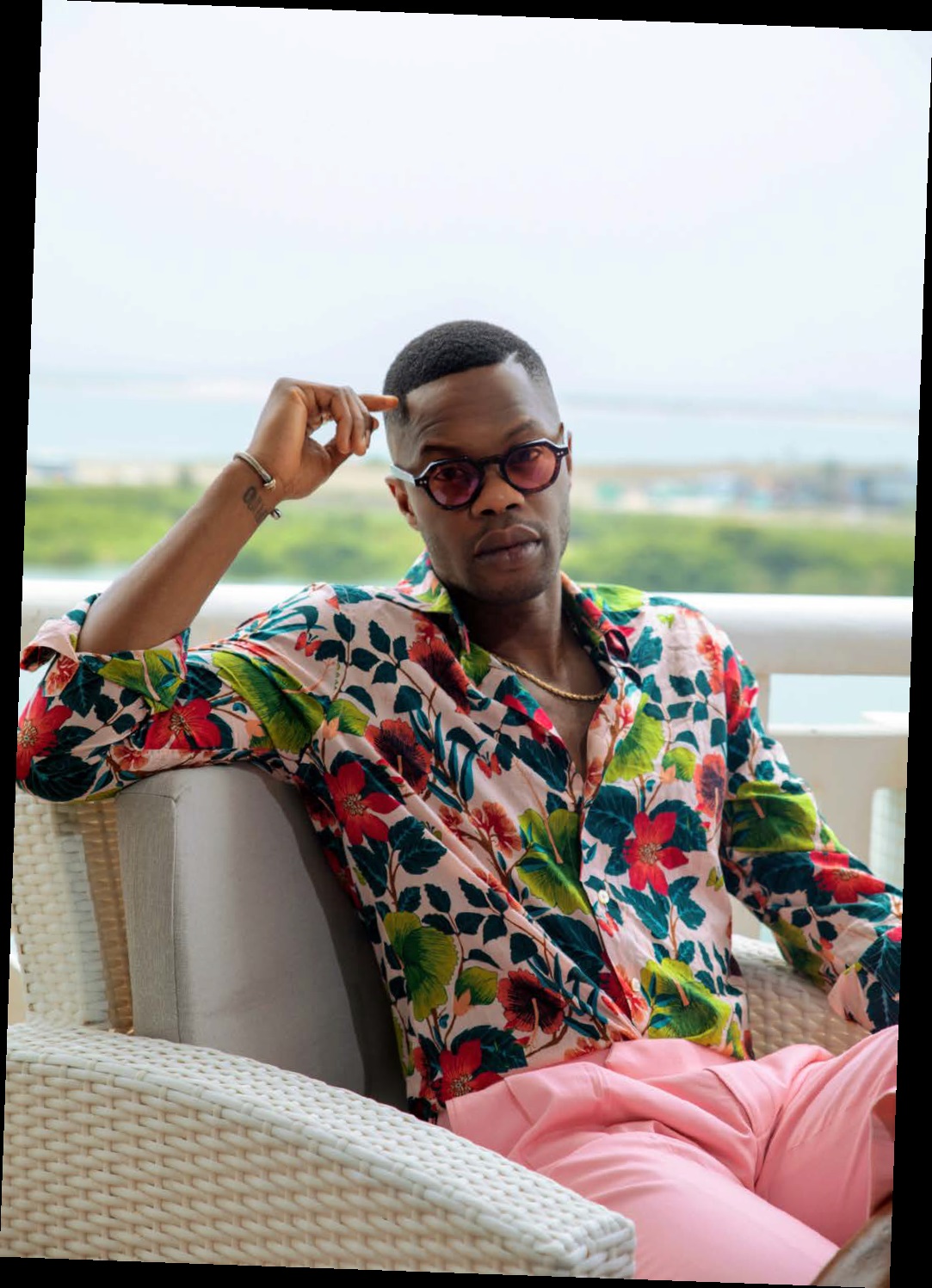

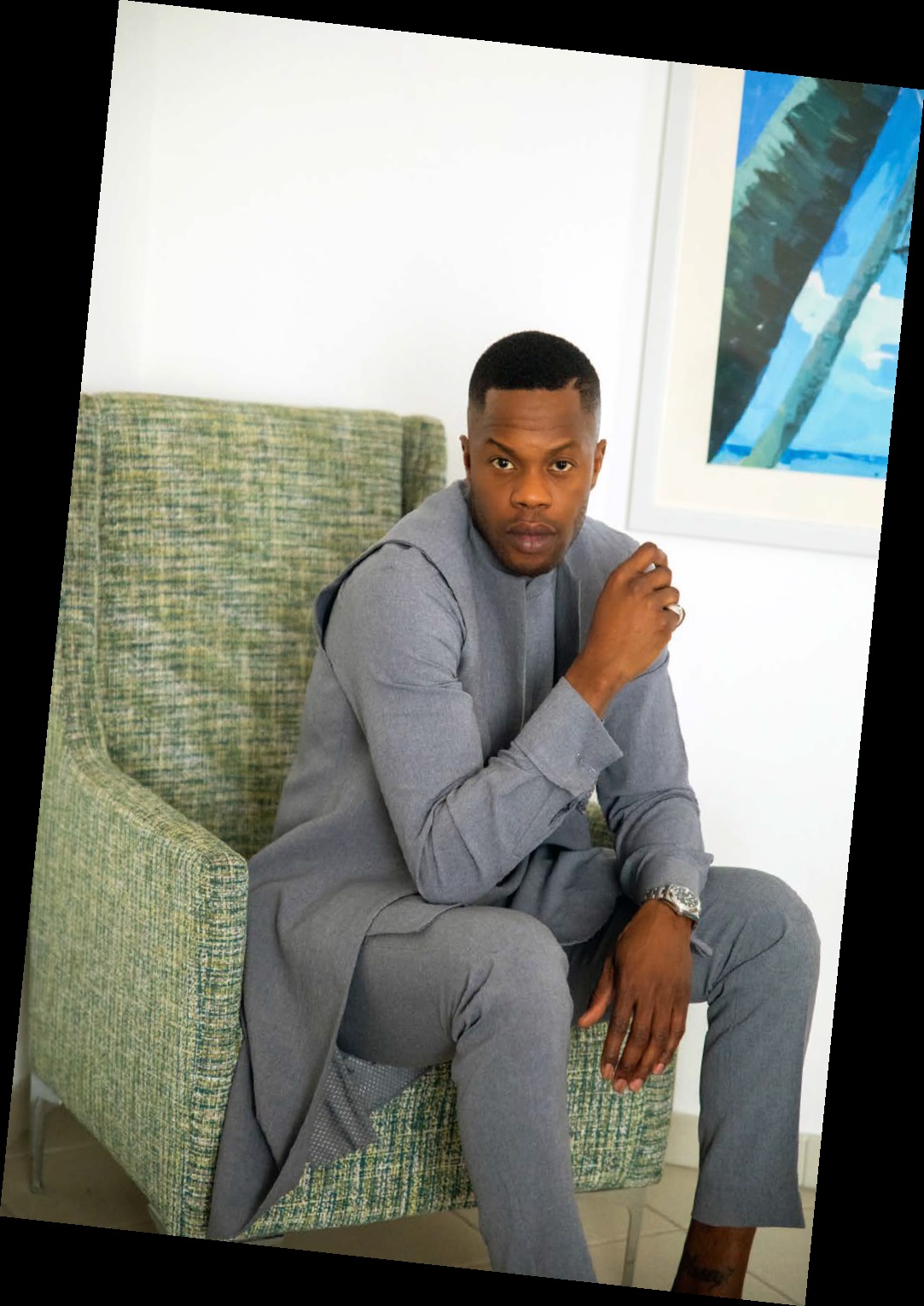

Bringing Hollywood Home: Sam Adegoke

“Awon omo Blake ti wan ti sonu, ika owo mi bayii lowa,” (which translates to ‘I have Blake’s little lost children in the palm of my hand’) a fictional character, Jeff Colby, acted by Nigerian actor, Sam Adegoke, tells his dad, played by fellow Nigerian actor, Hakeem Kae-Kazim, in a scene of America’s hit TV series, Dynasty. When this particular episode aired, it was the most discussed thing on Twitter—an actual Yoruba man was speaking the original Yoruba language on American TV. Nigerians were visibly thrilled by the representation.

Arts have always been the vehicle that fosters cultural intertwining. We have recently seen that vehicle oiled up to allow a more significant cultural shift that has since placed a positive spotlight on Nigeria and its people. But before afrobeats began its push for mainstream acceptance and the partnerships that help export our talents abroad were formed, one man didn’t hesitate to represent Nigeria on the biggest stage, Sam Adegoke. When Sam, who was already cast to be in the series, Dynasty, pitched to the showrunner, Sally Patrick, to make his character and his family hail from the most populous black nation in the world, it was a novel idea that would end up thrusting him into the limelight, quickly turning him into fans favourite, not only in the United States where the show was made but also back home in Nigeria.

DOWNTOWN’s Editor, Onah Nwachukwu, chats with the actor about his upbringing, which was split between both countries affording him dual citizenship, navigating America as a young black man from a strict missionary household that had TV banned, and eventually ending up in Hollywood as one of the country’s biggest exports on TV.

What was it like living in America as a Nigerian child? Were there any rules and guidelines that your parents instilled in you that were Nigerian culture?

Yes, absolutely. Excellence in everything. There was no room for anything else. My parents come from rural Ibadan, and my father’s family were farmers. And then, he got a very junior-level position working for the US Embassy in Nigeria. And that’s how we were able to get dual citizenship. So coming from that type of rural background, you can imagine we get to America, the Promised Land, and it’s the same story that any immigrant Nigerian or African family deals with. It is academics, and if you’re not in school studying, you’re at home studying. If you’re not at home studying, you’re praying in church. And if you’re not in church praying, you’re working. So those are the four things you could do. Back then, it felt very rigid and regimented to me; very shackling, and I hated it. There was a certain level of freedom that I did not feel growing up in that environment, coupled with the fact that my parents were ministers in this church— Deeper Life, and launched a church in St. Paul, Minnesota, where I grew up. When you’re young, you don’t see the value of that. As you age, those things stay with you. I’m grateful for the incredible opportunity to do what I love to make a living. And I recognise that’s not afforded to all, so that same discipline instilled in me with academics and relationship with God, etcetera, is the same thing that I apply to my work. Because I know it’s rare to have this, I want to make the most of it.

How did you decide you would be an actor for a child brought up by parents who are ministers at Deeper Life church?

They don’t watch television(TV). It’s so funny you said ‘no TV’ because my brother James bought this small black and white box TV, and we would hide it in the closet and bring it out sometimes to watch shows like Martin, Fresh Prince, you know, all those shows that were like popping in the 90s. The funny thing is—life is so interesting—the same people, my parents, who weren’t encouraging of the arts (because they want you to become, as they say, a doctor, lawyer, engineer or a disappointment, right? Those were my options), are the same reason I went into acting. My mom is an amazing storyteller, she was the first person who ever told me stories, and she tells these strange Nigerian proverbs, you know, ‘if you kill a goat, you will die,’ you know those kinds of stories, and I’m sitting like, ‘what the hell does this mean? Can I just go back outside and play now?’ So I always grew up with this love of storytelling, and we’re just natural storytellers by virtue of our culture. And then, in our church, we did faith-based plays, David and Goliath, The Resurrection, The Birth, The Death. My brother would often write the plays— I’m the youngest of seven, so we all have to have something we do in the church. My sister would also co-write with him. And then they would direct the plays, we were all like 8, 9, 10, dressed up in your long white kaftan holding your staff, and playing Moses or something, and I just enjoyed it. I think that, and my mother’s storytelling was what sowed the seed of ‘this could be something that you could potentially do for a living.’ But I didn’t do it till much, much later, just because of fear. So you pursue what you think you need to pursue based on that idea of, you’re here, in this country, so you have to make the most of it. There’s no time for anything frivolous, no time for the arts; you have to earn income and support your family, which I did for many years. I didn’t get around to pursuing acting until many years later. I’m grateful that I did that. That moment finally happened, and I was like, ‘listen, ayeopemeji, (life doesn’t come around twice). So you can have a good income, I made good money working in corporate, you can travel and do all these things, but if it’s not fulfilling, then you’re just earning a living; you’re not actually living.

What was your parents’ reaction to you deciding that you wanted to act for a living?

They almost crucified me. I studied Marketing and Finance at Business School. I worked in consumer insights and human resources, and the company I worked with—General Mills, moved me to LA (Los Angeles). The crazy thing is I have a very artistic family. I have two brothers who can sit here and draw you; it will blow your mind. My sister sings and plays the piano in the church. I played the bass guitar in the church, and my brother Michael drummed. I always tell people we are like an African Jackson Five, but we did praise and worship in the church. Funnily enough, I enrolled in a theatre arts program during my freshman year, but my eldest brother said, ‘No, not in this house. Don’t study that. Study business or marketing. That’s what’s acceptable in this house.’ And I worship my older brothers because they raised me when my parents were busy working in the church. I did. I did it for many years. And then, I finally just said, ‘No, this, this isn’t really me.’ So I cashed up my 401k, quit and went to the Academy of Art in San Francisco. They have an art program there. And I didn’t even tell anyone. I studied menswear in theatre because my uncle was a tailor in Nigeria, and I always liked to play around with clothes. People knew I was doing that but didn’t know I was doing the theatre because it’s still like, you’re going to move to LA and become an actor; it just sounded cliche, sounded stupid. And I’m grateful I didn’t tell anyone because they say, ‘A prophet is not without honour save in his own country’, right? It’s usually those closest to you because they already know you in one light, and there’ll be the biggest voices of dissent towards your dreams, and they do it unknowingly. I would do the same if my brother showed up tomorrow and said he wants to be like a jazz musician. I would laugh like okay, you’re an engineer; that’s how your mind works. I wouldn’t say it out, but I would think it in my head. So I just kept doing it.

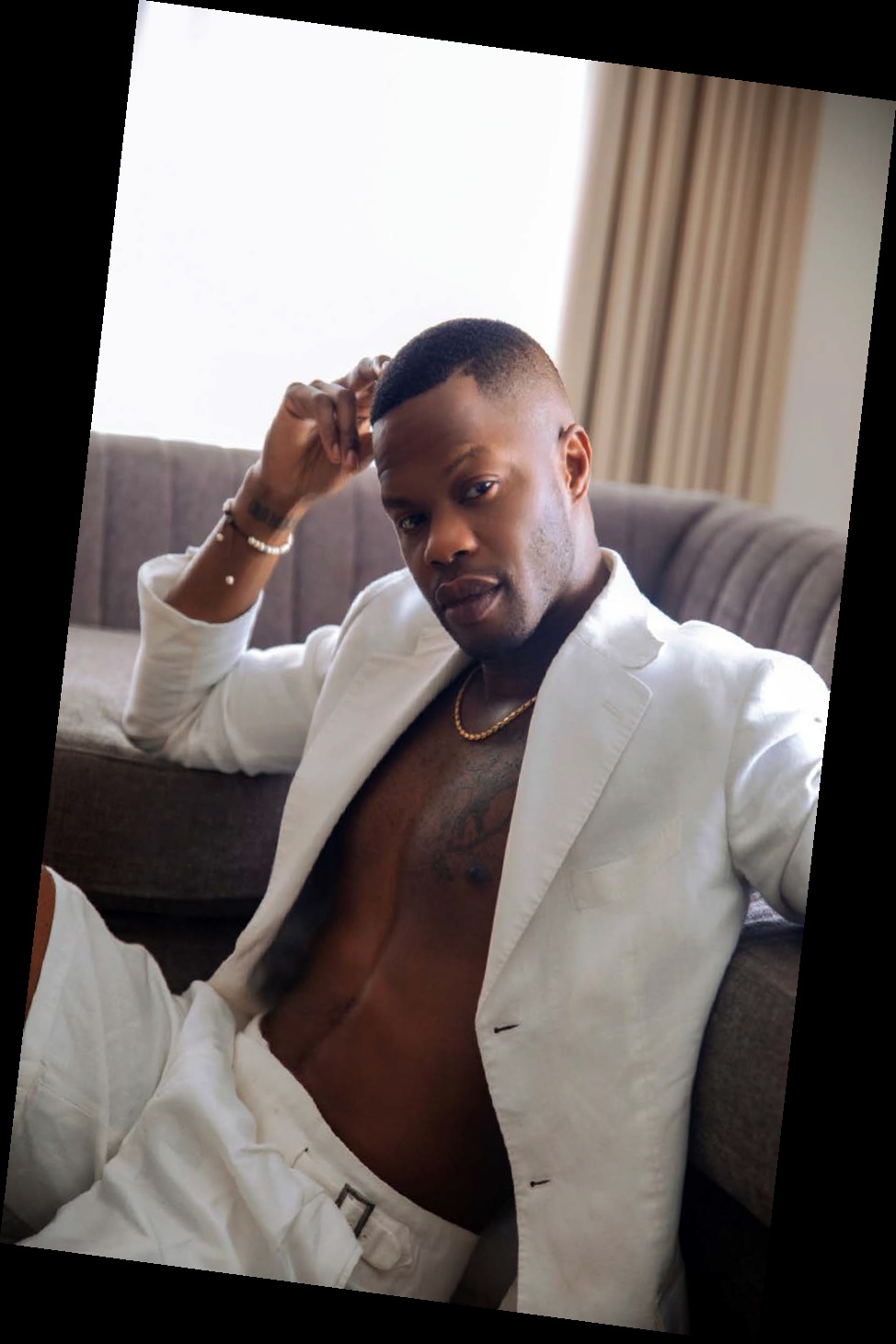

What do you love about acting?

Contrary to my character on Dynasty and that show’s tone, acting is therapy for me. I mean, I jazz it up and make it sound sexy, but I remember, funny enough, my older brother, John, was the first one to start taking acting classes in LA. I was doing some runway stuff, dabbling around entertainment, and he invited me to the class he was taking in LA, in a studio theatre— Ivana Chubbuck’s class, to sit in on it. He’s like, ‘listen. I think there’s something here. I think you could do this. I’ve been doing this class for about four or five months.’ So I sat in on the class and watched my brother perform a scene with another scene partner. And I was like, ‘Who the hell?’ I didn’t know who this guy was. It was a deeply emotional scene, coming from a guy who was a part of a family of six very macho boys, so you can imagine my surprise. I had never seen this emotional side of my brother, and afterwards, I was like, ‘John, what the hell was that?’ And he didn’t have the language to articulate his experience. So I jumped into it and realised, ‘Oh, wow, this is therapy.’ There are some things we need to deal with— being Nigerian men, particularly, that we can embody within a character through which you kind of exercise these things. It’s not Sam crying and being moist; it’s the character. But you don’t realise you’re releasing stuff through that. And that became like a drug for me. I was like, ‘Okay, I’m learning more about myself outside of the professional side of Sam, the athlete outside of Sam, the man or whatever idea man is supposed to be. You’re discovering that for yourself. And that’s what I love most about it. It’s become therapy for me. It led me to do therapy myself with a formal therapist, which was a hilarious concept to me growing up. when I was younger, I thought, ‘why are you gonna pay a complete stranger to tell you about yourself?’ Like, ‘give me your money, and I’ll tell you everything about yourself.’ Now, I tell my brothers, ‘all you negroes need therapy. You guys need some things you got to work through.’ So it’s just beautiful, it’s being a child again, it’s make-believing, pretending and to do that for a living? God is good.

Have your parents come to terms with it?

I still don’t know if my parents know what the hell I do (laughingly)— just kidding. I mean, they do. Now it’s like, ‘My son; he’s on Dynasty doing his thing. Have you seen him? God is good.’ But my parents are so spiritual, there were certain times I made the mistake of watching an episode with my mom, and I didn’t want her to see it. It was an episode where Jeff and Fallon finally fornicate. It’s a really heavy scene, and my mum says, ‘See my son, see my son on TV, just baring your chest like a male prostitute for everyone to see. Is this what you’re doing? Is this how I raised you?’ And then the episode ended, and she was like, ‘Okay, so when is the next one?’ I had her hooked, and then she watched the whole series and had so many questions. So they finally came around, but it was undoubtedly a long journey, and it continues to be. But my mom knows I’m writing now because I want to write and develop stories out of Nigeria on a global scale. Great stories like the story of Ken Saro-Wiwa and the Delta people, the Ogoni people, and Dele Giwa— our heroes. They’ve made the Martin Luther Kings and Malcolm Xs in America, so I want to bring these stories to a global front. And she consistently asked about that. So she supports me now.

What was your very first role as a paid actor?

My first role was in a show called Wicked City on ABC.

Was it difficult getting the role considering that you are a black person in the US, or with the inclusiveness nowadays, was it that they were looking for a black character for that particular role?

They were. However, this was before what I call ‘the black renaissance’ in entertainment started happening, with Black Panther, Moonlight, and some of these amazing stories that pushed things forward. At the time, the roles available primarily to you were either gangster or slave, which was my first role. I played a drug dealer. But the way the role came about was ABC, speaking of being more inclusive, has a digital talent competition that they do. Every year, they take submissions from all across the US. 20,000 to 30,000 people submit. You do a series of dramatic and comedic scenes, selftaped, put it in, and they’ll let you know if you made it onto the next round. The idea of it is that they wanted to get more diverse casting in their programming. So I started doing it. The contest is called ‘ABC Discovers Digital Contests’, which happens annually. 2015 was, I think, the second or third year, but Lupita Nyong’o did it. Several people I know, prominent actors and black actors, went through this program. I did it just as another way to work because, at the end of it, you could win a holding deal with ABC, and they’d give you 20 thousand dollars and have you meet with all their producers and showrunners and try to get you staffed on a show. I was like this is another opportunity to excel, and I kept going through the rounds. Then they told me I was a winner out of thousands of people. And before that, I was doing student plays, student projects, extra work, and whatever I could do to be there. And that’s kind of how the career took off. So through the program, I got the exposure that allowed a prominent agency and a management company to reach out and say, ‘Hey, we love your work. Congratulations on winning. Do you have representation?’ I signed with them; they sent me to my first audition, ABC’s Wicked City, and I booked that. They didn’t sign me immediately. It is a pretty major management company, so they’d rather try you out first. I kept working, and thankfully, I’ve just been working ever since, and I’ve been fortunate to do a pretty diverse array of roles that keeps it fun and exciting.

Let’s talk about the exciting one—Dynasty. How did that come about, and why were you drawn to the role?

I auditioned for it in 2017, and what drew me to the role to want to audition for it was the fact that it was a black billionaire. I’ve never seen that on television. Once again, the roles available to me were in 2015 and 2017, and I was like, ‘Yes, this is something I could get behind. An intelligent guy, he’s well-dressed and likes to cause trouble.’ So there are some similarities between us. But I just liked what that character stood for, and I went through about five or six rounds of auditioning for it, booked the role, and then we moved to Atlanta and filmed for the last five years there. We just wrapped, so yeah.

So that’s bye-bye, Dynasty?

Done. Done. Done.

Are you hoping to do something else in that light—series, or are you looking to go on to the big screen?

I want to do more films. I just did a movie, but it’s on HBO max right now called This is Not a War Story. It’s about a community of real-life veterans in upstate New York that creates art on their uniforms. They make paper out of their uniforms. So they spent three generations of warfare, World War II, the war in Vietnam and the war in Iraq. And that is a deep exploration of trauma. I want to tell stories that matter. I want to take characters I’ve learned something from that I feel can teach people who look and have had my experience. I think trauma is something we certainly don’t explore as much in black communities, in African communities, and certainly not as black men. So to portray this guy on this journey that he goes on, of mentoring a young veteran from the war in Iraq, who commits suicide, bringing up all his demons from his service, and him struggling with his suicide, and then finally, finding this community and a reason to go on? It’s a really beautiful story that I’m really proud of. I got to produce on it; it was my first time producing. We were nominated for a Spirit Award, which was really great. I was nominated for Best Actor at the indie film awards. So those types of stories. To me, the medium doesn’t matter. It doesn’t have to be filmed, and it doesn’t have to be on TV. It just has to be a good story. But yeah, I want to do more films. More series? Dynasty was fun, but we did 22 episodes per year. It’s a lot. And it’s tough to do other projects. I’m grateful to be working, but I’d rather do something that’s 10 to 13 episodes if it’s a series, so you can go to movies in between, keep it fresh, and keep getting challenged.

Apart from your character in Dynasty being a billionaire, what would you say stood out and was inspiring for young African men?

Yeah, I mean potentially. I get a lot of messages, DMs and tweets, particularly from Africans and Nigerians. Young guys are like, ‘Jeff Colby, so he’s Naija. To feel like you inspired something is what I’m most proud of in my career. I think it’s the visual of him, his style, how he carries himself, the fact that he’s self-made, that he came from nothing, all that resonates with me. We didn’t come from much, an African messenger in America, we grew up poor, I was on free lunch, and we were getting some subsidies. And here we are with a successful, hard-working family. So that was part of your story. I don’t know if it’s like, ‘oh, this is why I want to be Jeff,’ but the message I get is that people took note. For me, at least Nigerians felt seen on a major network television show, and that’s just what I want to do, to make us feel seen, particularly in the Western world, because Africa is the continent that’s consistently cast aside.

When it comes to acting, Nigerians are now killing it. What do you think is the reason for the increase of Nigerians being more visible and thriving in the entertainment industry abroad?

I don’t know that I speak for all, but I can speak for myself. I think it’s just us. It’s how we carry ourselves. When a Naija person enters the room, heads will turn. It’s not like an arrogant thing; I think we have a sense of self-belief. It’s not to say we have it more than anyone else, and that’s why we’re successful, but I think it’s our work ethic. I think the fact that we’re willing to explore and dig deep, as Nigerians, we have to make it happen one way or another. But I also think that the industry is being more open to us.

How can people get spotted?

Two things need to happen. You can be great and work hard, but even with the opportunities, they might need to see a character that you fit. However, if you’re bringing something really interesting, they will be like, ‘why don’t you show us some more?’ But yeah, we’re artists, storytellers, and musicians. You see what’s happening with our music? It’s so inspiring to me. And I want to keep pushing the needle and make sure that it’s not just a trend but also that we have a seat at the table. And then we can drive these things so that people who have had our experiences or are from us are also pushing us forward if that makes sense.

Speaking of a seat at the table, Hollywood seems to be scouting Nigeria these days, so there’s that intersection between Hollywood and Nollywood. In terms of business and exposure for Nigerians, do you think it is an advantage for us or is it a case of exploiting, as is quite familiar with these situations? Yes, we are breaking into Hollywood, but is there some segregation at the end of the day?

I think it’s a very complex question that you’re asking. Where I would like for us to be is to recognise how we don’t need anyone. Hollywood is the gold standard, it’s what everyone subscribes to, and it’s an industry of excellence. That’s where it started. For me, it’s twofold. I love that the Western world is making this investment, but also, I would like us to create a consortium of ourselves and support ourselves. Look how many stories are coming out of Nigeria; we could create our own industry here, but we have to level up the excellence and by the way, that comes from leadership as well. I hear you that it could be exploitation, and I have seen and feel like that’s happening. That’s why I want us to be in leadership positions. But if our leadership is making it difficult to produce premium quality content here— you call your production company and have to grease all these elbows. The entire budget is finished before you’ve even said, ‘action.’ It makes it difficult. So I understand people saying, ‘screw that, I’m going to go here to the Western world where there are more resources. Somebody cares, they’re going to give me a budget, and I can actually do something with it.’ So I still think everything starts with leadership, which is why I don’t know when this will publish, but come February 25th, make sure you get your PVCs and vote. But yeah, it stems from us. We have to get better, do better and realise what we have. And then we don’t need to chase certain standards, but we can create something within ourselves. But a partnership is also great. If we can partner with that world and learn from each other, that’s how everything progresses. So I don’t think they are mutually exclusive. I think both can happen. I would like for us to be more independent and self-contained, work with each other more, and trust each other more. But I also like the idea of partnering; that’s a gold standard. All we can do is learn.

Speaking of improving ourselves, you mentioned earlier that one of the things you’d like to do is open a film school. Why are you interested in doing that? Tell us about that.

Yeah, an acting and a film school, like a full-blown everything with opportunities for people to learn every aspect, directing, producing, line producing in front of the camera, behind the camera, gaffing everything. We are doing it; it just feels fragmented. It’s a goal, a dream. I have to bring something back here that can be a longstanding institution that students here who want to go into film don’t have to rack up all the money, try and get a student visa and go to USC or New York Film Academy in the States. We can go to the film school here and hopefully get the leadership, partnerships and government that will allow us to matriculate into jobs and opportunities here. Something for the youth. We have to keep the resources here. I think of the opportunities here; you look at people like the Ikorodu Bois, turning water into wine. The insane creativity here is just something that always inspires me. I think we lose sight of that sometimes with all the hardship and challenges in Nigeria. I think people are losing hope and inspiration, but I also think sometimes it takes somebody outside to remind you, ‘No, this is amazing to me.’ I was walking around Surulere, in the marketplace, or Ibadan, and I saw people with craftsmanship and innovation. They make sandals right in front of you. That, to me, is amazing. Who knows what we could do if you add a little bit to give people opportunities? So, film school is something that I believe and hope I’ll be able to do before my time passes.

Do you come home quite often?

At least once a year. I want to start coming more. It’s hard to film Dynasty, particularly during COVID. We weren’t supposed to travel. But I want to come, learn more, meet with more people and figure out where the bodies are buried so you can figure out what partnerships you want to make, genuine partnerships. I have to keep coming back more. So now that Dynasty is done, I have more time until the next thing.

I know that you do some charity work. Are you working on something else at the moment as well?

Yeah, I try to do something. A couple of friends and I did a ‘Feed Agege Railroad’ two Christmases ago, so we did it again last year. And then there’s an organisation called the Stand To End Rape (STER), which I supported in 2018 with this amazing young girl, Ayodeji, who has created a haven for women victims of sexual assault. I knew that happened, but then you sit to hear stories, and it hits you. I don’t have a set project; it’s just one I might hear about and want to partner with to try and use whatever platform I have to support and amplify in some way. There’s not always a reason to reinvent the wheel; there are so many organisations doing something you can supplement. But I absolutely will when something makes sense for me to do on my own. My focus right now is the film school. Whatever happens before that, as long as it’s happening in some way, it’s all that matters.

Having travelled around Nigeria a lot, what do we need to work on?

Not to sound all kumbaya, but we must work on love. I don’t know how else to say it. There is so much abundance in this country, and it, pardon my language, blows my f__king mind how we can have a leadership that can turn a blind eye to people suffering, take their own constituents and literally not care about anything else whatsoever. And it’s like, ‘how much is too much?’ But there is so much abundance. That’s really what it is. We are divided, but that was largely by imperialism. As far as I know, I don’t think people talk about this; we have to be the most ethnically dense country on earth. Nigeria is roughly the size of Texas, with 210 million people. No one knows how many tribes, the numbers range from 200 to 350 distinct tribes, dialects and languages, and how we are grouped in a country that’s less than 100 years old. Of course, there are going to be a ton of problems. However, at some point, you have to put all that aside—the tribal and religious lines that divide us and just love. Think about helping your fellow man. That’s the stem of all the problems, and I think even the Western world is becoming more divided and dichotomous with this normal discourse. So it’s not like I can talk to you, and we can agree to disagree. It’s more like you’re not with me; you are against me. I think it stems from leadership.

I hear you are a good cook. What’s your favourite Nigerian meal?

My ewa (beans) is a mad ting. It’s too many. I like pounded plantain. I also make good egusi. Sometimes I go to my mum’s and I take lessons.

Is Sam Adegoke taken?

No, I’m single and searching.

What’s your type? Does she have to be Yoruba?

No, I’m not going to comment on that because love conquers all. For me, love God: want to further yourself in some way, don’t take yourself too seriously and be adventurous.

What’s your favourite Nigerian attire?

I like fusion right now. I like traditional attire, sokoto, and buba; I like that it is fused with different fabrics. I like the idea of uniforms, something simple. I mostly wear black instead of colourful suits, just something interesting.

Intro by Kehindé Fagbule

A lawyer by training, Onah packs over a decade of experience in both editorial and managerial capacities.

Nwachukwu began her career at THISDAY Style before her appointment as Editor of HELLO! NIGERIA, the sole African franchise of the international magazine, HELLO!

Thereafter, she served as Group Editor-in-Chief at TrueTales Publications, publishers of Complete Fashion, HINTS, HELLO! NIGERIA and Beauty Box.

Onah has interviewed among others, Forbes’ richest black woman in the world, Folorunso Alakija, seven-time grand slam tennis champion, Roger Federer, singer Miley Cyrus, Ex Governor of Akwa Ibom State, Godswill Akpabio while coordinating interviews with Nigerian football legend, Jayjay Okocha, and many more.

In the past, she organised a few publicity projects for the Italian Consulate, Lagos, Nigeria under one time Consul General, Stefano De Leo. Some other brands under her portfolio during her time as a Publicity Consultant include international brands in Nigeria such as Grey Goose, Martini, Escudo Rojo, Chivas, Martell Absolut Elix, and Absolut Vodka.

Onah currently works as the Editor of TheWill DOWNTOWN.