Say Hello To The First Female Attorney General Of Lagos State: Hairat Aderinsola Balogun, OON

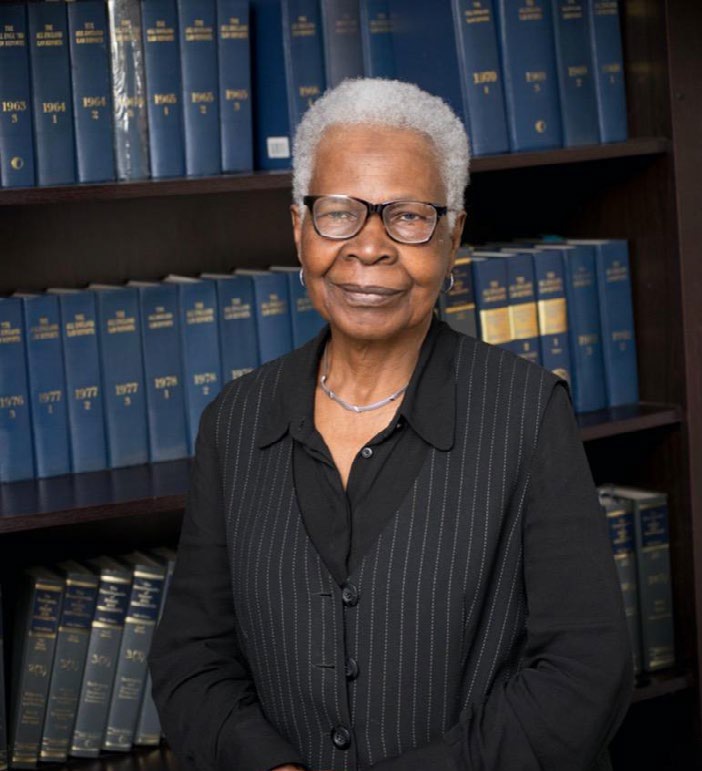

A first glance of Aderinsola Balogun, OON, you would see a smartly dressed woman still in good form, wearing the signature colour of lawyers—black and white. At this meeting, she is wearing a trouser suit. It doesn’t occur to you that she is an 81-year-old lady, especially as she still comes to work at 8.00 am. And just like her days serving as the Attorney General when she arrived before the Governor, today, she gets to the office first, even before her much younger business partners.

Hairat Aderinsola Balogun, OON did and still does an exceptional job as a legal practitioner today. Balogun’s legal career is unrivalled on the pulpit of equity, where women dare to challenge the status quo and show their mental capacity to thrive exceedingly in traditionally male-dominated fields.

“A woman of many firsts!” is the befitting appellation to describe Hairat Aderinsola Balogun, OON, first female Attorney-General of Lagos State, first female General Secretary, Nigerian Bar Association (NBA), first female Life Bencher( Chairlady, Body of Benchers), and first female President and member of Rotary Club Lagos. She was also the second woman Attorney General in Nigeria during the military regime of Governor Gbolahan Mudasiru. She is also a Life Bencher.

As she bids someone who may have been a guest or client goodbye, her son, Afolabi Balogun, a partner at their law firm, Liberty Law, introduces us as she shows me to her office. In there, we (Mrs Balogun and TheWill DOWNTOWN Editor, Onah Nwachukwu) began the hour-plus-long conversation about her tenure as the first female Attorney General of Lagos State, Nigeria.

Members of the Lagos State Executive Council from January 1984 – September 1986

Sitting from Left: Olajide Aleshinloye Williams, Mrs. Hairat Aderinsola Balogun, Air Commodore Gbolahan Mudasiru (Lagos state Military Governor), Mrs. Modupe F.Adeogun, Alhai Lateef M. Olayinka Standing from Left: Prof Ajibade Rokosu, Prof Monsur Akangbe Kenku, Dr. Isaac Olusola Olude, Hamed Olatunde Onipede, Paul Abayomi Awolaja, Tajudeen Adedapo Odofin

You studied at the Lincoln Inn in the UK in 1963, right?

I finished in 1963. I started my studies in 1960.

What was it like as an African woman studying law in a place where there were mostly white people?

Let me go back to the beginning. I left Nigeria at age 12 to attend secondary school in the UK. It was an all-girls school. And this was a private secondary school— so you can imagine, there would scarcely be a black face unless it was the daughter of a king somewhere in Africa or a black country or the daughter of a diplomat.

An ordinary person would not be there, so you wonder how did I get to such a school? There were 250 students, girls, starting from Form 2 till the 6th form. By the 6th form, you are supposed to have done your A-levels. So when I got there, I entered Form 3, Upper 3 is where they put me, but I wasn’t allowed to start school that term because the term had started for a few weeks—the term starts in September—so I was told to come back in January. While I waited, I was sent to a guardian who was to take care of me till I was old enough because that time, you were old enough when you were a 21-year-old.

So I returned to my guardian, who enrolled me with an elderly retired professor to teach me English literature, geometry and algebra. I had not done any of those two because I was only in primary school when I left. So he taught me well, particularly in Latin, and I enjoyed it. School started in January, and I had to face what it was like to be in an all-white environment. Maybe they were looking at me thinking I was a toy and not a real person, so I didn’t have any problems with discrimination.

One day, I didn’t know what we were discussing, and one girl just spat on the floor. I was wild; I hit her. I just stood up and slapped her, and she told the mistress I had attacked her. I was cautioned, and that’s about the only time I encountered anything close to racism. By the time I left school, I was like a celebrity because I got into sports. I wasn’t very good at tennis, but I was good at umpiring, so they made me an umpire. I was also in the netball team, usually as a goalkeeper, and I was very good at it. I was also involved in horse riding and swimming.

Nigerians’ accent back in the day sounded more polished than what we have today, even among uneducated people. What do you think changed?

I think education because education takes you to different environments and a different set of people, and unwittingly, we copy them. The whites were upper class, and eventually, you will start mimicking their tone because you don’t want to stick out differently, so your accent changes. It’s the same with these other people who, by circumstances, are uneducated.

You were 21 years old when you graduated and called to Bar at that young age. Why did you come back to Nigeria, and what was it like practising as a young lawyer in Nigeria?

I came back because the law was passed that any graduate after the 31st of December 1962 had to come and do a Post Graduate practical course of three months in Nigeria, and if you didn’t do it, it would affect your standing at the Bar because the people who have done it are registered, so they will be your seniors. So it was better to return as soon as you’re qualified, do your three months, and get enrolled. If you want to go back, it’s okay.

If you want to get a job, you’ll start. Now, at the Law School, Igbosere, Lagos, in my particular class, there were 57 of us, and I was the youngest— most of my classmates were men in their 50s. So I decided right at the onset when I entered that school that I wasn’t going back for anything. I had done a few weeks of practical courses, and I didn’t want anybody to be senior to me who actually passed the exams after me. So I just decided I would rather practise law. I didn’t want to get a job, even though there was one waiting in the ministry. When we did the exam, we were not graded on first, second, or third classes; it was either pass or fail. But we were told that four of us did excellently well. One of them became the interim president of Nigeria, Earnest Shonekan. The other one became the president of the World Court, Prince Bola Ajibola SAN. Then Akin Delano eventually became a commissioner in Ogun State.

From then, how long did you work before getting appointed as the Attorney General?

I worked from 1967, and I was appointed AG in 1984. It was during the military regime.

First of all, if they knew anything about me, it must be my activity in NBA (Nigerian Bar Association) because, before that time, I had been secretary of the bar for two years, from 1981 to 1982, 1982 to 1983. So at least, I have that administrative (experience). One day, a man came to my office and told me the Governor said I should come and see him. So I went. He asked how long I’d been practising, and I told him. Then he asked what I thought about shooting armed robbers. I told him, “I can’t think about it because I don’t believe in shooting anybody. But the law as it stands now (then at the time), if armed robbers are found guilty, the Governor will approve the judgment, and they will be shot in public with my (the Attorney General’s) consent, and I don’t like anybody being shot.” He said okay and that he thinks we can work together and then gave me my appointment letter.

What would you say is the difference between when you were Attorney General (AG) back then and what it is now?

Honestly, the AGs have become more like servant boys. They try to tailor their advice to what they think their employer wants to hear, and they take the line of least resistance. They are not ready to break any bones or anything. Whereas in those days, whether you are Commissioner for Works, an AG can tell you that you can’t put a road there. You have to do things that will enhance the status of people. The first law we passed was against street trading. Then sanitation. Then trucks carrying sand across the state had to cover it up to stop it from flowing out. Those were the few things that I first drafted. Then I discovered that we had so many cases and not enough Judges.

Actually, during my time, we appointed ten Judges at a go, and I recommended another four before we left, and they were also appointed. We were doing things that really helped the people, unlike politicians. You know politicians want to be important and stay there.

Dealing with the Commissioner for Justice and Attorney General, I think they’ve lost the plot.

They are more like politicians now, they are interested in doing the master’s bidding so they are not removed from office, and everybody wants to stay forever and ever. Even when you try to recommend things to them from the outside, they will never present it to the Governor because they don’t want to ruffle any feathers. They want to stay as long as possible.

So things have not gone very well, but they cannot see it from the inside. When you (others) see it, the reaction is like, ‘do you want their job?’ Even on the appointment of Judges, they(AGs) don’t have much to say about that. I did. I could say, “this person is not fit; I’ve heard from his colleagues, so we’re not putting his name,” because I was the one to make the recommendation to the Governor for him to appoint.

After you left office, you came back to your practice, and you’ve been doing that since then until now, — 81 years old. We are seated here in your office. I spoke to your son, and he says you actually come into the office before him. What motivates you?

Coming in early— I’ve always resumed office at 8 o’clock. In fact, when I went to government service, I used to get there at 7:30am . I’m used to it; I cannot do any different. Getting here at 8:30 or 9am is late, and my morning routine doesn’t provide me time to be late. I get up at 5:30, say my prayers, and bathe. I don’t eat a heavy breakfast, it’s usually biscuits and coffee or banana, and I’m ready. Even if you say forget about the time, why are you still coming to the office at this age? I don’t know anything else. I’m happy doing my job. Yes, I have some frustrations like everybody else, but it doesn’t wear me down; I will still do my best. I keep saying it’s not just for the money. I am trying to develop and support my profession. My first cause is to raise my profession to where it should be.

Lawyers these days are not as distinguished as they used to be.

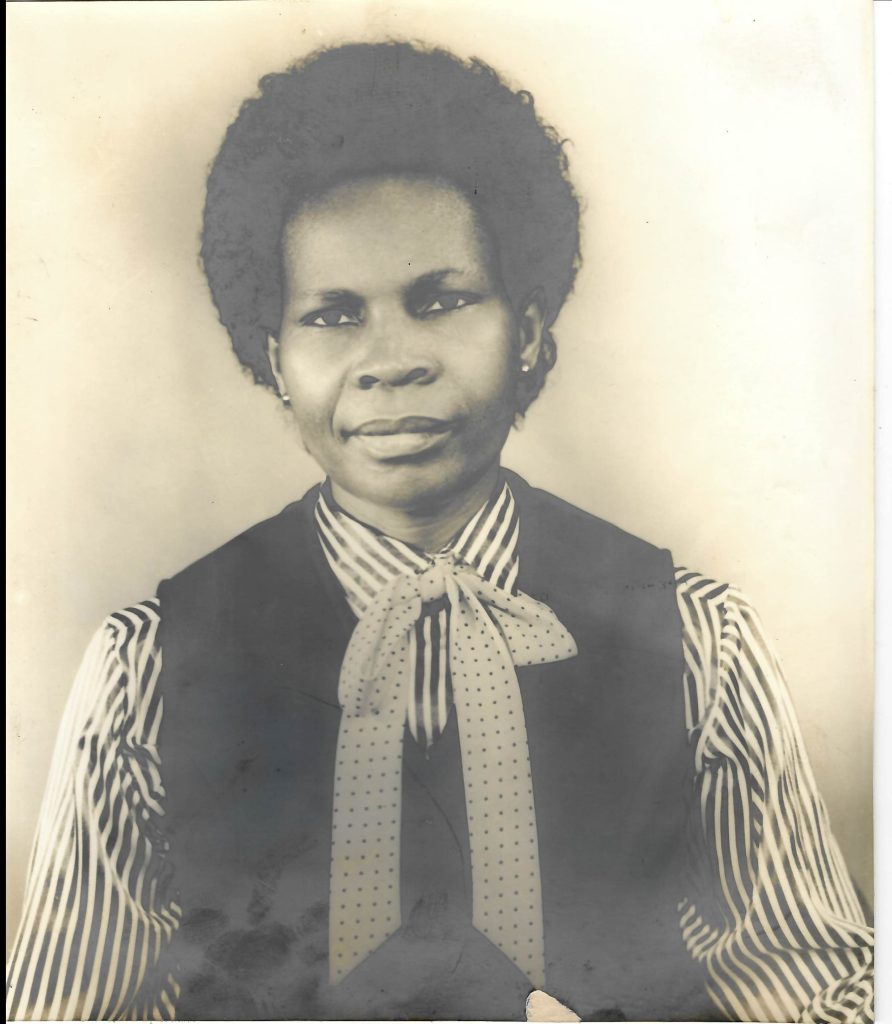

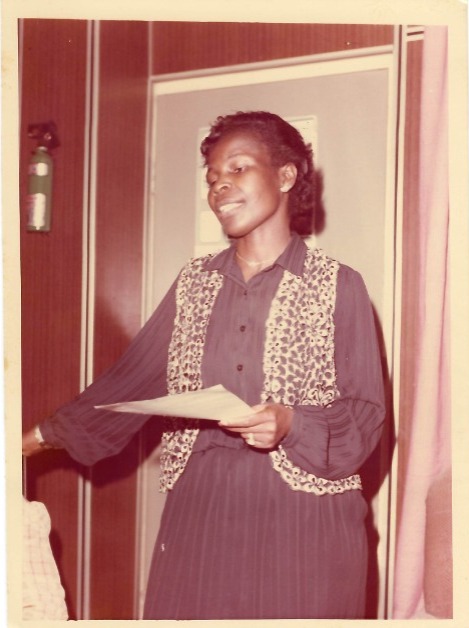

General Secretary of the Nigerian Bar Association (1981 – 1983)

What went wrong, and what do you think we must do to return to that place of respect?

The first thing is money. Most people think once you are a rich man, even when you know that your client doesn’t have a good case, you are able to charge because the man is in serious trouble, but you will not have a good defence. You cannot speak the truth. Justice is based on the truth.

You cannot advance justice and the rule of law if you do not speak the truth. They are thinking too much about themselves, not about the profession. To me, it’s an honour to be a lawyer, and I think that gives me confidence. The day I became a lawyer, my confidence tripled. I could face anybody, even though they were elderly or in high office, and I would say, “excuse me, sir, it is not like that.”

But many of us, because of money and status, they’ve lost it. So we are reducing the efficacy and importance of the profession to the ordinary man, so everything you do now, the ordinary man can do it because you’re not doing the right thing. You hear of judges taking bribes. Yes, we know of some of them because when you read their judgment, you know it’s not according to law; you know something has happened. We hear stories of some judges writing two judgments and giving them to the highest bidder.

And, of course, the public that you are serving knows. They tell each other. That’s why we have the nickname lawyers are liars. I worked with Olusegun Obasanjo in two different capacities. I am the first lawyer in Independent Corrupt Practices Commission(ICPC). My colleague, Mr Akin Delano and I actually drafted the ICPC law. But they amended it to something else.

Attorney General and Commissioner for Justice of Lagos State Jan 1984 to Sept 1986

What would you say is a legacy you would like to leave behind?

I think the only legacy is somebody who served in truth and justice— that’s what I titled my memoir. You must have confidence that this is the truth as you see it, as you know it; no matter who it offends, you do your best according to the law of the land. Sometimes, the law may be mistaken, so you do justice as far as is humanly possible to everybody on the same level.

Everything is firmly based on justice and truth because, in the end, if you do otherwise than truth, the moment truth comes out, everything is finished. Let’s talk about mentorship. Do you have a mentorship programme?

We have one now formally with the Law School. Three other lawyers and I had a session last year, and we’re very happy it was successful.

The students enjoyed it, and we will repeat it. Generally, people think they know it all and don’t want a mentor, but we went out of our way to talk to a mentor back then. You can never know it all, and the people at the start know a little bit more. That is why we mentor. We can sift and get the best out of them. It’s like a baby; even to start eating, somebody has to teach a baby how to eat. I have no regrets that I purposely attracted a mentor, and she served me well. If anybody thinks I’ve passed something on to them, I’m happy to hear about it.

Receiving National Honour of OON

A lawyer by training, Onah packs over a decade of experience in both editorial and managerial capacities.

Nwachukwu began her career at THISDAY Style before her appointment as Editor of HELLO! NIGERIA, the sole African franchise of the international magazine, HELLO!

Thereafter, she served as Group Editor-in-Chief at TrueTales Publications, publishers of Complete Fashion, HINTS, HELLO! NIGERIA and Beauty Box.

Onah has interviewed among others, Forbes’ richest black woman in the world, Folorunso Alakija, seven-time grand slam tennis champion, Roger Federer, singer Miley Cyrus, Ex Governor of Akwa Ibom State, Godswill Akpabio while coordinating interviews with Nigerian football legend, Jayjay Okocha, and many more.

In the past, she organised a few publicity projects for the Italian Consulate, Lagos, Nigeria under one time Consul General, Stefano De Leo. Some other brands under her portfolio during her time as a Publicity Consultant include international brands in Nigeria such as Grey Goose, Martini, Escudo Rojo, Chivas, Martell Absolut Elix, and Absolut Vodka.

Onah currently works as the Editor of TheWill DOWNTOWN.