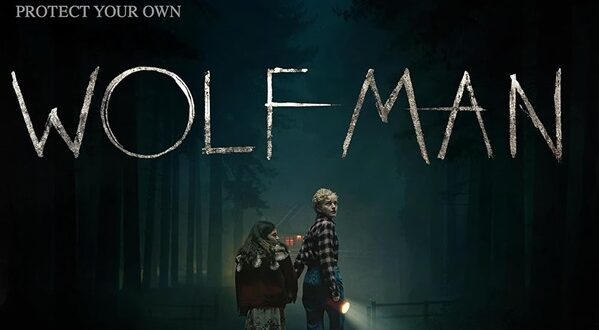

Movie Review: Wolf Man

In the latest remake to tear into a classic from the Universal Monster franchise, Wolf Man can’t find its tail. It has its head. It eventually grows some teeth, but its back end is suspiciously cut short. For that matter, its belly is also a little empty, a product of a meatless plot that certainly wouldn’t sustain the beast for the one short night over which the film is set. Attempting to distinguish itself in a genre within a genre that has a long and illustrious history, Wolf Man doesn’t care about abiding by any werewolf lore. Don’t expect shots of clouds grazing past a full moon or an immediate transformation that rips the clothing right off the unsuspecting newly-bitten.

There is intention behind this new iteration, and that’s completely due to writer-director Leigh Whannell. He’s written some of the most memorable horror franchises of the past 20 years, like the sadistic horror film Saw and mind-bending supernatural thriller Insidious. Five years ago, Whannell wrote and directed The Invisible Man, a modern adaptation of the 1897 science fiction novel written by H.G. Wells. (It was also adapted into a classic film by Universal in 1933.) Whannell’s version, which had the unfortunate luck to release in February 2020, told a scary story, but it also coursed through modern audiences with a horrific, though timely undercurrent. It used the genre to illustrate how gaslighting and domestic violence can destroy a woman when the monster, her partner, is in control of what people see of him and what they don’t.

Like The Invisible Man from 2020, Wolf Man is better when the story’s underlying metaphor shines through. Whannell tackles another form of abuse in this film: generational trauma. He is particularly interested in how we pass on the curse from parent to child and how it takes incredible strength and fortitude to break it for the incoming generation. Christopher Abbott stars as Blake, an unemployed writer who’s at home full-time with his young daughter Ginger (Matilda Firth). His wife Charlotte (Julia Garner) is a busy journalist, and their life together has become mechanical.

That is why when Blake receives a letter from the state of Oregon that his missing father has been deemed legally deceased, the opportunity to reconnect and change up their routine is too good to resist. They pack up and take off to a remote part of the state where Blake was raised. His was a difficult upbringing; one in which his father (Sam Jaeger) prepared him for life off the grid. In their part of Oregon, heavily forested and teeming with wildlife, there are rumours of a hiker who went missing and gained the “face of a wolf.”

Don’t expect more backstory than that. There is no creation history or origin story. Whannell doesn’t even bother to give viewers a sly hypothesis as to where the disease could have originated, a point that is both mysterious and coy, as well as frustratingly opaque. The film also doesn’t fit nicely into our long-imagined beliefs on werewolves. These beasts don’t transform on a full moon; in fact, once you’ve transformed, it appears that is your only state of being. You’ve been changed, and there is no going back.

To return to that theory that’s been proposed here, generational trauma is certainly something that, likewise, never leaves you. You can work on yourself. You can only fight the urge to allow it to rule your way of life. And that is what happens to Blake. The family doesn’t make it to his childhood home before their truck crashes, and they are fighting for their lives against a strong, fearsome opponent who, like the shark in Jaws, is teased endlessly but who gets very little dedicated screen time. The idea of it circling the house, honing in on its prey, all the while a new shark is threatening to emerge – is what will have most hooked at least enough to wonder what will happen next. Nursing a bloody, injured arm, Blake begins to notice changes immediately upon entering the house that raised him, and one that likely left him with unresolved emotional turmoil.

Like most of Whannell’s work, there is some blood and guts, though don’t expect anywhere near the level of grotesque depravity that became a tentpole in the Saw series. Blake’s transformation is not quick, but the gross factor is almost worse in its suspended state. The demarcations from one stage to the next are heartbreakingly identifiable by the new teeth that squeeze into his mouth or the padding that appears on his cheeks. The majority of the film takes place in this one night that feels too long to be just a few hours from crash to resolution, though there are very few moments of stillness. Viewers wanting jump scares and foreboding music will have enough in Wolf Man, but those who are expecting a repeat of Whannell’s smart script and sophisticated handling of The Invisible Man will find that the satisfying think piece has been eaten up by a different beast altogether.

5/10

Boluwatife Adesina is a media writer and the helmer of the Downtown Review page. He’s probably in a cinema near you.