Movie Review: The Substance

Mirror, mirror on the wall—why don’t you leave me alone?!

As beauty standards soar to unattainable heights, the mirror is often a reminder of how we measure up to the world. Standing face-to-face with your mirrored image, it is too easy, almost enticing, to scrutinise imperfections. And now, the pursuit of “perfection” is fueled by an ensemble of substances from Botox to Ozempic that push people—particularly women—to probe their self-image. That’s business as usual, sold as a chic and sexy enhancement to everyday life. And if that wasn’t enough, the mirror has jumped from the confines of our homes into our pocket-size parasites that can document every change instantaneously.

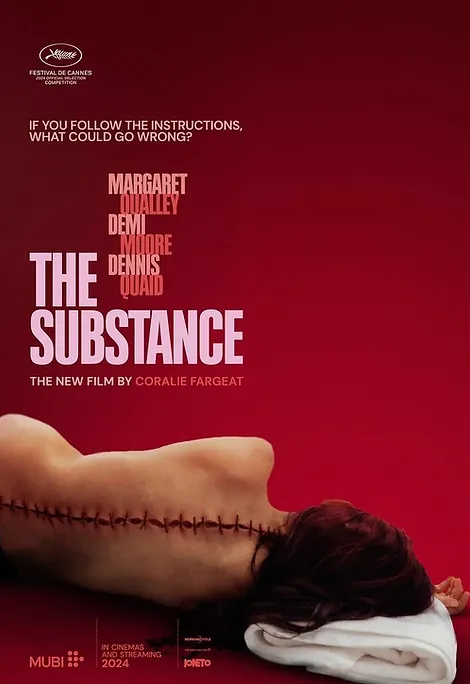

Many of these anxieties come hand in hand with growing older. That’s the case for Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore), a fading Hollywood icon and the star of a popular TV aerobics program. One of Fargeat’s many heavy-handed decisions is to open The Substance with a time-lapse of Elisabeth’s Hollywood star on the Walk of Fame, tracing it from its inauguration to its present weathered state, smeared with spilt fast food. This cynical view of fame is candid, kickstarting the movie with a ready-made sense of desperation.

So, when Elisabeth is fired on her 50th birthday by Harvey (Dennis Quaid), a grotesquely apt (and appropriately named!) embodiment of an industry rife with male chauvinism, we really feel just how fleeting fame can be. Fargeat’s direction in this scene is unflinching, capturing Harvey in an unflattering close-up shot as he crudely chomps down on a bowl of shrimp while dismissing Elisabeth for ageing out. Here, Fargeat quickly establishes just how crucial the camerawork will be in implicating the characters—and the audience’s gaze.

Elisabeth leaves the one-sided lunch date only to be rammed in her car moments later. Miraculously, she survives without a scratch. At the hospital, a modelesque nurse with bright eyes informs her that she’s an ideal candidate for treatment, handing her a flash drive containing information about the titular “Substance.” In an almost dreamlike sequence, Elisabeth discovers an opportunity that promises to rejuvenate her cells, ostensibly allowing her to become a younger, hotter version of herself. However, this opportunity presents a Faustian dilemma, where the cost of reclaimed youth might be far greater than it appears.

Injecting the neon-green Substance inside her arm, Elisabeth falls to the floor, where her body mutates and moves. This is where the body horror kicks off and doesn’t stop: Elisabeth’s back splits down the spine, and another body emerges, covered with viscous liquid and blood. Enter Sue (Margaret Qualley), a younger, smoother version of Elisabeth who radiates confidence and charm. Elisabeth and Sue are bound to a cycle in which each must regenerate in solitude while the other lives in the outside world, swapping places every seven days. This routine is governed by the directive: “Remember you are one.”

What makes The Substance work is just how persistently self-aware Fargeat is. She portrays Moore’s Elisabeth fluctuating between bouts of compassion and anxiety-inducing mania. In both cases, these moments are undeniably private. On the other hand, Sue is a beacon of youth and beauty, and Fargeat directs her point-blank at the audience. It’s how we understand an influencer’s Instagram persona. Her first scenes are portrayed in an objectifying manner so stark that they place directors known for their male gaze in the hot seat—think Scarlett Johansson as Black Widow in the Marvel movies, Megan Fox in Michael Bay’s Transformers, or just Zack Snyder generally.

While Elisabeth spends her allotted weeks alone in the apartment watching TV and stirring in her depression, Sue auditions as the replacement for the TV aerobics show. It’s here that Fargeat makes the extent of Hollywood’s sexism abundantly clear. Swells of mediocre men decide who and what is beautiful. Sue is placed on a pedestal, while Elisabeth is forgotten—a vicious irony. It’s nothing new. Still, Fargeat confronts these hypocrisies with such intensity that it magnifies their absurdity, exposing them with unflinching clarity through the frenzied behaviour of the film.

As Sue’s fame skyrockets, an increasingly reclusive Elisabeth begins to harbour resentment toward her other half. This delicate balance eventually collapses, leading to a struggle for dominance that draws its intensity from the internal psychological violence of Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan (2010) and the all-consuming vanity of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. Varied acts of defiance against one another amplify the inner (now external) conflict until Sue, enticed by the fame and fortune that follows her youth, decides to abuse the seven-day rule for months—a temporary solution with ultimately dire consequences.

A struggle for dominance in a tale about the dichotomous self is as old as the concept of vanity itself. That said, each iteration brings its own nuance. Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous tale of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde splits the pristine version of ourselves according to societal expectations with our undying repressed desires. Black Swan probes the conflict between perfectionism and impulse. The Substance presents a resonant schism, amplifying the fear of decay and the desire for beauty found in Dorian Gray for the modern age, rendered with hot-blooded, unforgiving intensity. We are all implicated in participating in this vain media engine, where “in with the new and out with the old” dictates our ideas of self-perception and perfection. Social media has halved our half-life. We have never felt the looming sense of decay more.

Much of The Substance unfolds in Elisabeth’s sterile bathroom—a pronounced contrast to the lurid colours in sunny Los Angeles and the production studio where Sue’s new flashy exercise show takes place. Here, Fargeat has us confront the two individuals without distraction. The reflections of both Sue and Elisabeth in the bathroom mirror emerge as their own antagonists.

Let’s be clear—there’s nothing unkind to say about Demi Moore’s appearance. Yet, Elisabeth struggles with her reflection—a backscatter of boiling insecurities rather than anything physical. However, as Sue begins to face the consequences of her insatiable vanity, particularly forgetting that she and Elisabeth are one, her external beauty starts deteriorating in a gruesome fashion. Her ensuing desperation propels us into Fargeat’s final act, where Sue and Elisabeth morph into a Frankensteinian monstrosity, a composite of their physical anxieties multiplied by a million.

Every moment of Fargeat’s 141-minute run-time builds anticipation—for what, we’re not sure at first. Yet the urgency felt by both Sue and Elisabeth gives us no choice but to bask in the film’s high-octane movements. A bloodbath is the film’s final reprieve after a conflict that cycles from decay and rebirth to decay all over again. Its lasting irony is how oblivion becomes preferable to fame and perception. But, more than anything, The Substance is a grim reminder that when we approach the mirror, we bring more than just our reflection; we carry our vanities and insecurities, all bundled into one monster. To divorce them rather than work to make amends is disastrous. It’s as straightforward as the moral taught by the Evil Witch from Snow White. The true horror is stoked when you seek to become the answer to the question: “Mirror, mirror on the wall, who’s the fairest of them all?”

9.5/10

Boluwatife Adesina is a media writer and the helmer of the Downtown Review page. He’s probably in a cinema near you.