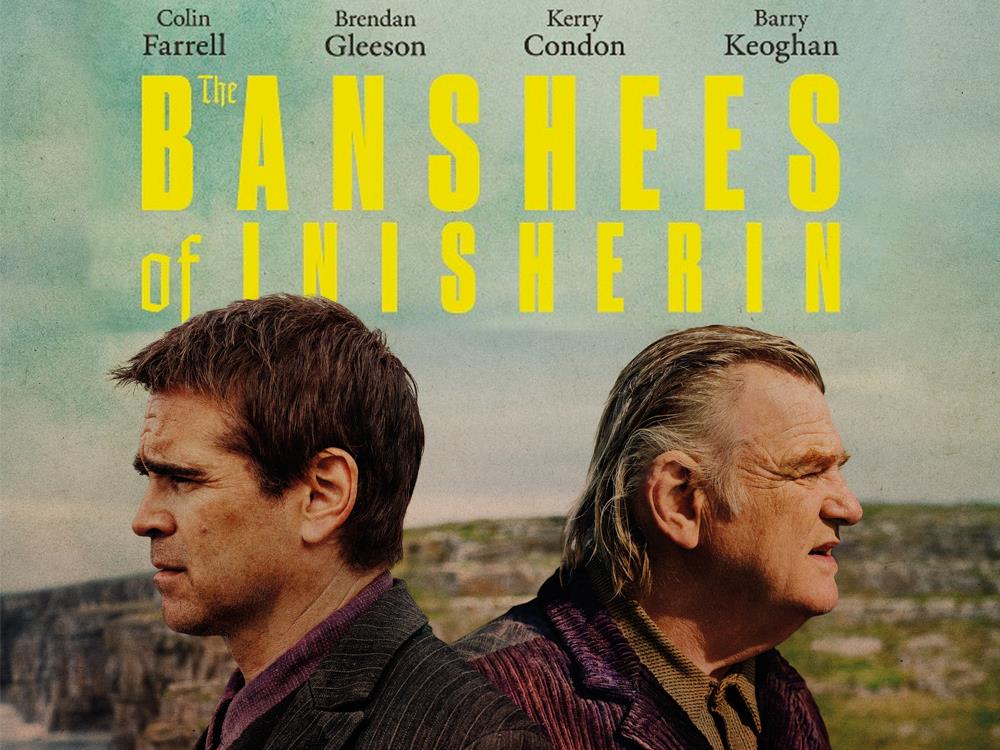

MOVIE REVIEW: The Banshees Of Inisherin

Directed by: Martin McDonagh

Starring: Colin Farrell, Brendan Gleeson, Barry Keoghan, Kerry Condon

Film length: 1hr 49m

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, the last film to be written and directed by Martin McDonagh, won Oscars, BAFTAs and Golden Globes galore. McDonagh could have used that success to bag himself a Marvel blockbuster or some other lucrative Hollywood extravaganza, but instead, he has gone the opposite way. His new film is a low-key, small-scale black comedy that hinges on an absurd disagreement between two seemingly decent men on a tiny island off the coast of Ireland. It’s more theatrical than McDonagh’s previous films, but that’s not a criticism. The Banshees of Inisherin may get its dark power from perfectly delivered, finely honed dialogue rather than splashy violence, but it’s as gripping as anything he’s ever done.

Colin Farrell and Brendan Gleeson, the stars of McDonagh’s terrific debut film, In Bruges, play two friends, Padraic and Colm, in The Banshees of Inisherin. The year is 1923 – although you get the sense that the rural island of Inisherin hasn’t changed in decades and probably won’t change for decades. Padraic, played by Farrell, is a simple soul who tends to a few cows, a pony and a beloved miniature donkey and shares a sparse cottage with his bookish sister Siobhan (Kerry Condon), who clearly is the brains of the family. He’s first seen strolling along the island’s country lanes, between its dry-stone walls and apparently empty fields, until he reaches Colm’s cottage. The exotic masks and models hanging everywhere suggest that Colm dreams of a world beyond Inisherin, and Colm’s scowls suggest that he is depressed that those dreams haven’t been realised (not many actors can scowl more ferociously than Gleeson). But all Padraic cares about is going to the pub. After all, he says, it’s already two o’clock in the afternoon. McDonagh follows this punchline with another: Colm’s clock immediately strikes two, which shows how obsessively punctual Padraic can be. In just a few moments, we’ve learnt that the men spend too much time drinking together, that their routine has been going on too long, and that Padraic is the keener of the two to keep it going.

When Colm finally trudges to the gaslit, clifftop pub, he insists that Padraic sits elsewhere. “I just don’t like you no more,” he declares. Besides, with old age approaching, he wants to devote his days to writing and playing folk music on his violin – not listening to Padraic prattling on about donkey droppings. Padraic, played with heartbreaking innocence by Farrell, is hurt and baffled by this sudden break in a longstanding friendship, but rather than offer any further explanation, Colm presents him with an ultimatum: every time Padraic talks to him, he will chop off one of his own fingers. No one is quite sure if he means it, but this being a McDonagh film, it’s entirely possible that he does. Will Padraic have the self-control necessary to leave his former pal alone?

The hints of mysticism and the slow, insistent rhythms turn these two stubborn former pals into mythical figures: timeless embodiments of the masculine, self-destructive refusal to be reasonable.

It’s such a jaw-dropping premise that McDonagh could have thought of the bizarre chopping-off-my-own-fingers threat and built his screenplay from there. Certainly, he doesn’t take the plot much further. There are subplots concerning Siobhan’s issues with the provincial small-mindedness of Inisherin, and there is some tragicomedy concerning a not-too-bright policeman’s son, played by Barry Keoghan: both actors are excellent. But the film keeps its focus on the feud between Colm and Padraic, the question of whether being a creative artist is more worthwhile than being a “happy lad”, albeit a “dull” one, and the idea that the two men’s intransigence might shed some light on Ireland’s Civil War: the characters often see and hear cannon fire on the mainland, just across a strip of water, but no one knows who’s fighting or why – and no one cares.

The Banshees of Inisherin is quiet, steadily paced and slightly repetitive, but it’s always compelling, and it eventually grows hauntingly sad. McDonagh doesn’t stint on daft jokes and jovial banter, but his film gets bleaker, stranger and more poetic as it goes on until it feels as if the men’s pointless falling out has broken something important and that things can only get worse for them, the island, and the world.

The refreshing part about The Banshees of Inisherin is how different it is from most other films, including McDonagh’s own. It has the ring of a tall tale that has been told in pub after pub, gathering weird new details every time until it has become a part of Irish folklore. It’s a story you’ll want to hear and tell again and again.

8.5/10

Boluwatife Adesina is a media writer and the helmer of the Downtown Review page. He’s probably in a cinema near you.