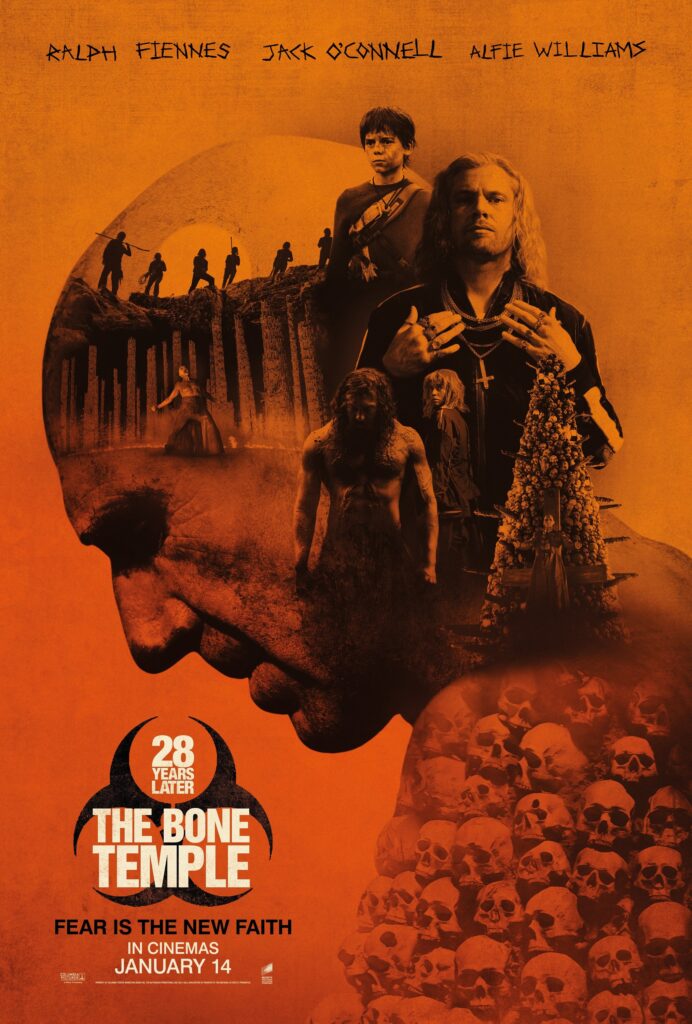

28 Days Later: The Bone Temple

In Nia DaCosta’s 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple, zombies are the least scary thing lurking in the postapocalyptic wilderness of England. Sure, the “rage” virus infects people, making them want to violently eat flesh and rip innocents from limb to limb — but at least it’s a known quantity. Humanity, with its propensity for cruelty, dishonesty and evil, however, is much more of a dangerous unknown.

That danger and how humanity can account for its mistakes is what The Bone Temple is most interested in exploring. Rather than focusing on the relentless hunger of the zombies, the film instead turns its gaze to the people who have carved out a life in the hellscape of a virus-ravaged England and how they often pose a greater threat to one another.

The evilness of the times is deftly encapsulated by Sir Lord Jimmy Crystal (the wickedly frightening Jack O’Connell), an unhinged gang leader with a love of gold jewellery and sadistic torture. The Bone Temple picks up mere moments after its predecessor, 28 Years Later, left off with Spike (Alfie Williams) being forcibly taken in by Jimmy’s murderous cult-like gang. Donning blond wigs and velveteen tracksuits, Jimmy and his “fingers” (all called Jimmy) roam the English countryside terrorising enclaves of survivors with perverse acts of “charity” to absolve them of their sins.

Their violence is reminiscent of Alex and his droogs from A Clockwork Orange — extreme and deeply sinister. In the gang, Spike tries to retain some semblance of benevolence to survive, finding solidarity with member Jimmy Ink (Erin Kellyman), who seems to doubt Jimmy’s claims that he is the son of Satan. DaCosta leans into the graphicness of the gang’s terrifying techniques, depicting the torture scenes with a focused, unflinching viscerality that feels all too real.

On the other hand, the film also follows kindhearted Dr. Ian Kelson (a fantastic Ralph Fiennes), who serves as a foil to the Sir Lord’s barbaric ways. The Bone Temple he spent years building, the doctor says, is a memento for the infected and uninfected dead. It gives a real scale to the lives lost during the outbreak, blending the bones of human and zombie alike, underscoring Ian’s belief in the inherent goodness of all souls.

That belief is further strengthened by Ian’s connection to Samson (Chi Lewis-Parry), the Alpha of a nearby infected clan who Ian named and learns has a taste for morphine, which seems to quiet the rage virus. As the two develop their bond, taking morphine and listening to the doctor’s old vinyl records, the doctor believes he might see a light at the end of the tunnel for the infected.

“Do you have memories?” Ian rhetorically asks Samson at one point. “A trace of what you once were?”

It’s a question that could be extended to any of the other characters who managed to survive the initial outbreak and have hardened themselves over the years to one another and themselves. While Ian and Jimmy vaguely remember a world before the virus took over, the young adults who surround them know only the Mad Max-like postvirus society where fear reigns supreme.

In light of that, the movie asks what really makes us human: Is it our ability to change? The ways we inflict the harm we’ve received onto others? Or how we enjoy the breeze in the trees? That line of inquiry pays off when the two storylines finally converge in an ecstatic climax that sees every character grappling with their own idea of salvation and redemption.

Director Nia DaCosta took the reins from original director Danny Boyle, starting the shooting of The Bone Temple just after 28 Years Later wrapped production. The film shifts away from Boyle’s frenetic, punk shooting style and editing, with DaCosta and cinematographer Sean Bobbitt incorporating longer shots into the mix, reflecting the psychologically penetrative aspect of Alex Garland’s script. Her style, which I first encountered in 2021’s Candyman remake, fits the less frenetic, more introspective nature of the screenplay. Still, DaCosta takes some big stylistic swings — particularly with the soundtrack — that sometimes make you feel as if you’re watching a comedy rather than a horror film. It’s a welcome, offbeat balm to the more intense moments sprinkled throughout and reflects the movie’s more pondering approach to a story that questions who the real monsters are.

8.5/10 It’s Great!

Boluwatife Adesina is a media writer and the helmer of the Downtown Review page. He’s probably in a cinema near you.