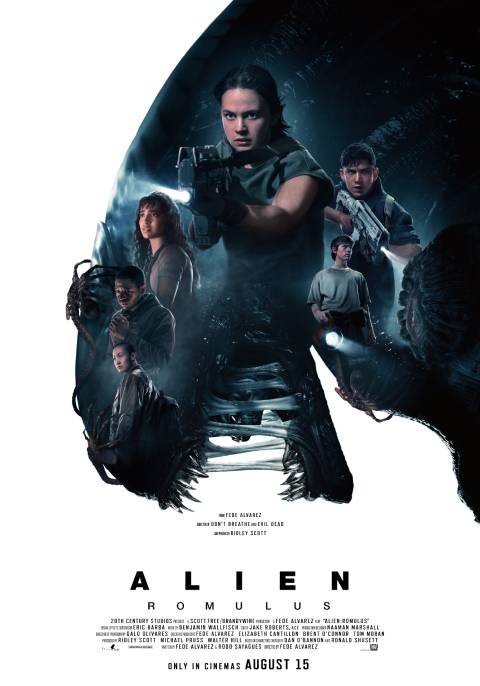

Movie Review: Alien: Romulus

Forty-five years after Alien launched horror into space, there’s little that hasn’t been analysed about its hissing xenomorphs, face-huggers or the lingering untrustworthiness of “synthetic persons.” These ideas recycle endlessly through a franchise that is ever expanding, like space itself, but the metaphorical power of the 1979 original and its 1986 (and much more conventionally exciting) sequel, Aliens, still inspire appreciative analyses all these decades later.

Ridley Scott didn’t intend for any of that when he set out to direct the first film. He wasn’t even the first choice for the job. But, according to him, he won it by pitching “the most straight-forward, unpretentious, riveting thriller like Psycho or even the most brilliant B-level like Night of the Living Deador Texas Chainsaw Massacre, but I want it to look, and I’m going to do this, like 2001: A Space Odyssey.”

A scary movie, in other words, except in space. Where no one can hear you scream.

Alien: Romulus director and co-writer Fede Álvarez honours that conceptual seed in mood and feeling, dispensing with the allegorical fright in favour of taut, pulse-pounding standalone adventure bumping with legitimately earned jump scares.

It is also consciously merging the universe’s greatest hits, incorporating cues from James Cameron’s Aliens and the crimes against nature seen in Alien: Resurrection and the stoic, mythology-expanding prequels. By some miracle, Álvarez weaves all this into the plot without it deteriorating into a mess of cliches or “don’t go in there” stupidity . . . if you don’t count the entire reason we’re setting out on this adventure.

Imperfect though Romulus may be, it’s also a solid entry in a franchise of films whose original maker has taken the extended story seriously enough to petrify it.

Álvarez returns us to the simple sweatiness and anxiety that made Alien magnificent, paying homage to its basic realism and the timelessness of corporate exploitation. It’s easy to forget that this franchise began with a crew of grumpy underpaid space truckers having an assignment beyond their scope of expertise forced on them by the undercover android embedded with their small team.

The 20-somethings signing themselves up for trouble in Romulus choose their doom, but only because their circumstances leave them with few other options. But they are a similar breed of working-class survivours exploited by Weyland-Yutani, the intergalactic mega-conglomerate chasing an annihilative parasite across space and time.

Romulus is set between the events of Alien and Aliens, two of the four movies built around Sigourney Weaver’s Ellen Ripley and everything her corporate overlords stole from her: motherhood, stability and plain old peace.

Somehow Weyland-Yutani makes life worse for the 20-somethings trapped in its Jackson’s Star mining colony. They and their families are expendable indentured servants on a rock enrobed in perpetual darkness. Cailee Spaeny’s Rain Carradine, having lost her parents to lung disease, is one of the many who dream of sunlight she’s never felt on her skin.

All Rain has is her adopted brother Andy (David Jonsson) , an obsolete android programmed by her late father to protect her. He becomes her ticket off-world when a group of her old friends, including her ex, Tyler (Archie Renaux), and his sister Kay (Isabela Merced), hatch a plan to misappropriate a work vehicle, scavenge a few hyper-sleep pods off a derelict vessel they picked up on their scanners, and take off for a better life many light years away.

Andy is the only one that can interface with the ship’s system. Rain is leery of the scheme, which is only accentuated by the nonchalance with which Tyler’s boneheaded buddy Bjorn (Spike Fearn) and their pilot Navarro (Aileen Wu) try to sell her on it. But the chance to escape for sunnier climes is too tempting to pass up.

This is the ground floor of any “house of horrors” flick. Álvarez directed a capable update of one of the best of that genre with 2013’s Evil Dead, followed by Don’t Breathe, in which he soaks long silences in dread.

And that is what we have in Alien: Romulus– a good time that drives like it’s on rails but slows down the action to steep us in fright. I have seen every Alien movie there is, including the Predator crossovers, and Romulus is the first in a long while that managed to jolt me a few times.

Compared to the slick faux-wetness of the computer graphics xenomorphs in Alien: Covenant, these props amplify their menace in ways that don’t translate as well via pixels. That said, one particularly imaginative sequence involves a digitally rendered peril utilising a known aspect of the xenomorphs in a new way, a tough feat in a franchise as well-trodden as this.

The film’s strongest game is its homage factor, especially in the way it captures much of the original’s claustrophobia. Their vessel’s closed quarters and the space station’s relentlessly dim flooded rooms, along with the ominous disrepair of its metal bridges and maze of hallways. Deep within awaits another resurrection of sorts that’s worth appreciating for the effort more than the execution.

Put simply, it feels like a classic Alien movie for the best reasons while lacking the thought-provoking and soulful weight of the best of them. Since the notion of “best” is subjective, for our purpose let’s say Alien and Aliens set the bar – although, for superfans, there is no such thing as a truly bad alien movie.

The first three Alien films are the journey of Sigourney Weaver’s Ellen Ripley, through whom the story expands to look at the ferocity of motherhood, among other things, along with the closed-in cheapness of life in a universe ruled by corporate profiteers. They’re also about the loneliness of inevitable defeat and what it means to be one person against an evil designed to outlast human will.

That, I think, is the major shortcoming of Alien: Romulus; there is little in the way of an emotional hook and no sign of an intellectual one. There are explanations without meaning: Its space station death trap is divided between two sides, one called Romulus and the other Remus, after Rome’s foundational fable, without leaning into the why of it.

We’re also left to wonder what this movie is really about besides further establishing Weyland-Yutani’s inhumanity which, OK, we get it. That leaves us with . . . what? It’s about family in the same way the Fast & Furious franchise is about family. You could also say it’s about desperation, but ultimately what horror movie isn’t?

None of that negates its worth as a good time. I’m only saying it works best if you don’t think too much about it beyond appreciating a couple of outstanding performances.

Jonsson, a familiar face from HBO’s Industry tops that list with a performance that shifts between a glitchy, affectionate simpleton whose only purpose is to protect his sister until, inevitably, circumstances upgrade him to meet the enemy on its level.

Performing two convincingly different Andys with separate motivations lends a note of welcome ambiguity to a premise that always boils down to a process of elimination. Andy also gives purpose to that other detail to which I’ve alluded to beyond the mere wow factor of how far Computer Generated Images have come.

But if the franchise were to be renewed for a new generation it needs a Ripley equivalent more than an Andy, leaving Spaeny to float into that inky void.

They are not the same, neither is Spaeny trying to be, which is wise. But if there is a motivating subplot aside from a tangible device that could justify a continuation, it simply isn’t present.

Instead, Álvarez and his co-writer Rodo Sayagues circle back to familiar endgame propellants that don’t make sense for reasons other than calling back to previous movies (set in timeframes that haven’t happened yet in-franchise. . . ). One is simply ridiculous. As for the other, let’s just say that there is no Jonesy the cat in this movie, so they shove someone into that role . . . and it’s ill-fitting.

Álvarez and Sayagues may have also thought about fan service with these moves, but they only highlight their lack of imagination or unwillingness to dream up a new escape plan. Of course, the reason we keep getting new Alien movies is that its monsters are inescapable. One can only depart from so much before returning to what works, which typically involves vacuuming the offender into deep space. I’m happy to say other movies in this franchise deserve that fate more than this one, although let’s pray someone maps a less predictable route for whatever chapters come next.

7.2/10

Boluwatife Adesina is a media writer and the helmer of the Downtown Review page. He’s probably in a cinema near you.