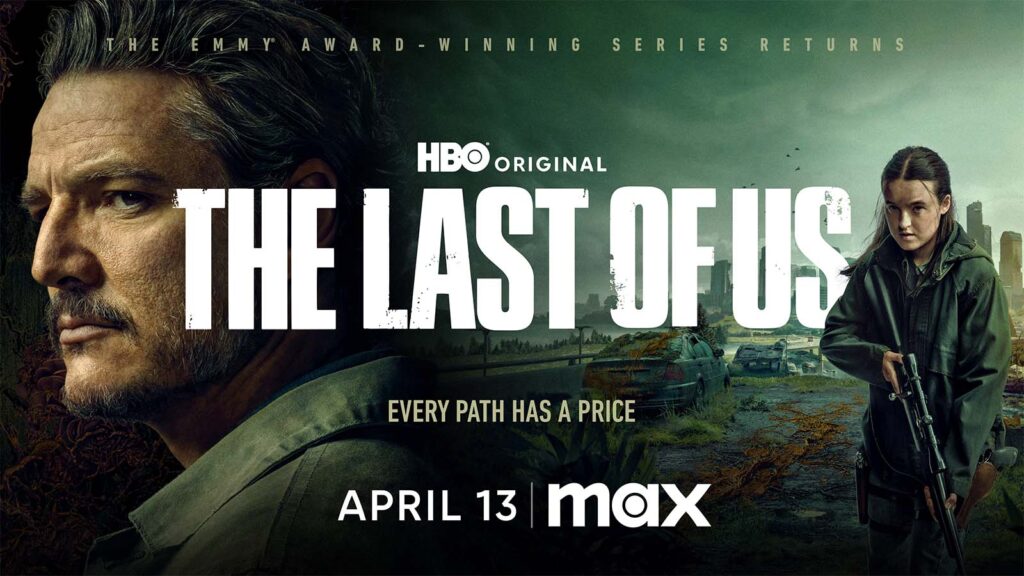

Watch of the Week: The Last of US Season 2

The first season of HBO’s The Last of Us, which premiered in 2023 to great acclaim, looks best in contrast to something else. It’s a sombre, scary zombie apocalypse drama, but it is not The Walking Dead. The latter show’s aggressive nihilism is nowhere to be found in the first season of The Last of Us, Craig Mazin and Neil Druckmann’s adaptation of the popular video game. Darkness looms over everything, but hope and humanity seep in through the cracks. The season takes long detours to flesh out the personhood of side characters and is warmed at the centre by the deepening bond between Pedro Pascal’s Joel and Bella Ramsey’s Ellie.

It’s good TV, building upon what was considered one of the more literate, narratively sophisticated video games of its era. The second game was a bit less critically acclaimed, and so it stands to reason that season two of the television series should suffer the same fate. Alas, it does. Suspense and intrigue abound, but the new run of episodes feels too much like a mere dystopian survival adventure. Much of the grace, nuance, and texture of The Last of Us’s first go-round is missing.

There is some effort to repeat the season-one formula. New characters are explored in flashbacks and brief digressions. We meet a grizzled faction leader played by Jeffery Wright; another, quite thrillingly, played by Alanna Ubach. In the relative peace of the walled hamlet of Jackson Hole, where Joel and Ellie have settled five years after the action of the first season, Ellie has a love interest, Dina (Isabela Merced), and Catherine O’Hara plays a weary therapist with a sad past. (Which I guess isn’t saying much—everyone on this show has a sad past.) There is also a complicated new antagonist played with alluring fire by Kaitlyn Dever.

The cast all have their moments, and their presence does help conjure up some of season one’s sense of epic-novel expansiveness. But season two is largely focused on one mission, which takes the show to a crumbled Seattle, where a war rages between a brutal militia and a religious cult that has reverted to the old ways of bows and arrows. The ornate violence of these two groups is heavily reminiscent of The Walking Dead, a show that grew ever more operatically gruesome the further it progressed. I hope that is not the fate of The Last of Us, but season two gives us some reason for concern.

Of course, this is a zombie show we are talking about, and thus some violence is to be expected. It’s possible that my issue with season two is just general post-apocalypse fatigue; at some point, all the overgrown cities and trauma-hardened warlords blend together. Maybe it’s unfair to criticise The Last of Us for only doing what comes naturally to its genre. But season one managed to be something distinct and special. This season’s group of murderous fanatics—who, in Walking Dead fashion, are perhaps more dangerous than the zombies—seems awfully familiar in comparison.

There are some developments creeping up that may prove interesting in season three—the plague seems, in some terrible way, to be evolving. But by the end of season two—an abrupt cut to black that frustrates more than it tantalises—all that is still a ways off. What’s come before has been entertaining enough, but rarely as stirring and enveloping as season one.

It’s also possible that these new episodes are hampered by something I shouldn’t spoil here—though fans of the video game (or fans of reading plot descriptions of video games) will know exactly what I’m referring to. When that series of events does arrive, the season takes harrowing shape. It’s an effective shock, so effective that the show struggles to move past it for the rest of the season. An emotional flashback episode eventually attempts to close the loop; I suspect it will be the most lauded hour of the season. But it is static and isolated, a revisiting of an irretrievable point in the show’s past. It doesn’t carry us toward an exciting future.

Maybe that will be the job of season three, and these episodes are a mere bridge between grand narratives. But eight hours is a lot of time to devote to the in-between. That kind of stalling is not unlike wandering around Georgia for years, hoping Rick and company will finally take us somewhere new.

Boluwatife Adesina is a media writer and the helmer of the Downtown Review page. He’s probably in a cinema near you.