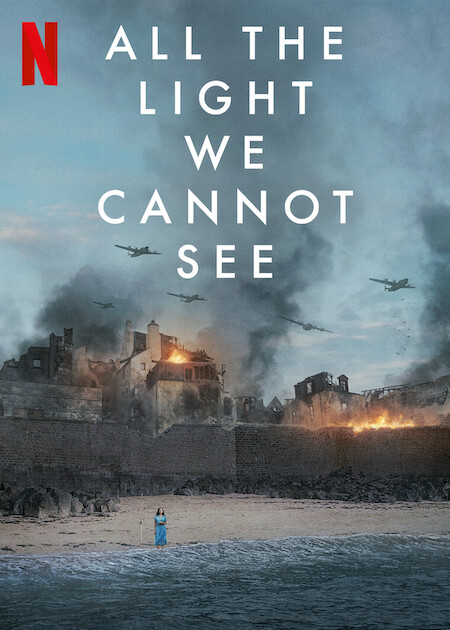

Watch Of The Week: All the Light We Cannot See

Some books should stay on the page.

Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See was published in 2014 to critical and commercial success, winning the coveted Pulitzer Prize for fiction. It tells an introspective, morally complex, and lyrical story about German-occupied France near the end of World War II.

Unfortunately, much is lost in translation when Light makes the jump to Netflix for a four-episode miniseries. However transcendent the book, the show is a flaccid, fancy failure, with beautiful production values glossing over poor storytelling and acting. When it tries to be an action-packed war movie, it looks silly; when it tries for quiet tragedy, it fails to trigger any emotion. And most odiously, the story aims for moral grey areas but jumps all the way to sympathizing with a Nazi. Light is mostly just shallow, a surface-level World War II cliché.

Light takes place in 1944, as American forces are on the verge of liberating France from the Nazi occupation. Young, blind and on her own amid the horrors of war, Marie-Laure LeBlanc (newcomer Aria Mia Loberti, better than her material) determinedly broadcasts hopeful messages to her French and Allied compatriots on her radio from the seaside village of Saint-Malo as the Americans bomb. Elsewhere in the ruined town, German radio operator Werner Pfenner (Louis Hofmann) listens but doesn’t rat her out to his Nazi commanders. He develops affection for her and kills to protect her (you see, he’s the good Nazi, while the rest are cartoon villains).

Through a series of flashbacks, we learn that Marie and her father, Daniel (Mark Ruffalo), fled Paris when the Nazis invaded because Daniel was in charge of the precious stones at a Paris museum (or something, it’s never made clear). He hides most of the priceless gems, but takes one giant ‒ and rumoured to be cursed ‒ diamond with them. The pair make their way to Saint-Malo to shelter with Daniel’s uncle Etienne (Hugh Laurie), a World War I veteran housebound due to his post-traumatic stress disorder. But a Nazi gem hunter isn’t far behind. Werner gets a backstory, too: He’s an orphan with an uncanny ability to operate and repair radios who is eventually conscripted and trained to locate broadcast signals of Nazi enemies.

What Light lacks more than anything is subtlety. At one laughable moment, Etienne, a leader in the local French Resistance, shouts covert instructions for Marie to broadcast to the Allies while standing in the street. (The best spies shout their secrets in the middle of the road, right?) At another point, a character hugs a radio, the narrative’s symbol of freedom and hope. They speak English with the accents of their nationality, which are often distracting and verging on caricature. Ruffalo’s French accent is comedic at best and unintelligible at worst, but perhaps he should at least be commended for trying − Laurie sounds like Gregory House walked out of the hospital and into the south of France.

Light fails at its most fundamental level with Werner. The “One Good Nazi” trope has been done and redone in TV and films, and it is no longer a helpful storytelling tool; it just makes excuses for great evils. While morality is never black and white, we don’t need more stories that show shades of grey by casting a soft glow on Nazi soldiers.

Boluwatife Adesina is a media writer and the helmer of the Downtown Review page. He’s probably in a cinema near you.